How do you choose the right degree course, and where might it lead you? Will Hughes, BA (hons) History of Design graduate, describes his intellectual journey at the University of Brighton and introduces a new undergraduate degree that combines study of philosophy, politics and art.

I am Will Hughes. I come from Sussex in the UK, and am now approaching the end of my year studying for an MA in Cultural and Critical Theory, specializing in Aesthetics and Cultural Theory.

Early in 2010, I applied, via UCAS, for five different undergraduate degrees. My criterion for choosing between them was simple – that the courses they offered should be interesting. I accepted a place to study the BA in History of Design, Culture, and Society (now BA History of Design) at the University of Brighton.

I’d had no prior experience with design, and I hadn’t studied history since secondary school, but it seemed to fit the criterion. I felt that it could sustain my interest for the duration. It is one of the few major decisions that I have made because it was something that I wanted to do, rather than because of some immediate or future practical concern. In hindsight, it qualifies as one of my better decisions. Your decision about your higher education is too important to be based on what job you might want to do (or end up doing) in the rest of your life.

From the beginning, the content of the course was expansive. The courses on the degree looked at art, craft, and design – but mostly the latter two – from around the mid-eighteenth century to the present. From within this degree, I was able to develop my interests, which included politics in the focused sense (the implicit stratification of the arts, art as social engineering, etc.), which I pursued with regard to the nature of Modernism. I also developed an interest in politics in the generally accepted sense, which led me to investigate the design, poetry and prose of William Morris, the art and designs of Constructivism, and aspects of fascist architecture.

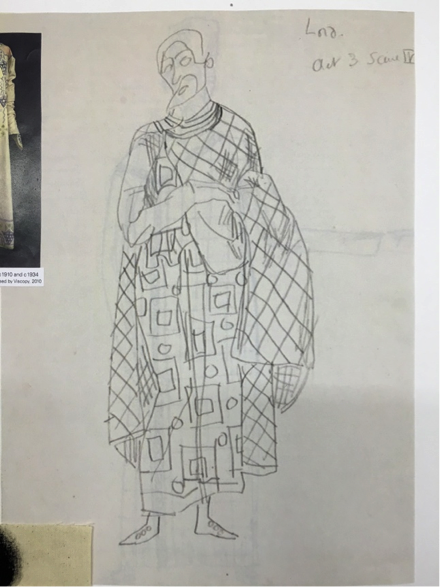

Will Hughes’ dissertation, on set design in 1930s Hollywood

In my third year, I completed a compulsory module on the reading of objects in conjunction with texts from other subject areas (mostly sociology, critical theory, and anthropology). This led me to the writings of Walter Benjamin, which I opted to explore in relation to industrial design and the historical avant garde. It is as a result of having studied on this course that I discovered that I wanted to study aesthetics and the philosophy of art.

After graduating, I enrolled on the Cultural and Critical Theory MA at Brighton, choosing the Aesthetics and Cultural Theory pathway. Though daunting at first, this was the work that I really wanted to do. I also followed the first term module ‘Foundations of Critical Theory’, which introduced me to continental philosophy. Keeping up with the reading was difficult. At least one new philosopher was introduced in the lectures each week. Between each lecture was the preparation for the seminar the following week.

Going from a state of ignorance to having a workable understanding of thinkers such as Kant and Hegel, each within a week, is difficult but I was nevertheless able to croak something intelligible in most of the small-group seminar discussions. Though difficult, this work was necessary to prepare me for the dissertation on which I am currently engaged – an identification of the deficiencies of Arthur Danto’s and Hegel’s teleological theories of art and of history.

The skills that I learned in my undergrad work on Art History are still applicable in Philosophy. I learned how to read texts critically, and how to craft an essay, and I didn’t accumulate too many bad habits in these areas. Ultimately, I want to organise my thoughts into a coherent view of the world. This is going to take some more time, some considerably more time. Consequently, I’m now thinking of doing a PhD.

Now Brighton is to have an undergraduate degree in precisely the area of my interests – the BA (Hons) Philosophy, Politics, Art. This degree will connect all of the interests that I had and have developed – art and representation, politics and political activism, philosophical reflection and theoretical engagement. My interest has always been in the connection between these critical moments of thought and action. Now this exists as a degree programme here in Brighton.