Jen Grasso is the Digital Content and Systems Co-Ordinator at the University of Brighton Design Archives and is also a graduate of the Curating Collections and Heritage master’s programme. In this blog post, she reflects on her career so far, and how the MA Curating informed her practice as a researcher and archives practitioner.

With a practice-based background in photography and over 10 years working in administration and recordkeeping, I enrolled in the MA Curating, Collections and Heritage programme in 2019 to see how I could apply my passion for the arts, culture and heritage with my accrued professional experience. I was interested in the theory and practice that founded modern-day collections and how heritage and culture was developed and supported in the UK. During my course I quickly became passionate about working with archives, an area I was lucky to explore during my student placement assessing the archive of photography non-profit organisation Photoworks.

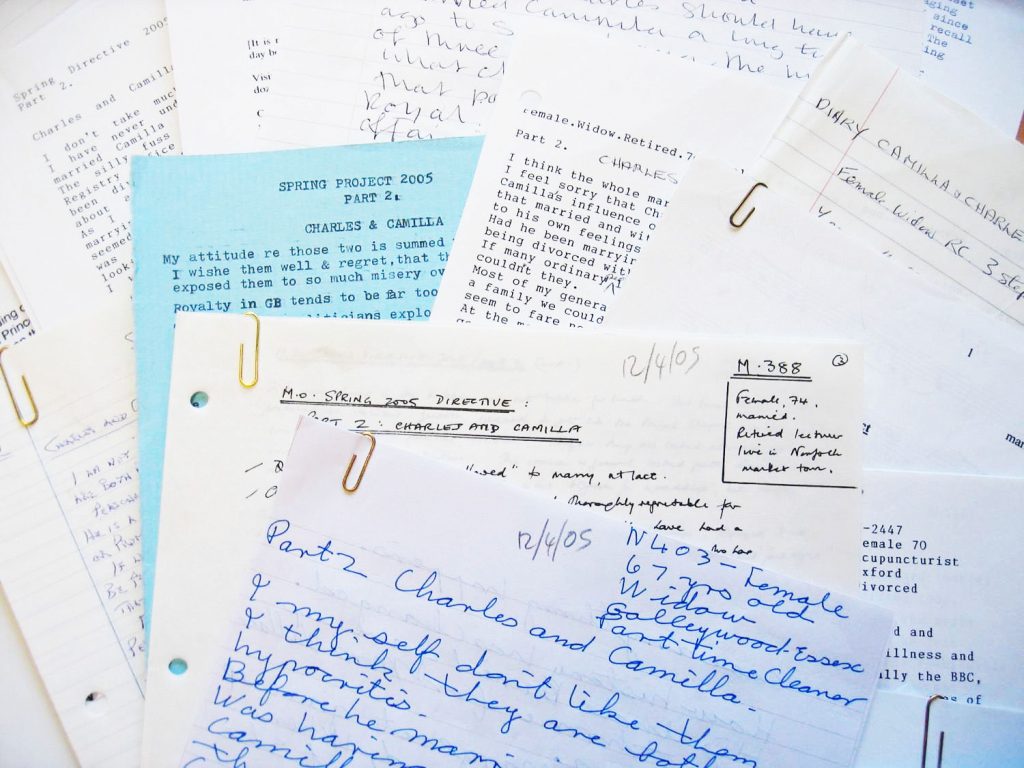

My placement was unfortunately cut short because of the Covid-19 pandemic and subsequent lockdown, but I continued to build on my passion for archives. I volunteered at the University of Sussex Special Collections on the National Heritage Lottery Funded-project Unlocking Our Sound Heritage (UOSH) that digitized sound recordings for the British Library’s Sound and Moving Image catalogue (SAMI). My main task was to listen to oral histories to flag sensitivity issues and create a summary for the catalogue. I listened to members of the Windrush generation talk about their first impressions of the UK; people’s experiences living through the Blitz; the recipients of the first social housing development in Southhampton, as well as different union members talk about the effects of industrial action. It was here I gained an appreciation for oral histories and how they can be used to document different communities.

Inspired by the UOSH project and the dissertation research I undertook during my master’s degree, which focused on polyvocal narratives and how they are expressed through photography, I began a community archive project documenting the role of the photobooth technician. This was also inspired by the postgraduate course in Archival Studies at the University of Dundee which I enrolled in following my master’s at Brighton. A technician myself since 2015, the Photobooth Technicians Project is an ongoing project that documents the history of the profession since its inception in 1925, in particular, the grassroots community that has arisen throughout the 21st century. It consists of semi-structured oral and written interviews combined with test strips from each technician, which is the main way to assess the status of one’s photobooth. I’m lucky to be able to share this project at the upcoming Photographic History Research Centre’s Annual Conference, The Photographer’s Assistants, at DeMontfort University in June.

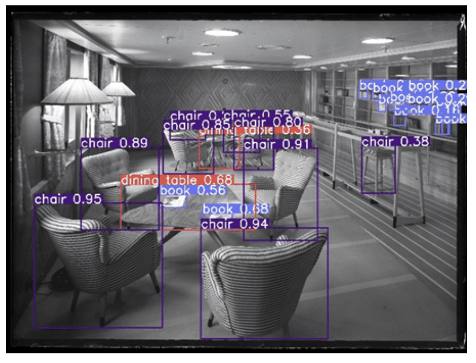

In 2022, I was hired as the Digital Content and Systems Co-Ordinator at the University of Brighton Design Archives. My work and research in the Design Archives focuses on the intersection between analogue and digital technologies and how technology can be used to democratize heritage. Part of this research involves an ongoing project working with Dr Karina Rodriguez Echavarria and colleagues in the School of Architecture, Technology and Engineering looking at how Machine Learning and AI can make collections more accessible.

Detail of the results of Santander-funded student placement applying machine learning to the discovery of the Design Archive’s collections. Original image © Design Council Archive, University of Brighton Design Archives.

I am also responsible for the digital generation, dissemination, and preservation of records at the Design Archives, and am part of a team that cares for, and makes accessible, records relating to graphic and industrial design from the mid-20th century, a wonderful resource I’m incredibly fortunate to work with. This role allows me to do what I’m passionate about, working directly with collections helping make them accessible, and also brings me back to the University of Brighton, a community that inspired me throughout my master’s degree and one I am now proud to be part of.