Graduating BA (hons) Visual Culture student, Kate Wildblood, reflects on the ways in which her personal, professional and academic interests intertwined in her dissertation, soon to be exhibited as part of Brighton Pride 2013.

Having spent most of my professional career either DJing within or writing about LGBT cultural and social life, when I became a mature student at Brighton University in 2010 it was perhaps destined that I would bring something queer to my Visual Culture degree. As they say, you can take the girl out of the disco, but you can’t take the disco out of the girl. My dissertation topic, Strike A Pose, There’s Something To It: Imagery in gay clubbing 1989-2013 examined the event flyer designs of Club Shame, Trade and Wild Fruit, showing how they reflected the 1970s Gay Liberation movement along with the challenges of the 1980s and early 1990s when HIV and AIDS dominated the public, political and media perceptions and portrayals of gay men.

By exploring Roland Barthes’ semiotic theory of myth, my research revealed how the flyer designers Mark Wardel (a.k.a. Trademark), B_Art, Pete Hayward and Paul Kemp created new meanings by reappropriating cultural iconography and signifiers, gay or straight – be they Oscar Wilde, Grace Jones, Aubrey Beardsley, Alice In Wonderland, Metropolis, Tom of Finland or Herb Ritts – to deliver images that challenge heterosexual ideals of masculinity.

In creating new images or subverting existing images for their own ends, gay flyer designers signified certain meanings, rooted in historical context, that connect the viewer to a particular aspect of gay culture, be they childhood memories, icons, subcultures or ideals of gay male beauty. By visually representing my research through the collages Trading Poses and Fruity Benders, I too reappropriated the images of gay clubbing to create further layers of meaning. Having spent so long surrounded by gay clubbing imagery I was keen to strike new poses with the material and to represent the rich queer history we have all played a part in developing. If you will excuse the puns, I wanted to Trade in the glorious Fruit-iness of it all.

I’m genuinely delighted that my two collages will feature in the Icons exhibition as part of Brighton’s new LGBT arts festival during the Pride events of 2013, and am honoured that my work will sit alongside artists including Keith Haring and Mark Vessey. The purpose of Pride, for me, has always been more than a party; it’s about celebrating the people of Brighton and our shared pride in our city. The Icons exhibition is a perfect reflection of that pride and a showcase for the artistic achievements of our seaside city. As so many of the images I used in Trading Poses and Fruity Benders originate from Brighton’s gay clubbing scene, it feels like they are coming home.

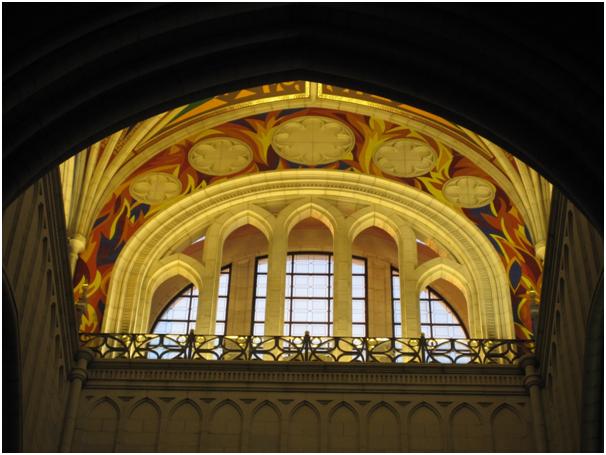

The Icons Exhibition is at Brighton Jubilee Library, Jubilee Square, Brighton until 1 August 2013. For further information on the event, please see the Facebook page:

https://www.facebook.com/events/153509038156320/

For more information about Kate Wildblood’s writing and research, see her blog: