Lisa Hinkins, MA Curating Collection and Heritage student, Brighton Museum and Gallery Explainer and artist, describes her input into a recent inclusive museum project.

The British Gypsy could be viewed as the stranger within, or as German sociologist Georg Simmel has put it, a ‘stranger in society from elsewhere’.[1] As a people who settled among other inhabitants, they have frequently been treated with suspicion and ignorance as they have been represented an exotic other that was difficult for many to understand.

Fig. 1. ‘Gipsy Fortune Telling Machine’, Royal Pavilion & Museums Collection.

Queer the Pier exhibition, Brighton Museum & Art Gallery. Photograph by Lisa Hinkins.

To address such ignorance the Queer the Pier (QTP) curatorial team wanted to utilise Brighton Museum & Art Gallery’s ‘Gipsy Fortune Telling Machine’ in their 2020 exhibition in the Museum’s Spotlight Gallery. As the Community Curator leading research and content for queer Roma inclusion, I collaborated with internationally-acclaimed Roma artist Delaine Le Bas, academic Dr Lucie Fremlova, LGBTIQ+ artists and workshop participants. Applying the theoretical framework of intersectionality – an understanding of the interrelationships between queer, Roma, Gypsy and Traveller communities – the participants created responses that challenge stereotypes and discrimination across these interconnected social categories.

I had the privilege to work on this project due to my own Romany heritage. My great-grandmother, Rhoda Wells [1897-1982], was a Romany Gypsy living in the New Forest, Hampshire. She met and eventually married my great-grandfather, Ralph Cuttriss Hinkins [1882-1952], when he and his father, my great-great-grandfather, Francis Robert ‘Frank’ Hinkins [1852-1934] befriended the Gypsy families. They spent many years periodically travelling with the Gypsies across the South of England. Many of the Hinkins clan were appalled by Frank and Ralph. It resulted in a distancing within family circles. Frank was a photographer and illustrator. In 1915, father and son published the book Romany Life: experienced and observed during many years of friendly intercourse with the Gypsies under the nom de plume Frank Cuttris. This book is still available, published by Echo Library. The Keep, Sussex’s historical repository, holds three lantern slides attributed to Frank, all c.1915, of portraits of travelling people.

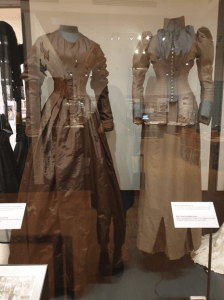

Decolonisation of objects in museums is imperative to inclusion. The LGBTIQ+ Roma, Gypsy and Traveller workshop collaboration sought to re-interpret the museum’s problematic Victorian ‘Gipsy Fortune Telling Machine’ (Fig.1). The object perpetuated a stereotype of Roma culture through the style of the human figure and through the misspelling of ‘Gipsy’ with an ‘i’ not a ‘y’. Reaching out to a continually-persecuted community, participants were welcomed into a safe space within the museum to produce drawn and written responses to the machine. A theme emerged with colourful images reflecting the Romani flag, the Rainbow flag and the use of positive language. Romani, the Roma language, has filtered through Cockney English and the queer subcultural language of Polari. Familiar words clobber (clothes), minge (vagina) and chavi (child/friend, now used as a derogatory term) originate from Romani, Cant or Argot languages.

Fig. 2. Fortune Telling Card by Delaine Le Bas. Queer the Pier exhibition. Brighton Museum & Art Gallery.

Photograph by Lisa Hinkins.

Developing ideas from the workshop, Delaine Le Bas (Fig. 2) created beautiful contemporary fortune cards with positive messages (£1 in the slot, a card is yours). In her words, ‘Fortune Telling is an intimate form of communication between people; it requires close contact physically and mentally in its true form.’ She continues, ‘for me in particular coming from such a demonised community I refuse to respond in a negative way.’

I edited the accompanying free zine that addresses stereotypes. It includes the following statement: “Gypsiness” is a term to describe the phenomenon of dissociation where over time Gypsy identity becomes abstracted and separated from the people themselves. Through images and literature, the dominant culture dictates the representation of a marginal group, in this case Gypsies. Stereotypes of Gypsy women have been perpetuated by figures such as Vita Sackville-West, who invented Romany ancestry for herself on her Spanish side of her family to explain her ‘bohemian behaviour’ (lesbian lovers).

Dr Lucie Fremlova’s postdoctoral collaboration with LGBTIQ+ Roma Artists has produced powerful images that break down and challenge the dominant representation of queer Roma people. Photographs created during a one-week workshop in Brighton were printed in the zine. An image of one of the Roma artists by the Palace Pier’s current ‘Zoltar Fortune Telling Machine’ accompanies the text for the Victorian machine. It is a powerful reminder that stereotypes are still interlaced with contemporary arcade amusements.

Delaine Le Bas pays tribute in the zine to her Uncle Eddie who moved to Brighton in the mid-1960s with his partner Peter. She acknowledges that their lives had not been easy being Romani and gay, but Delaine states that Eddie and Peter taught her the importance of being yourself and that love should be unconditional.

City-based organisation Friends, Families and Travellers is a leading national charity that works on behalf of all Gypsies, Roma and Travellers. They provided support and contacts for this project. This led to contact with Roma poet Lois Brookes-Jones who beautifully weaved Romani and English words into a poem expressing lesbian desire especially for the zine.

It is my sincere hope that this project engagement with LGBTIQ+ Roma, Gypsies and Travellers will help counter suspicion and ignorance towards ‘strangers within’. Brighton museum staff were fantastically supportive in encouraging an ignored community through its doors. A final thought: is it not ironic that a people so rich in its own creative arts, music and culture has never been fully appreciated within the institutions that claim to be custodians of our material culture? Perhaps we have an opportunity now to address that.

[1] Kalwant Bhopal and Martin Myers, Insiders, Outsiders and Others: Gypsies and Identity (Hertfordshire: University of Hertfordshire Press, 2008).