BA (Hons) Museum and Heritage Studies graduate (2017) Lindsay Lawrence on working at Michelham Priory

When I began studying for my degree in Museum and Heritage Studies at University of Brighton I had been working as a nursery practitioner in a children’s nursery for seven years. I was growing tired of the job and had started volunteering at a local heritage site, Michelham Priory. I helped in their Education Department, teaching school children about history in an interactive way, in a beautiful environment.

I knew I wanted to pursue a career in the heritage sector, which is notoriously hard to get into, so I gave up my job and decided to get some qualifications. I was lucky because through volunteering and showing my commitment to the Priory I had become part of the team and they offered me casual hours to help me get through university. Being a single mum with two children, going to university at the age of 35 was not an easy thing to do, but the staff and other students were really supportive.

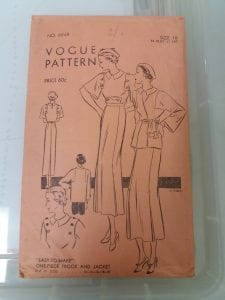

As I worked my way through my course so much changed. Gradually I saw I was basing a lot of my coursework around the Priory, which helped me get to know the history of the site better, but the university work was also showing me how to look at things around me. One of our modules was ‘Interpreting Objects’, this was fantastic, it showed us how to look beyond the object you have in front of you and to think about histories that object has been involved with. This has been invaluable to me in my work, for a variety of reasons. The trips we went on at university also contributed to making me look at things differently: we talked about how museums work, how they are constructed to lead visitors around a particular route so they view exhibitions in the way that is intended. We also talked a lot about what worked (or not) in museums we visited. This made me look at Michelham in a new way; what did I want to highlight, what did I want to make sure visitors paid attention to? I fed information about what I was learning back to the Property Manager, who was supportive in every aspect of my learning. Towards the end of the course I had taken over running the gift shop and helping with a few weddings. I also started helping to market the Priory on social media. By discussing museums and heritage properties at university it helped me think about what potential visitors would want to see.

My manager was keen for me to put into practice what I had learnt at university, tasking me with revamping our Rope Museum and making it a more practical visitor-friendly area of the site. This went well and the room is now much brighter, laid out to make sense of the displays, with much nicer descriptive labels.

After this I asked for a new project: I wanted to create a secondhand bookshop to raise more money for the Priory. The confidence I had gained at university encouraged me to push my ideas forward! I was given the go ahead and I worked with three other staff members to decorate and renovate our old nature room into a beautiful bookshop. This has gone so well that the money raised has paid for the Priory buildings to be 3D scanned, to become an interactive tool for visitors who can’t make it upstairs in the buildings, ensuring improved access for all.

For my dissertation I decided, yet again, to incorporate the Priory and write about my favourite era there: World War Two. I learnt a massive amount about the Priory during this time in my research, which has then enabled me to be able to talk to visitors in detail about this period. I have had many requests from volunteers to read my dissertation, which is helping to share that knowledge. The research skills I learnt at University have come in handy recently, as a family that used to live at the Priory in the 1950s came to visit. I interviewed them and it gave us all a real insight into the Priory as a family home. One part of my job I really enjoy is taking photographs around the site to advertise events, create interest in the site on social media and to create items to sell in the shop.

After I finished university I was taken on full-time as Visitor Services and Retail Supervisor. I am now in charge of retail on the site, ensuring the shop is presented beautifully, buying stock and managing volunteers, I also work in the ticket office and I organise a lot of the events such as Wildlife Wednesday, Homefront Weekend, Archaeology Day and I have created two new events so far: Superhero Day and Christmas in the Courtyard.

I absolutely love my job and I adore the Priory. I am given lots of responsibility and I am now part of the Duty Manager team. Every day is different, which is what I enjoy: most recently I have been filming with ITV and a US production company. If you had told me four years ago I would be in this position I would never have believed it. Hard work, a supportive manager and senior staff within the Society and an incredible three-year experience at university have helped me achieve my goals. Going to university was the best decision I could have made; the knowledge I have gained will stick with me and the support from the tutors was invaluable. I was given a piece of advice a few years ago from an ex colleague “Never stop learning, always have a go at everything, that will take you far”. It proved right for me, hard work, enthusiasm and commitment is what you need in this industry.