BA Fashion and Dress History student Caroleen Molenaar on a visit to the Fashion History Museum in Cambridge, Ontario

Figure 1: Exterior of the Fashion History Museum, Cambridge, Ontario. Photograph taken by the author. June 29th 2018.

Since beginning my Fashion and Dress History BA, I have made it my goal to visit the Fashion History Museum in Cambridge, Ontario every time I go home to Canada for the summer. The Museum was initially founded in 2004 by curator Jonathan Walford, formally an assistant curator at the Bata Shoe Museum in Toronto, and his partner Kenn Norman. Initially, the Museum had no permanent space to display objects from their collection of over 10,000 garments but in 2015 the Museum found its permanent home in Cambridge at the site of a former post office (Fig 1). Since its inception at the former post office, the Museum has successfully displayed different temporary exhibitions each year such as 2016’s To Meet the Queen: What to Wear in the Presence of Royalty, and A Canadian Fashion Story: Pat McDonagh 1967–2014; and 2017’s Fashioning Canada from 1867 and Dior: 1947-1962.

This year Walford put together an exhibition entitled 101 Tales of Fashion, which displays a very eclectic selection of objects from the collection. These range from an early eighteenth century French court male waistcoat, to a pair of 1984 Chinese beaded shoes. Despite the eclectic object and garment choices, as the exhibition title suggests, all of these objects are united not by their appearance but by the “interesting stories, tales, myths, & gossip” they tell to audiences.

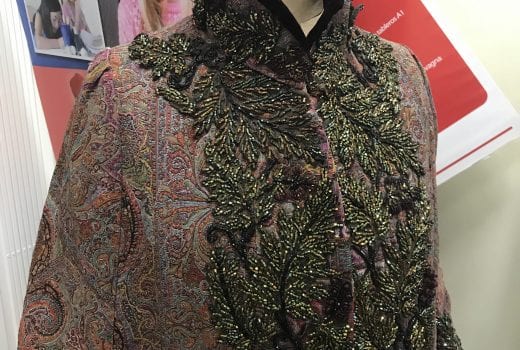

Figure 2: Christian Dior for Holt Renfrew. Afternoon Dress. 1954. Silk and taffeta. Montreal, Canada. Photograph taken by the author. June 29th 2018.

There were several objects that stood out to me throughout the exhibition and, coincidentally, they were all Canadian-made or designed. The first is the historical story of an afternoon dress designed by Christian Dior, but made in Montréal for the Canadian fashion retailer store Holt Renfrew in 1954 (Fig 2). Within Canada, Holt Renfrew is widely known as a high-end, expensive fashion retail store which originated in Montreal, but currently has nine stores across Canada. In 1951, four years after Dior launched his New Look, Alvin J. Walker, president of Holt Renfrew, established a deal with Dior exclusively to represent and sell both Dior’s Paris and New York fashion lines in Canada.[i] This deal also led to Dior designs, such as this dress, being made locally in Canada. A Dior work room was set up in Montreal, which allowed rich Canadian customers a cheaper alternative to buy Dior, as they did not have to travel overseas or pay import duties.[ii]

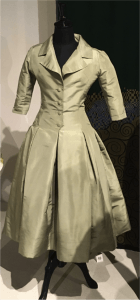

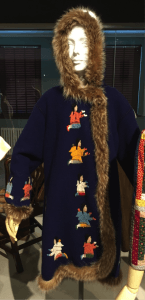

Figure 3: Alnaluaq Totalik. Parka. Felt and wool, trimmed with racoon. c.1980. Taloyoak, Canada. Photograph taken by the author. June 29th 2018.

The second object is a parka made in 1980 by Canadian designer Alnaluaq Totalik in Taloyoak, Nunavut, Canada — though at the time of its making it was known as Spence Bay, Northwest Territories (Fig 3). Due to the lack of sunlight and extreme cold throughout parts of the year in northern Canada, the parka has become an essential part of the First Nations’ wardrobe. It identifies the wearer, through use of colour and design, and protects them from the cold with the extended torso length, fur-edged hood and front closure. There are very limited secondary sources for the history of Taloyoak’s designs, but this could prove to be an interesting area for future research.

The final object is a pair of silver leather platform boots made by John Master in 1974 in Toronto, Ontario (Fig 4). These boots tell the story of how Master became “Canada’s disco diva answer to English rock ‘n’ roll cobbler Terry de Havilland.”[iii] After immigrating to Canada from Greece in 1970, Master opened a shoe shop in downtown Toronto and quickly caught on to the hype around platform shoes and boots. This fashion trend was permeating through the youth, led by bands such as AC/DC and Black Sabbath. At the height of the platform footwear craze, it is reported that Master sold over 300 pairs of footwear per week. When the craze died down in the late 1970s, Master changed his shoe output to focus on cowboy boots creating a very contrasting clientele; he died in 1996.

Figure 4: John Masters. Platform boots. 1974. Silver and leather. Toronto, Canada. Photograph taken by the author

From these three examples, one can see the eclectic range of objects in this exhibition, but also the interesting stories that all of these objects tell. Despite the Fashion History Museum’s small size, it provides a promising location in southern Ontario to educate and display fashion and its history.

Curator Jonathan Walford also has a blog that is updated weekly with interesting stories and objects about fashion.

[i]Alexandra Palmer, Couture and Commerce: The Transatlantic Fashion Trade in the 1950s(University of British Columbia: Vancouver, 2001) 117.

[ii]Palmer, Couture and Commerce, 119-120.

[iii]Nathalie Atkinson, “Stardust Memories,”Globe and Mail.17 June 2017. Web. 19 July 2018, https://www.theglobeandmail.com/life/fashion-and-beauty/fashion/the-history-of-the-master-john-platformheel/article35284918/.