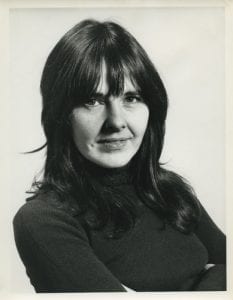

MA Curating Collections and Heritage alum Kila Galvin reflects on her work since graduating

When I began the MA Curating and Collections Heritage at the University of Brighton in autumn 2024, I knew I was interested in museums and collections, but I was still working out where I fit within the sector. What the course gave me, beyond practical skills and theoretical grounding, was the confidence to see learning and engagement as central to collections work rather than something that sits alongside it.

A pivotal part of the course was the opportunity to complete a placement at the University of Brighton Design Archives. This experience helped bridge the gap between academic study and professional practice, allowing me to work directly with collections while reflecting on the ethical and practical questions we explored in seminars. Handling archival material, contributing to cataloguing, and learning how records are structured for public and research access made me realise how much care goes into making collections meaningful. It also reinforced the idea that archives are active spaces of learning, not passive storage.

This understanding has continued to shape my professional experiences. At St George’s Bristol, where I work in visitor-facing roles, I have developed a strong awareness of audience experience and access within a live cultural venue. Being one of the first points of contact for visitors has shown me how welcome, clarity, and inclusivity shape how people engage with culture. Alongside this, my work with archival materials at St George’s has deepened my interest in how performance venues preserve their histories and create learning opportunities through documentation.

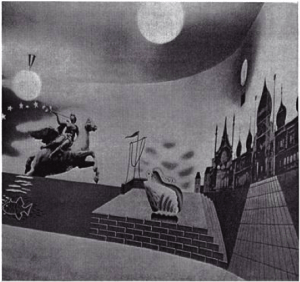

Volunteering at the University of Bristol Theatre Collection has further developed my skills in collections management. My role involves handling archival materials, cataloguing, and contributing to the organisation of records. Through this work, I have become increasingly aware that cataloguing is not a neutral task. Decisions about description, structure, and emphasis directly affect how visitors and academics encounter history. The course encouraged me to approach this work critically, with attention to representation and access.

I currently work with the Stradling Collection as a Learning and Engagement Officer, alongside a role in Marketing. This position has allowed me to combine collection knowledge with public engagement, developing activities and communications that make historic collections approachable and relevant to all audiences. Many of the questions raised during the MA about who collections are for and how people learn through objects now shape my daily practice.

Looking back, the Curating and Collections Heritage course gave me more than a pathway into the sector. It helped me understand how learning, engagement, and collections care are deeply interconnected. Across archives, performance venues, and historic collections, my work continues to be guided by the course’s emphasis on reflective practice, access, and meaningful public engagement. I would like to thank the lecturers on the Curating and Collecting Heritage course for their support and guidance throughout the MA, as well as my dissertation supervisor for their insight and encouragement. I am also very grateful to the University of Brighton Design Archives team for welcoming me during my placement and supporting my development, both professionally and personally.