PhD student Jayne Knight reflects upon her family photo collections, photo technologies and their relevance today. Jayne is researching the Kodak Collection at the National Science and Media Museum for her PhD.

The family photography collection of my paternal grandparents has been a source of intrigue and inspiration for much of my thinking about popular photography however, one decade of family photos in the form of 35mm colour slides from the 1960s, was until recently, the forgotten decade of family snaps.

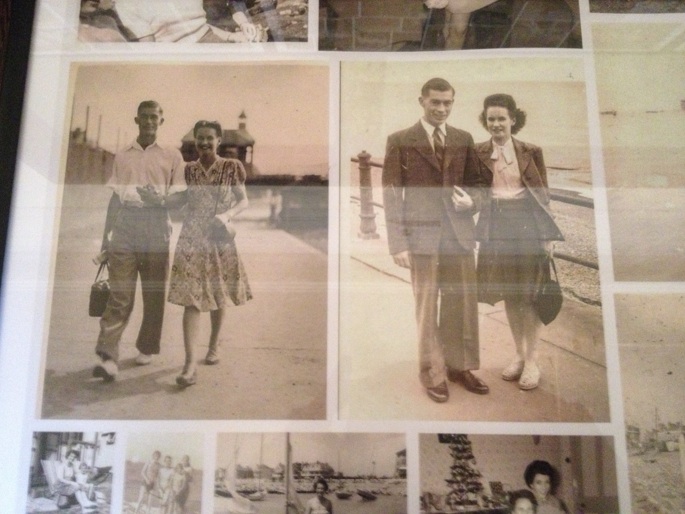

In the 1930s, my nan, in her teens, began capturing family life, events and holidays on her Kodak Brownie camera, snapshooting with my grandad until the 1990s with various cameras and creating many family photo albums, with Bonusprint being the last processing company of choice for my grandparents favoured 5×8 prints. Eventually my grandparents succumbed to the decline in popularity of analogue, never feeling the same enthusiasm for digital. For over seventy years, my grandparents snapshooting practices captured birthdays, Christmases, weddings, childhood and holidays, subjects shaped by companies like Kodak, Ilford and Boots whose guides, advertisements and packaging encouraged these events to be recorded with their products and services.

My family photos, characteristic of many other family photo collections take many different forms, reflecting the changes in technology and popularity of new products, services as well as ways of viewing. Studio photographs, assorted Kodak Brownie negatives and prints, real picture postcards, itinerant seaside photographs, 35mm negatives and prints, collages and albums represent some of these different types. Examining the seventy years of my family’s photos, identifiable photographic trends have seamlessly connected different decades of family life, except for one, the 35mm colour slide transparencies from the 1960s which were until recently detached and a forgotten part of the family collection.

Colour transparencies, small card or plastic frames measuring 2×2 inches holding a 35mm colour positive image, were mostly viewed through photographic apparatus such as pocket viewers and projectors. Taken on the family’s Halina 35x camera, and often using the popular Kodachrome film, the existence of the colour slides was known to my immediate family, stored under the bed for twenty years in the plastic containers of processing companies. Last year, blowing off the dust I decided to take a closer look at the 35mm slides, seeking to find images of my dad as a child which were notably absent from the well-kept, and largely chronological, photographic family collection that resides with my grandad. Not only did I rediscover a decade of family photos, but I also became fascinated with 35mm colour slides and the experience of viewing them.

3. My nan, on holiday in Dymchurch c.1965. 35mm slide. Personal collection 4. My dad and his many toys, c.1966. 35mm slide. Personal collection.

Spanning the 1960s, the Kodachrome colour snapshots still impress through the vintage Argus PreViewer that had been gathering dust alongside the slides, acting as a window on a decade that embraced bold colourful prints and family fun. Deckchairs, garden toys and patterned dresses, like the slides and viewing apparatus themselves, provide a snapshot of 1960s lifestyle and design.

In a decade that saw a spike in photographic activity, due to the arrival of my dad, 380 35mm colour slides and hundreds of feet of cinefilm captured his childhood. Separated from the rest of the family photo collection, the 35mm slides (and cinefilm) had until now been largely side-lined due to their form. Considered by my family as trickier to view, susceptible to dust, awkward to store and reliant on other ageing apparatus, they have been considered an obsolete media. For me, viewing slides through a pocket viewer or setting up a projector is as interesting as the image subject, reminiscent of handheld three-dimensional stereo-viewers and shared viewing experiences of magic lantern shows.

As the 35mm slides have shown me, some types of family photography, such as photo albums, have remained at the forefront of reminiscent viewing experiences with the more apparatus dependent 35mm slide viewing fading into the background, despite their shared subjects. The 35mm colour slides have now been scanned and printed as more conventional 4×6 prints for other family members who had never seen them, but for me, the act of viewing through the original 1960s projection is as much a part of the forgotten decade as the images themselves and will remain a ritualistic viewing experience when revisiting the family snaps in the future.