Elena Field, Third Year BA Fashion and Dress History student shares her research and reflections on how social media expands dress history.

Bernadette Banner. 1890’s Ball Gown Instagram post. 5 October 2020. Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/bernadettebanner/

In Doing Research in Fashion and Dress: An Introduction to Qualitative Methods, Yuniya Kawamura states that ‘it is the responsibility of fashion/dress scholars to elevate the importance as well as the interests of the topic in academia.’ Through my own personal experience, I have seen that one way this is being done is through the circulation of research on social media platforms, which has in turn created global dress history communities. Amanda Sikarskie, in her Digital Research Methods in Fashion and Textile Studies, has termed these communities as ‘the crowd,’ claiming that members are able to help each other through sharing knowledge. Social media can also aid academics when conducting research, as hashtags may link them to different primary and secondary sources relevant to their research that they might have been unaware of. Online events and discussions additionally provide a platform on which dress historians and museums can collaborate. This is especially important for museums in the time of Covid-19, as they are able to directly engage with visitors.

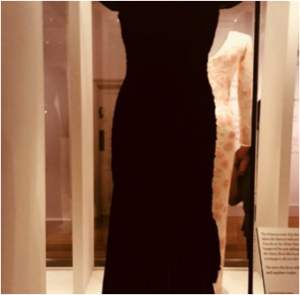

I am particularly interested in how YouTube offers a means for historical dressmakers to contribute to dress history studies. To give an example, the Costuber and Dress Historian Bernadette Banner uses her YouTube account to post videos on a variety of dress history related topics, from pointing out inaccurate costumes in television series and movies to making her own historical outfits, such as her video on making an 1890s ball gown. Hilary Davidson, in her essay The Embodied Turn: Making and Remaking Dress as an Academic Practice, argues that making historical dress is a form of research, in which the dress maker can develop a deeper understanding of a garment’s construction and embody the seamstress who would have made the original piece. Therefore, it is my opinion that Costubers like Banner are actively contributing to academic research in the field of the dress history, as well as sharing it with the wider public through digital platforms.

Cheyney McKnight. Not Your Momma’s History Instagram Post. 14 October 2020. Instagram. https://www.instagram.com/notyourmommashistory/

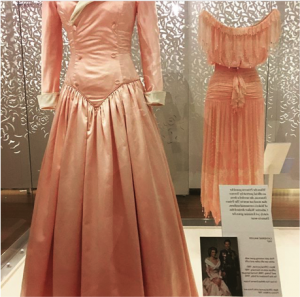

The combination of social media and historical dress, especially in the case of donning historical clothing for re-enactment purposes, is also a way to decolonise history. One predominant example of this is Historian Cheyney McKnight, who uses her social media account and company, Not Your Momma’s History, to navigate her discussion on black history. An example of her work is the project #slaverymadeplain, a series of performance art, where McKnight dressed as an enslaved woman in public in order to prompt a discussion with passers-by into how the effects of slavery are still relevant in American politics and African-American lives. A discussion on this subject is continued on her YouTube account where, through her use of historical costume and re-enactment, she has created content on such topics as her life as a black re-enactor, harassment and sexual assault experienced by African-Americans and slavery.

Though there is always a question over the historical accuracy of the content published on social media, it can be deduced that social media should and is being used to expand the field of dress history and its academic standing, concurring with Yuniya Kawamura’s statement.