BA (Hons) History of Design, Culture and Society grad 2015 Veronika Zeleznaja reflects on life, work and study since graduating from Brighton

I completed a BA (Hons) in History of Design, Culture and Society at the University of Brighton in 2015 and just a few months ago I graduated from University of the Arts London, Central Saint Martins’ Culture, Criticism and Curation postgraduate programme. Following my MA, I have relocated to Los Angeles, California.

At Brighton, my studies encouraged an interdisciplinary approach to form and culture. I applied a range of critical approaches to the study of the design and consumption of objects, from one-off pieces to everyday goods, starting in the mid-eighteenth century and running through to the present day. My BA dissertation, on mid-century American modernism in Forbidden Planet, explored how design is intimately bound up with the cultural, social and economic norms of its day. The dissertation looked at the connection between design, architecture and media, and how that science fiction film, and others of its day, reflected increased American leadership in the 1950s and promoted and propagandized its values and lifestyle. It drew on my fascination with the Californian Case Study Houses, a post-World War II modernist residential architecture project, discovered through the Making the Modern Home: Design, Domesticity and Discourse 1870 to the present module (taught by Jeremy Aynsley). It evolved beyond an academic interest when I visited the Eames House in California (Fig 1.), and relates to my recent move to Los Angeles.

After my studies at Brighton, I took a gap year and returned to my home country, Lithuania, and undertook an internship in the LIMIS (Lithuanian Integral Museum Information System) department at the Lithuanian Art Museum, helping to create a common digital archive of museum collections across Lithuania. I was responsible for digitising, managing and editing images to be published online, proofreading and copy-editing as well as working with the LIMIS database.

I did not take the usual route to jobs and internships through applications and posted vacancies online. Instead, I showed up in person at the institution of my interest and offered my candidature directly. This approach not only resulted in the offer of a position but also led to some useful contacts, who have offered sound advice along the way. Furthermore, this internship gave me an opportunity to engage with issues and strategies in presenting cultural heritage objects, and furthered my interest in how public relations relates to curation, presentation, and public engagement in art. It resulted in enrolment to the Public Relations MA programme at the University of the Arts London. After the first term, I realised that my interest in the issues surrounding the presentation of culture in public and social spaces, in what I thought of as the PR corner of the art world, were not addressed in the curriculum. So I switched to the Culture, Criticism and Curation course at Central Saint Martins, aimed at candidates with an interest in research and its application in organising cultural events. The programme offered a critical and historical framework for engaging with the culture that I found resonated with me, due to strong theory foundations in my BA. This MA course emphasized a hands-on teaching method and was mainly structured on ‘live’ projects used as a testing-ground. Led by students but done in partnership with external organisations, these projects taught me how to collaborate effectively.

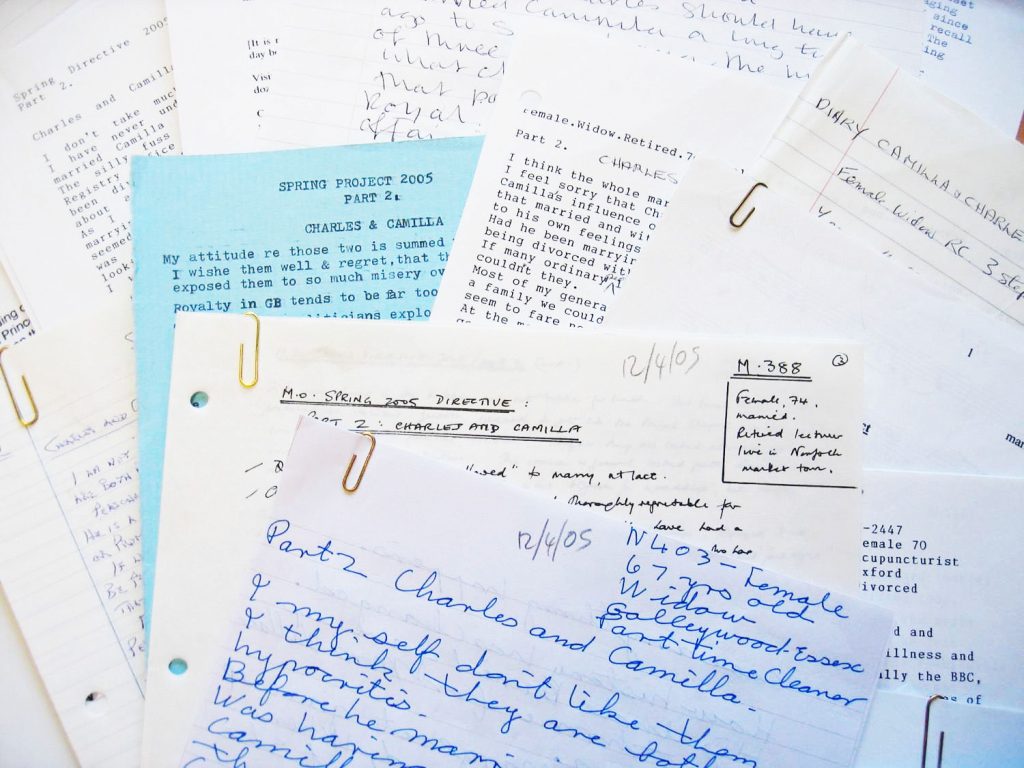

After putting up an archive-based group exhibition as one of the first assignments, for my final project I chose to address a series of seminars on art criticism within the MA programme and joined the editorial board of Unknown Quantities, an annual collaborative project developed by MA Culture, Criticism and Curation and MA Graphic Communication Design students. Our group created an experimental concept-based physical publication that set out to contribute to cultural criticism and communication design, bringing together contributions from the team and direct external commissions from artists, writers and practitioners (Figs 2 and 3).

For my MA thesis, I examined the interplay of political, economic, cultural, and social forces that triggered interest in Russian art abroad, specifically in London, as well as curatorial choices around national art for international export. The dissertation explored how museums and art institutions have developed their roles as elements of soft power, as sites able to produce a favourable image of a country, by functioning as platforms for cultural display and exchange.

Now I have relocated to America. Los Angeles has a thriving art scene and I hope to put both of my degrees to excellent use here.