Alice Power, first year student on the BA (hons) Museum and Heritage Studies degree pathway, completes the short series of blog posts resulting from a recent study trip to Madrid by examining the distinctive traditions of Spanish Catholic art.

As we stood outside the Almudena Cathedral in the heart of Madrid, I turned to my student colleagues and set them a challenge, asking: ‘How old do you think this building is?’ Here was a chance to put into practice what we’ve been learning in our first year History and of Art and Design lectures by looking at a building of which none of us had prior knowledge. The four of us looked carefully at the decoration that adorned the ornate exterior. It didn’t seem to fit clearly into any style or movement that we were familiar with. There were certainly Baroque influences, which complimented the neighbouring Palace nicely, but as a whole it looked too fresh to be from that period. Our collective brain power estimated that it probably dated from circa 1875. We weren’t far wrong. Construction started in 1879. However, due to despites over decor and the turbulent political conditions in Spain during the twentieth century, it wasn’t completed and consecrated until 1993.

Fig. 2. Exterior of Almudena catherdral taken from Calle Mayor , Madrid. Amy Lou Bishop. 13 February 2013.

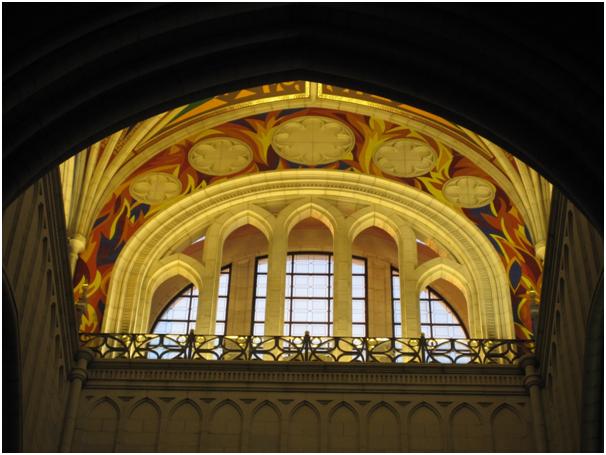

The interior was, somewhat unexpectedly, neo-gothic in style. Nevertheless, the bright whiteness of this still-young building gave it a very different atmosphere to the countless neo-gothic churches I’ve visited in the UK, Ireland and France. The ceiling decoration was very fluid and modern, marked with the bright colours that one often associates with Spanish imagery. We visited on Ash Wednesday, so the space was active with worshippers as well as tourists. Despite this, the space felt somehow bare. Due to its age, it isn’t cluttered with tombs and monuments. One of my fellow students mentioned that it felt more like an art gallery than a place of worship. With little uniformity in the scale and style of art displayed in each chapel, it was easy to view them as exhibits. As I had been educated in Catholic school, I’m fairly familiar with what each of the religious signs are meant to indicate, but here things weren’t so typical. Christian art, as a category, is vast and ever changing, yet within Catholicism, traditional styles and forms usually dominate.

Two years ago I visited a church called Parroquia Nuestra Señora de la Encarnación in Marbella. It was situated down a rather unassuming alleyway in the old quarter of the town. I found the style of the interior, however, to be completely overwhelming. Many of the statues were life-size, draped in velvet robes and featured real hair. Each one was richly decorated with gold. They were extreme examples of what I’d anticipated. The iconic, highly decorative images of Catholic saints produced in Spain and other Hispanic countries are globally recognised as distinct to their cultures. Hispanic-style images of the Virgin Mary are a staple of any tattooist’s repertoire and are also often recreated in kitsch novelty items. Examining the chapel of Ave Maria Purisima sin Pecado Concebida in Madrid’s Almudena Cathedral, however, challenged all my preconceived ideas about Catholic art in Spain. The chapel was focused on an oil painting of the Madonna. Instead of highlighting her holiness by covering her in regalia, this Madonna was depicted in white with her head exposed, carrying a light. The most striking aspect to me was how clearly youthful she was. The gospels say that Mary was in her early teens at the birth of Christ, yet in most of the art created in her image she is more like a doll than a child. The painting did exactly what religious art is supposed to do. It made me think. Although I’d heard the gospel passages countless times, I don’t think I’d really ever connected the stories to the condition of a modern day young mother. Above the painting was a stained glass window made up of strikingly modern angular shapes. This is something I’d often seen in Protestant churches, but never in a Catholic cathedral.

In many Western cultures, the presence of a cathedral is still an unofficial sign of city status. Yet, for centuries, Spain’s capital lacked an operational Catholic cathedral. As an outsider I found this peculiar. I’d always assumed that there was something almost innately Catholic about Spanish national culture. In reality, Spain’s religious identity is a result of a long standing power struggle between Jewish, Islamic, Protestant and Catholic traditions, as well as the amalgamation of many strong regional identities. Nonetheless, 92% of people living in Spain consider themselves Catholic although many infrequently attend church. In some regions, parishes broadcast masses on local television networks. Perhaps this explains the diversity of the art in their churches. While in the UK, we’re predominantly interested in preserving the past, in Spain religion is much more connected to the present. Not long after I returned from Madrid, a news story about a Catalan church that commissioned local graffiti artist to paint its dome was widely reported: www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-21529832. This shows that modernising trends are evident in churches all over Spain.

Ultimately, Madrid’s Almudena cathedral is not just a place of worship and tradition. It is a boast that Catholicism survived attempts by other faiths to become dominant. As a site that incorporates elements of the past and the present, as well as local and universal iconography, it’s also a showcase for the diversity of Spanish national history and culture.