Second year BA (hons) Fashion and Dress History students Amy Hodgson, Nicola Goodwin and Nicola Hayward describe their ‘once-in-a-lifetime’ insight into the historic dress collections of Paris.

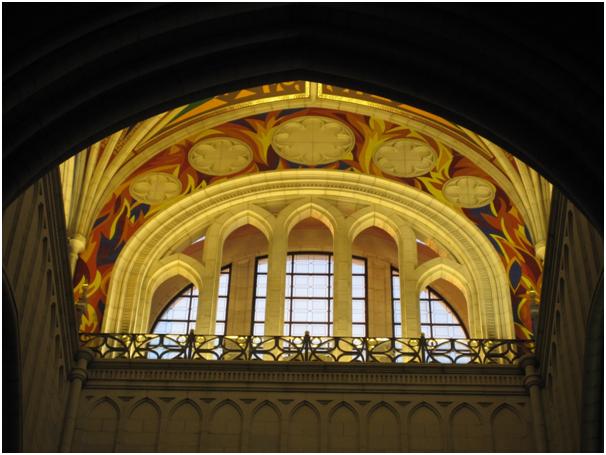

As part of our second year option, A Trip to Paris, we were given the chance to go on a five-day study visit to the culturally and historically rich French capital over Easter 2013. As student dress historians it was unfortunate that many of the permanent fashion museums and exhibitions were closed during our time there. However, the Musee Galliera had exhibits in various locations and venues around Paris. One of these was the Paris Haute Couture show at the Hotel de Ville, an enlightening and informative experience which showed not only examples of couture garments but also gave an insight into their elaborate and innovative design techniques. This show included many designers who are not household names, and provided a broad selection showcasing fashion throughout the eras to enthusiastic crowds of visitors. After witnessing this exhibition by the Galliera we were curious to understand the work that takes place to create such a vision.

Luckily we were given the rare opportunity to visit the Musee Galliera costume stores. Despite the renovations that were taking place, our tutor Dr. Charlotte Nicklas was able to arrange the trip through a colleague and curator who was working there. Under heavy security we began our tour of one of the largest dress collections and restoration facilities in Europe, featuring thousands of garments, photographs and historically significant records. Needless to say we were overcome with excitement at the prospect of being allowed to witness this fine collection.

Figure 1. View of the Restoration Room and early 20th Century Dancing Dress. Musee Galliera Store Rooms, 2013. Personal Photograph by the authors. April 22nd 2013.

Firstly, entering the conservation room, we were faced with an early twentieth century dancing dress being restored by expertly trained seamstresses and members of the highly regarded team of conservators. Every item is meticulously studied, conserved and catalogued before it is considered for the collection. The store rooms even feature a room dedicated to garment cleaning; steamers, hoovers and washing implements are used to make sure all garments are immaculate and at no risk of insect infestation.

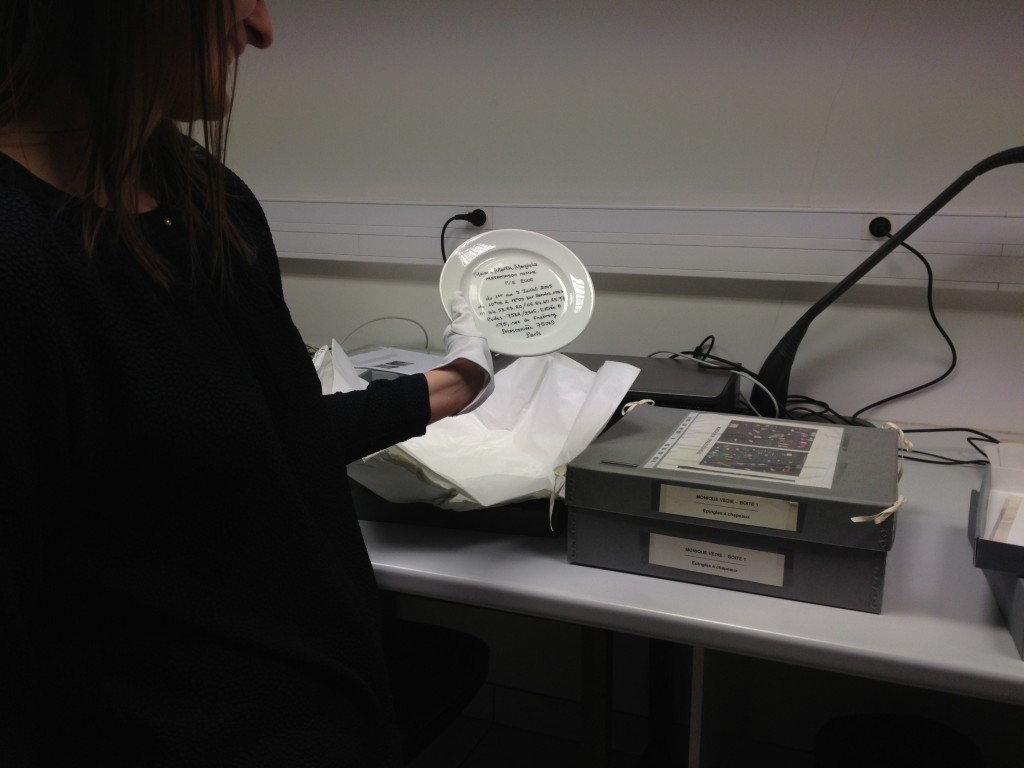

Figure 2. View of Martin Margiela 2006 Menswear Invitation. Musee Galliera Store Rooms, 2013. Personal photograph by the author. 22nd April 2013.

As well as garments, the museum also acquires significant documents, photographs, and accessories. All of these elements are essential to creating an understanding of the fashion industry throughout history. One of the examples we were able to see was a Martin Margiela 2006 Menswear show invitation, which offered a glimpse into the post-modern, conceptual fashion world, where the invitation is the first insight into the illusion and theme of the fashion show. The numerous records and photographs that are gathered by the Musee Galliera are easily overlooked, but are equally as important in understanding the culture, images and innovative work that surrounds, and are sometimes created by, many of these designers.

The next stage of the tour was the storerooms, where we were asked to wear shoe protectors to prevent outside germs entering the controlled space. The room is kept at a consistent temperature and monitored constantly. We were faced with rails upon rails, as far as the eye could see, all holding historically significant garments from a range of eras, and each holding their own stories. We were guided through a maze of storage containers. It was unlike anything any of us had ever seen or could have imagined, and was quite overwhelming in its scale.

Figure 3. View of a Worth 19th Century Opera Coat. Musee Galliera Store Rooms, 2013. Personal photography by the authors. April 22nd 2013.

We were shown three garments that had been chosen to represent their particular era, from the 19th century and early 20th century to the 1950s. All were excellent examples, embodying the style and design of the their time. A late 19th century Worth opera coat, for example, acted as a potent symbol of bourgeois decadence and the luxurious lifestyle that this social standing entailed. The second example we were shown was a 1920s dancing dress, adorned with rhinestones and velvet fringing, by an unknown designer. Again, this piece evocatively embodied the changing notions of femininity for which the 1920s are well known. It also exemplified the innovative design and skilled workmanship that is involved in creating such a heavily embellished garment. The third and final garment we were shown was a dress that was part of Yves Saint Laurent’s first collection for Dior in 1957/58. The dress echoes Dior’s New Look style, with hidden corseting and a full skirt, creating the recognisable 1950s fashionable silhouette. The monochrome floral print gave the dress a photomontage effect and the motif appeared quite modern because of these elements. This small selection provided a glimpse into the varied and impressive collection at Musee Galliera. The final room that we visited showcased the museum’s selection of mannequins and the workmanship that is put into displaying garments. Differing body shapes and changing attitudes towards the body must be taken into account, giving a historically authentic form for when the garments are exhibited.

Figure 4. View of 1920s heavily embellished dancing dress. Musee Galliera Store Rooms, 2013. Personal Photograph by the authors. April 22nd 2013.

Figure 5. View of Yves Saint Laurent for Dior 1957-1958 Couture Dress. Musee Galliera Store Rooms. Personal Photograph by the author. April 22nd 2013.

We were delighted to be offered the opportunity to have a once-in-a-lifetime insight into the inner workings of one of the most important and vast dress collections in Europe. Even though the garments that we saw were spectacular, to be given the chance to observe the conservation, organisation, display and management of the collection was truly insightful. All of these elements demonstrated the vast amount of work undertaken by the highly regarded team of specialists who understand the importance of building and maintaining this internationally important collection.

Figure 6. View of our Protective Footwear that must be worn whilst inside the Store Room. Musee Galliera Store Rooms, 2013. Personal photograph by the authors. April 22nd 2013.