Final year BA (Hons) Fashion and Dress History student Maria Purnell on working at the National Trust property, Standen House and Gardens.

Normally, balancing a degree with work is hard. However, having the opportunity to work for the National Trust as customer service assistant has allowed me to earn money, learn new skills and provided me with valuable knowledge, not only about the Trust’s purpose, but about the property itself.

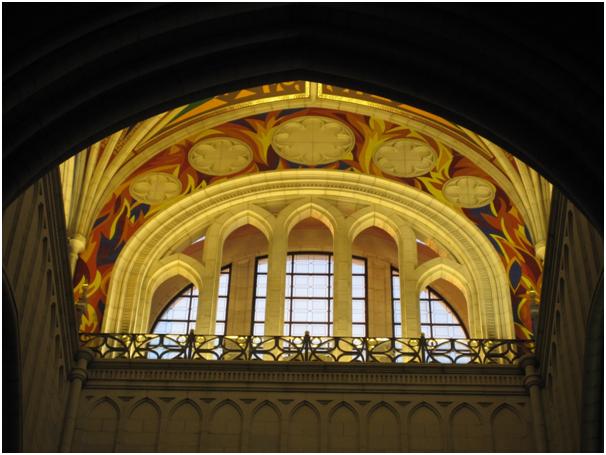

Standen House was owned by the Beale family, who lived in London but built Standen as a holiday home, for the much-appreciated clean country air away from the city. What makes this house so special to the Trust is that it is a perfect case study of the Arts and Crafts movement, designed by Philip Webb in collaboration with William Morris. Working at Standen however, isn’t your ‘average’ student job. Upon arrival before the visitors, it is astounding how peaceful and tranquil the gardens can be. The scenery is breathtaking; on a clear day on top of the hill you can see for miles around, overlooking the countless fields and trees. One of the best aspects of working at a country house is how close to nature one can be; on a quiet day one tends to see an abundance of wildlife such as rabbits, squirrels and robins, which are not particularly afraid of humans.

The majority of the time I work either in reception, scanning the memberships and helping provide information to visitors or, when particularly busy, down in the car park, helping everyone park sensibly and giving people information and directions. This Christmas 2017, however, I got given the opportunity and responsibility to oversee ‘Woodland Santa’, our property’s Christmas grotto. It was an incredible experience and a privilege to be able to take part in such an event. Management put their faith in my abilities to organise elves and make sure Santa had enough presents for the children. Luckily the event was a huge success, and the children and their parents were thrilled with the property and the organisation.

The knowledge I have gained so far during my time working with the National Trust has helped greatly towards my degree, when understanding art, design, domestic and social history of the period which Standen dates from. Studying a degree in fashion and dress, one has to take into account the significant events within a period that can influence art and design. Standen House and the National Trust have provided me with much knowledge about the creation of this country house and allowed me to pass this on to visitors. Although the job has helped contribute to my degree, I also think the degree has helped me to do my job. Fashion and Dress History has allowed me to gain confidence when talking and explaining theories and historical concepts to fellow students. I have adapted this skill to my job at Standen, by having the confidence to talk to the general public about the history of Standen and the social and cultural histories that it reflects.

Standen House and Garden is at West Hoathly Road, East Grinstead, West Sussex, RH19 4NE