Emma Bull, BA Fashion and Dress History, returns to her roots at the Welsh National Museum of History.

Deep in the heart of Cardiff, Wales, lies a museum seemingly frozen in time. St Fagan’s National Museum of History consists of original buildings ranging from the early 16th to the 20th century, excavated from around Wales and reconstructed at the site. St Fagan’s also contains separate galleries focusing on Welsh life, the stories of donated objects and their impact upon Welsh people and culture. Refurbished in a £30million redevelopment, these galleries reopened in late 2018. Being of Welsh origin and having visited the museum many times when growing up, I was intrigued to see how the main galleries had been revamped.

Now named Byw a bod… (Life is…), the main gallery space explores Welsh lives and memories. As the museum describes it, ‘We tell people’s stories through their own words – wherever possible – and through the objects they treasured […]. This gallery takes the ordinary stuff of all our lives and shows it to be extraordinary.’ The space is separated into three sections. The first focuses on work and heritage, the middle on leisure and the last, rather controversially for a museum targeted at all ages, on death and remembering those lost.

Fig 1. A young boy interacting with the original tractor exhibit overlooking the exterior farm views. St Fagan’s website. Colour Photograph. 2018.

Starting with the exhibit on gweithio (work), it was interesting to see how the curators have decided to show objects from separate walks of life. Upon the first wall are hung agricultural objects such as rakes, hoes and domestic household objects. They are identifiable by numbers, which can then be found on a large sign, interactive screens or information booklets. Having three ways in which to access information allows the visitor to explore the exhibition in the way that best suits them; the speaking screens allow for those with hearing and sight disabilities to also interact with the gallery. There is an original tractor that children can climb on, overlooking the exterior farm. Also featured are Laura Ashley factory woollen threads (Canolbarth, 1960s) and an original fish fryer (Cardiff, 1915). The idea of memory persisting through objects is prominent and the eclectic formation of the gallery feels personal. Being able to read anecdotes from families who donated the items develops visitor appreciation and provides value; the sometimes mundane object is made significant by its story.

This curatorial method is outlined by Swiss art curator Hans Ulrich Obrist in his 2014 book, Ways of Curating. He writes that when he interviewed Eric Hobsbawm [1917-2012], the historian described curating via memory as a ‘protest against forgetting’. Through this, he argued that recollection is a contact zone between the past, present and future. I believe this kind of memory-based curating was the aim of St Fagan’s, who attempt to bridge the gap between generations.

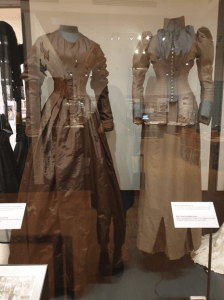

Fig 3/4. Examples of the Fashion displays with the Byw a bod… gallery. Author’s own images. 2 January 2020.

Continuing to the area about leisure in Wales, I was naturally drawn to the cabinet of clothing, dating from the 1870s to the 1950s. Although the garments on display were exceptionally beautiful, the cabinet itself was sadly lacking. The gallery was lit by strong LED lights that reflected on the cabinet making it difficult to see the true detail of the items. As the cabinet was not lit from the inside it was difficult to read the plastic labels unless at a certain angle. Although it is important to control lighting to not damage or discolour garments, being unable to view the pieces affects visitors’ enjoyment. As noted by conservator Garry Thompson in his 1978 book, The Museum Environment, works of art ‘will look better in some lighting situations […we should bend our efforts to finding the best possible’.

Fig 4. Examples of the Fashion displays with the Byw a bod… gallery. Author’s own images. 2 January 2020.

In addition to these shortcomings, garment labels were lacklustre. Although they provided some information about the origin of the items, they failed to describe the methods of construction, fabric or further context, making it difficult for somebody who did not know much about fashion history to gain deeper insight. Once again, this area provided a space in which children could interact, this time in the form of a dressing-up zone with recreation garments. There were some swimsuits displayed separately here that were easier to view.

Fig 5. Cast iron and etched glass carriage and premature birth coffin, c. mid-1800s. Author’s own image. 2 January 2020.

The gallery concludes with the idea of marw (death). There is a beautifully displayed carriage from the late 1800s and a premature death coffin made from cast iron and etched glass. The gallery does well in presenting death in a less morbid way than expected; instead its focus is predominantly that of remembrance, which works well to conclude the gallery theme of memory and remembering history.

Overall, despite a few issues with lighting and labels, the gallery presents unique and interesting stories and objects from around Wales. It presents its artefacts in a way that is inclusive of all ages and physical abilities. The galleries are easily accessible, interactive and well worth the visit.