MA History of Design and Material Culture student Chelsea Mountney describes how her current work with the historic dress collection at Worthing Museum draws upon the skills and ideas she developed during her MA, including the module ‘Caring for Collections and their Users’.

“Oh, my goodness” I screeched as I leaned in closer to smell this bodice from a woman’s black taffeta outfit from the 1910s, pictured above. “Can you smell that? What do you think that is?” I was informed by the ever-knowledgeable PhD student, Jo Lance, that the unusual smell was probably the scent of wood smoke that was lingering on the cloth, as homes were, of course, commonly heated with open fires.

This was my first afternoon volunteering at Worthing Museum and I had already been reminded of how crucial physical objects are in divulging history. My first task as a new volunteer was, in my eyes, possibly the best job in the entire world, to repack women’s costume for storage in their new dress archive. This kind of work, as many fashion historians will also agree, is a blissful opportunity to access and handle many items.

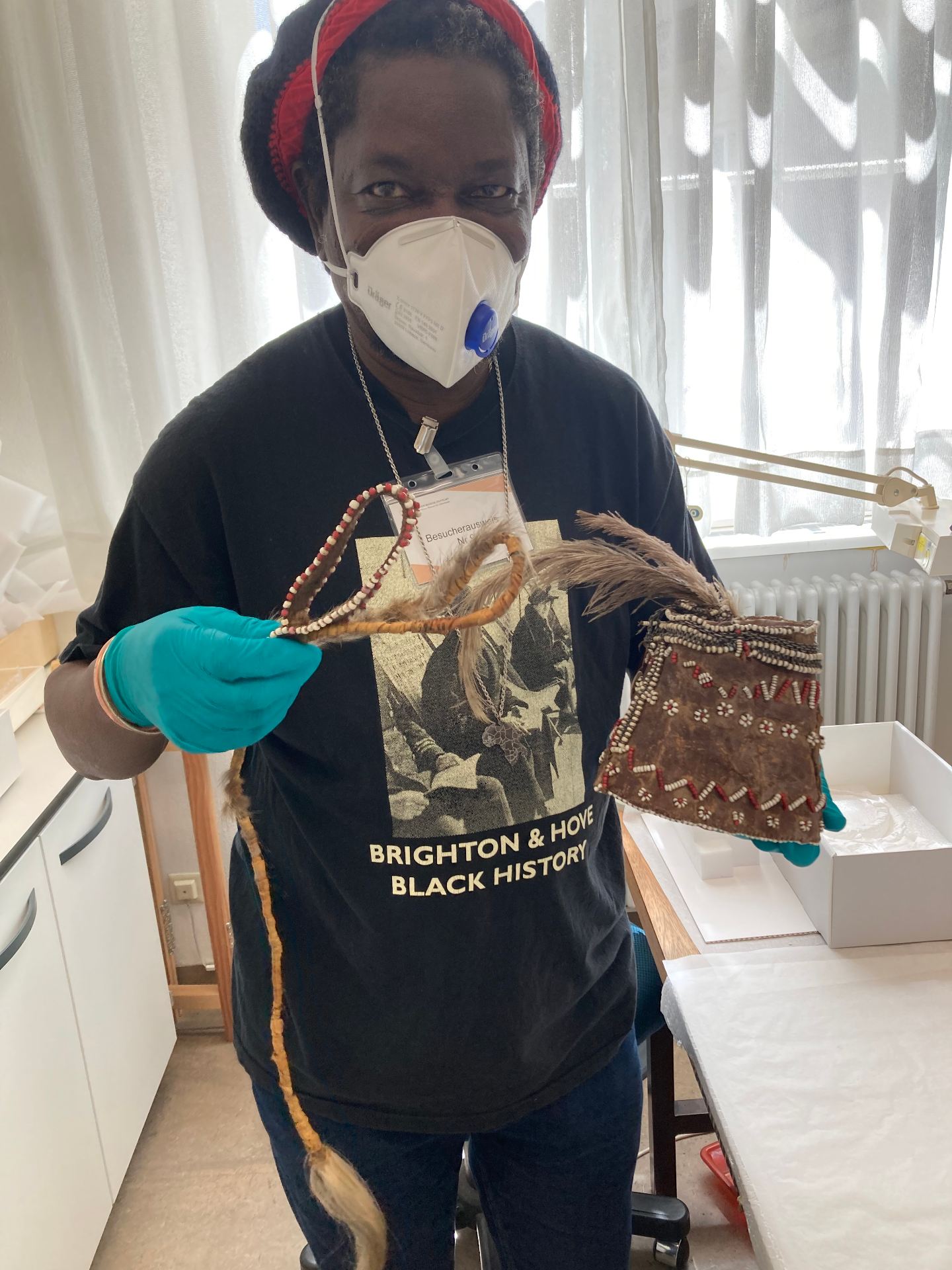

I had considered throughout my studies how invaluable embodied knowledge can be to the dress historian and leaned on Hilary Davidson’s work, the Embodied Turn during my MA in Design History and Material Culture. These were my first moments of getting to handle delicate or complex pieces, like the scented black outfit, and work out how they needed repacking for their future care. In the first image you can see that the delicate mesh collar needed an acid free tissue paper support. Each different garment supplied a new lesson in handling and packing. What unfortunately isn’t pictured, is that inside the sleeves were arm pit pads, small patches that were often inserted into historic clothing to protect the garment from sweat prior to the invention of deodorant. These were sadly disintegrating.

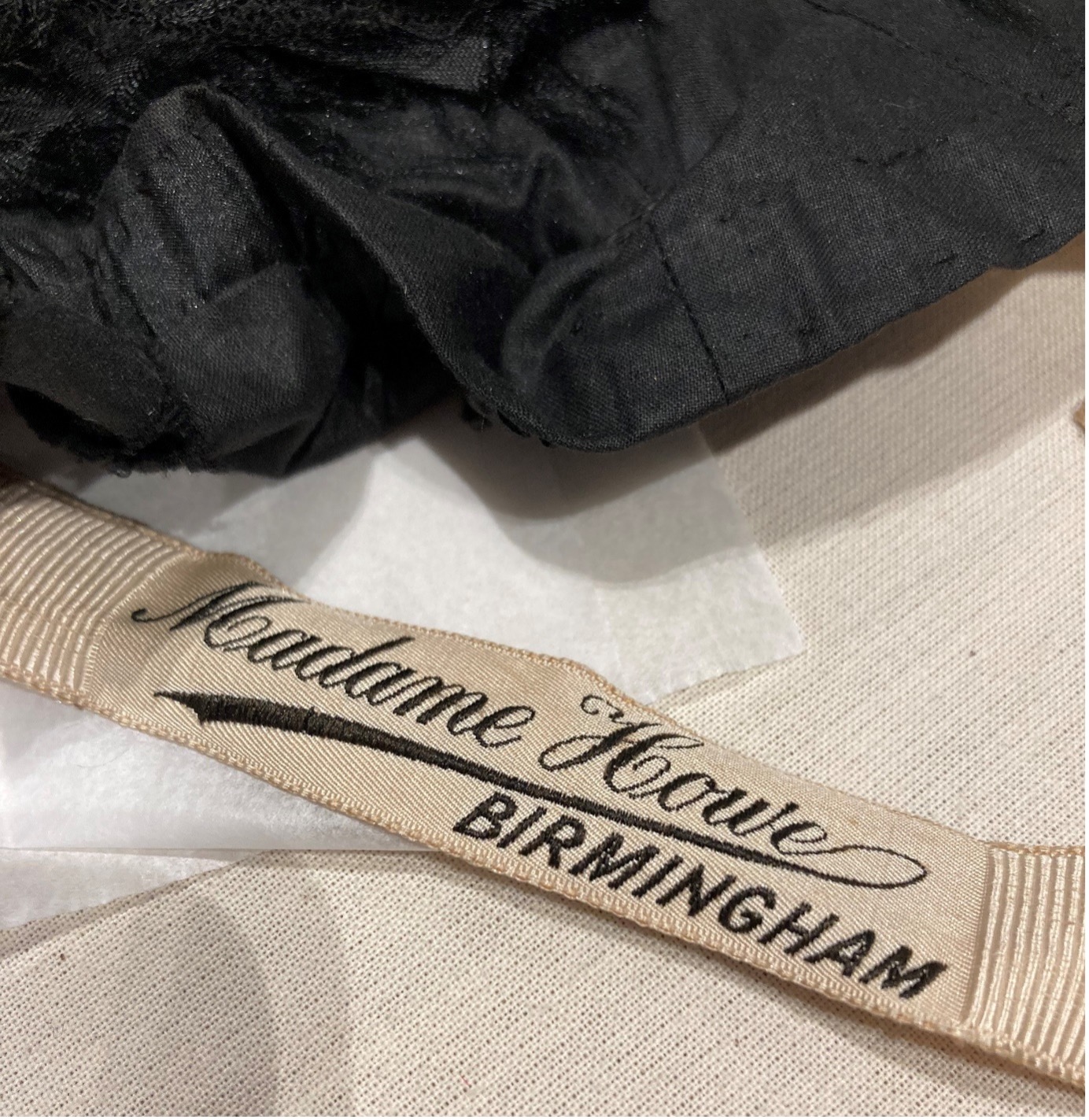

Look at the beautiful label which was hanging off the skirt section of the outfit, which of course provides another exciting line of enquiry. And as PhD student Jo pointed out, the outfit appeared to have been unpicked and adapted, the stylistic elements lending itself to an outfit from the previous century. It’s exciting details like these which are an utter privilege to witness up close and remind us how Material Culture study is an exhilarating way to decipher the past.

Photograph of 1917 Black Taffeta Day Dress, Label. Worthing Museum 4302 1-2. 11/11/22. Author’s Personal Collection.

This experience made me feel incredibly grateful for the handling workshops I undertook at Brighton Museum as part of the Caring for Collections and their Users Module, a core module for the MA Curating Collections and Heritage. This mixture of both object-based work and practical and theoretical study provided a rounded background in both the academic and the practical. On the module, we read industry-led incentives from the Museums Association and discovered scholarship on museums and heritage that help contextualise this world, like George Hein’s book, Learning in the Museum. We had sessions on Integrated Pest Management, and learnt what on earth accession numbers actually mean! Importantly, handling workshops taught us how to make a simple acid-free tissue paper pouffe, a crucial part of the packing process of course! All these insights allowed me to approach my newfound volunteering position with confidence.

As you can imagine, a fantastic bonus of volunteering with the dress collection at Worthing Museum is how much it has inspired further study, from researching different historical dressmaking techniques (remaking as methodology is one of my areas of special interest), to trying to better understand the varying forms of production during a specific period, or simply looking up other examples in this collection and beyond to better understand clothing cultures of a certain style. But sometimes there is just the simple joy of discovering a garment you have never seen before like the incredible 1920s crochet dress.

Photograph of gold coloured 1920s crochet dress. Worthing Museum 1976/277/1. 11/11/22. Author’s Personal Collection.

I am only a few weeks into this experience, and I already feel so inspired, not only to see what else this position has in store, but it has confirmed how I wish to work further in this environment, and to contribute to research in fashion and dress in this material manner.