Hannah Rumball, PhD candidate, documents an extraordinary day in Bermondsey, London.

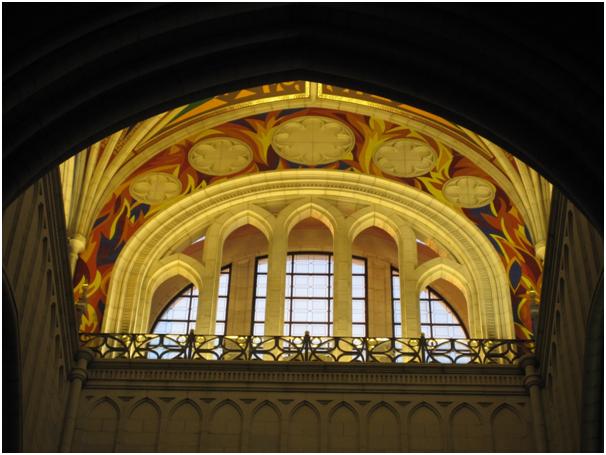

Founded in 2003 by British fashion designer Zandra Rhodes, and still functioning as her London residence and studios, the Fashion and Textiles Museum presents a constantly changing series of design and jewellery exhibitions operated in association with Newham College. On 4 June 2013 the MA History of Design student group, joined by Professor Lou Taylor and Dr Annebella Pollen, were given unprecedented access to the museum’s current exhibition, Zandra’s cutting and print room, and even to her home. As Curator, our fellow Masters student Dennis Nothdruft was in a perfect position to provide an intimate behind-the-scenes tour of the site.

The day commenced with a visit to the hit show Kaffe Fassett: A Life in Colour. The gallery space had been skilfully curated as a unified flowing composition that also managed to represent the core themes of each of the craft practitioner’s creative phases through painting, knitting, textile design and quilting. The relatively modest size of the exhibition space and the overlapping arrangement of the exhibited pieces created an intimate and homely environment for the textiles, much as you may imagine Kaffe envisioned them in use. A heavy wool knitted handmade cardigan, for example, draped over the back of a chair, sat as if its owner had just abandoned it. A Wedgwood-inspired cabbage teapot stood as if ready for pouring amidst the vegetable and flower motifs of Kaffe’s Berlin wool work pillows and needlework furniture coverings. This compilation of recent and earlier pieces, featuring an example of the Victorian ceramics that inspired his earliest works and which he reinterpreted through his bold colour palette, was organised as a psychedelic garden tea party on the mezzanine floor in the space’s most striking curatorial composition. The exhibition perfectly reflected the life’s work of its subject yet also combined it effectively with the bold and distinctive aesthetic favoured by the gallery’s founder.

Widely recognised as one of the world’s most distinctive designers, Zandra Rhodes’ career has spanned more than forty years. Rhodes originally studied printed textile design at the RCA, and this practice is still central to all of her creations. Her distinctive hand-printed fabrics formed the basis for her first fashion collections, with which she crossed the Atlantic to be featured in American Vogue in 1969. Her international profile among the new wave of British designers during the 1970s helped bring the London scene to the forefront of the fashion world. Renowned for her safety pin-adorned, torn and beaded punk-inspired creations, she later went on to dress Diana, HRH Princess of Wales and Freddie Mercury, amongst others. Her designs continue to adorn well-known figures, including Sarah Jessica Parker and Helen Mirren, for both awards ceremonies and on-screen roles. In addition to her clothing brand, Zandra’s current output includes costume and set design commissions for opera performances around the world. Her tireless work in the field of fashion was honoured with a CBE in 2007. She has also received a spectacular nine Honorary Doctorates internationally and is Chancellor of the University of the Creative Arts. Zandra’s bright pink hair, theatrical make-up and daring jewellery have also made the designer into an icon as recognisable as any of her gowns.

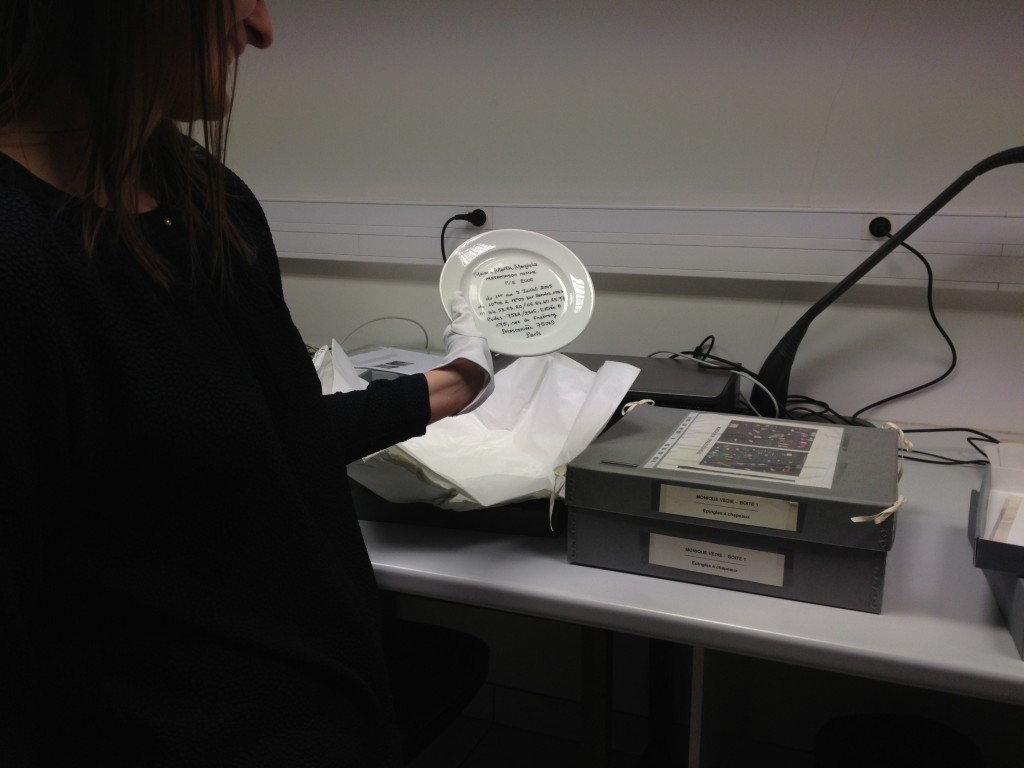

Such exhaustive creativity can be witnessed first-hand when entering the rabbit warren of studios, offices and private rooms that make up the behind-the-scenes of the Fashion and Textiles Museum. Steep, narrow stair cases, lushly carpeted in bold patterns and crammed with artworks, connect the myriad of functional quarters that operate as separate sites for each of the specific stages in her creative process. Wandering through, every wall positively groans under the weight of stored and displayed material; every nook and cranny houses a design, swathe of fabric, finished garment or magazine from any of the past 40 years of her career. Zandra is a meticulous collector and archivist of her own practice and nowhere is this more evident than in the textile design studio in the lowest sector of the complex. As a functional site, the uncharacteristic concrete floors and grey walls signal the dirty-hands nature of the artistic work undertaken in the area. An enormous print table, easily 10 feet long, is bordered by neatly arranged wooden markers and screens organised likes books in a library. While digital techniques have been latterly introduced into Zandra’s textile design practice, this screen printing area is still a hub of activity. The print room also houses all of her original screens dating back to the 1960s, featuring her most iconic patterns. As we huddled around the expansive work bench, like children at an oversized dinner table, Dennis Nothdruft explained the function and significance of the space as creative site of inception, realisation and archive.

For many, however, the highlight of the visit was lunch in Zandra’s private flat, with the designer herself joining us for an M&S sandwich and a chat. Zandra’s vocal opinions remain razor sharp, and she keeps her finger firmly on the pulse of the international fashion and gallery scene. Perched on a leather lounger, surrounded by architectural plants, flamboyant artworks by the likes of Andrew Logan and a collection of her extraordinary dresses on rails in a corner, Zandra had the perfect backdrop as her private rooms reflect the kaleidoscopic aesthetic of her professional and personal style. With rainbow shades of blue, green, yellow and hot pink adorning every wall of the rooftop space, Zandra’s vision comes fully alive in the space she calls home. Venturing out onto the rooftop terrace, only the stunning views of a baking hot London skyline reminded us of the outside world.