Emmy Sale (BA Fashion and Dress History graduate 2018) on taking part in Worthing Museum’s Objects Unwrapped study day

Figure 1. Left: Wendy Fraser’s unfinished patchwork dating to the 1980s that once had used envelopes and the cover of a child benefit book as the backing papers. Right: the 1830s patchwork quilt in Worthing Museum’s collection, that has reused papers from an unknown source but many show prices, names and places. Despite being made 150 years apart, each quilt uses the same hexagon shape and reuse of paper to produce patchwork pieces.

30th June 2018 marked the launch of the Objects Unwrapped collaborative project between University of Brighton and Worthing Museum and Art Gallery. The study day held at Worthing Museum and attended by staff and students from the university and members of the public, consisted of short presentations by BA, MA, PhD students and staff who shared hidden histories of objects from the archive. The presentations ran in chronological order featuring a range of objects from Worthing Museum and Art Gallery archive including: an 1830s patchwork quilt, Kashmir Shawl coat (1883-85), 1892 library campaign, an Edwardian Blouse, 1930s hand-knitted bathing suit, Second World War map dresses and oral history recordings conducted by former Worthing Museum curator Anne Wise. The objects were also on display at the event, allowing audience members to have the chance to see them up close and not just through images in the presentations.

The event was very enjoyable and ignited an interesting discussion. The audience began to relate the objects and their hidden histories to their present lives and practices, in order to understand them further, proving how relevant their stories still are. Karen Scanlon (MA History of Design and Material Culture student) spoke about the oral history tape recordings from the costume collection that included an interview with Esther Rothstein, a dressmaker in Brighton from 1930 to the 1950s. Members of the audience were concerned with the future of the tapes and questioned if they would be digitised to become easily accessible in the future. Wendy Fraser (BA History of Art and Design graduate 2018), shared her reflections on Bridget Millmore (PhD, 2015)’s presentation on the 1830s patchwork quilt. She was fascinated by how it reused various paper scraps for the backing of the patchwork pieces and compared it to a 1980s unfinished patchwork in her own collection that used the cover of a child benefit book and envelopes as the backing. Another audience member, in response to lecturer Annebella Pollen’s discovery of the 1892 library campaign pasted in the back of a notebook, shared that Hove library will be celebrating its 110thAnniversary this year; thus further highlighting that 126 years later it is still a pertinent document in the current climate.

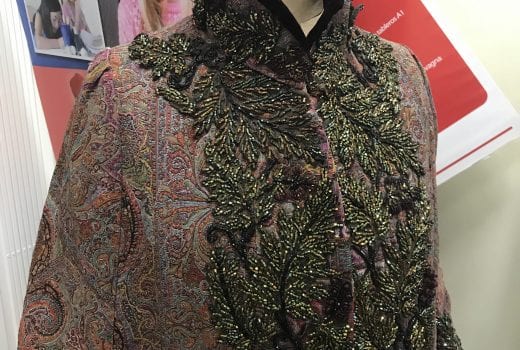

The presentations also highlighted histories of the handmade, upcycled and unfinished. Emeritus Professor Lou Taylor discussed her favourite garment in the collection, an 1883-1885 coat that was radically altered from an Indian Kashmir Shawl. PhD student and lecturer Suzanne Rowland spoke about how her remaking and re-enactment of an Edwardian blouse for a Suffragette costume for Lewes Bonfire night 2017. Lecturer Anna Vaughan Kett shared how silk escape and evasion maps from the Second World War became upcycled as garments after their release to the public in 1945. The objects greatly intrigued the audience and highlighted an interest for an exhibition exploring objects of this nature. The importance of revealing the hidden histories of objects held in Worthing’s archive was also highlighted and I think we all learnt something new and fascinating!

Figure 2 Professor Lou Taylor’s favourite garment from Worthing Museum’s costume collection, an Indian Kashmir shawl that has been radically transformed into a fashionable coat for 1880s Paris.

The event was also my first time speaking in a public setting about my research. My presentation focused on a 1930s hand-knitted bathing suit that I had viewed in the archive for my undergraduate dissertation research. I discussed the factors of cost, adaptation and originality of design that led to its making in the 1930s alongside a brief context of sun worshipping in the period. I also concluded that due to the bathing suit being made in the home, with modest materials and no named designer, some museums would reject the garment. However, Worthing’s acceptance of the garment into the collection in 1981, allows these otherwise hidden histories of ordinary women’s lives and experiences to be remembered and studied. In the audience discussion at the end, one audience member commented on how my talk had reminded her of her childhood and how the first bathing suit wore was hand-knitted. This formed an appreciated addition to the knowledge shared in the presentation, as I mainly discussed why they were made, rather than what they were like to wear. Although I was very nervous before my talk as I listened to my fellow Objects Unwrapped members eloquently present their research, I was also thrilled to share my research with an audience of interested public members and familiar faces from the University. It was a great first experience to talk in a situation outside of a university seminar and contribute to the project’s first event. I hope the experience will help me for future presentation at MA level.