BA (Hons) Fashion and Dress History student Olivia Terry on the allure of old photographs

There is something wildly intriguing about old photographs. A singular moment, caught by chance, is suddenly trapped in time, and is immortalized by the sepia tint that encases it. The people caught in the photographs go on to live their lives, but eventually fall victim to time like everyone else, and soon a lifetime has passed, and their memory has been forgotten by those around them. Their photograph is put away in a box, and begins to collect dust and soon fades with an aged yellow, and darkness surrounds the image. But suddenly, light and air overwhelm the photograph, and it has been rediscovered. I delight in this rediscovery; I find my inspiration in everyday people from the past, found in these images.

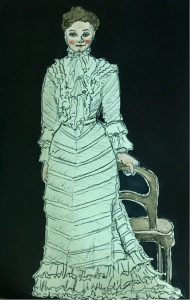

Fig.2: Olivia Terry. Young and Marry. C. 2018. Watercolour, pen, and colored pencil. 5.5 x 3.5 in. Brighton.

It all began when I was digging through my grandmother’s collection of books, when I found a dusty scrapbook hidden on the bottom left corner of her bookshelf. Inside was a collection of photos of her and her family dating back to her birth in 1940. A brunette baby girl held by smiling parents on one page, was replaced by a chubby toddler on the next. The further one progressed in the photo album, the older the child got, soon turning into a young woman. But what really held my interest were the tales behind each photograph, and the people that were frozen in them. My grandmother connected each photograph with some fragmented yarn of a story, but other times, when her memory failed her, I made ones up.

Before I knew it, I was looking beyond my family’s photographs, and discovered the treasures that lie in antiques stores. I was able to spend hours in them sifting through faded photographs of individuals, couples, families, pondering the mystery that lies behind their eyes, and the story they each possess. What were the events that preceded the photograph being taken? Who were they? Where were they headed after the picture was taken? It was these sorts of questions that fed my creative mind in game playing, story writing and art creating. Sepia tinted photographs of woman donning calico and bonnets led me to pretend I was a pioneer woman navigating her way through the vast wilderness by a nearby copper-colored creek. A hint of a smile could inspire an entire story. Their mystery has always been my muse.

When I attended events at my high school in Boise, Idaho, I made a point to pass the framed senior portraits of 1917, and allow my mind to wander, and consider each person’s place at the school; their social hierarchy, what clubs they may have belonged to, and possible personality traits. I am fascinated by the unknown of each person, and delight in deciphering the hints present in photographs: the expression on their faces, the chosen objects featured, the settings, and most importantly, the clothing they wore.

High collars, meticulously pleated skirts, and mutton-chop sleeves caught my attention like a snagged thread. I fell in love with the whole aesthetic of women in big skirts in colorless photos, and soon my inspiration in the photographs was found in something more tangible than just my thoughts, when I began to draw them. I loved the way my fingers felt when I drew the creases and folds of fabric, and how my mind produced romanticized thoughts when I gave the women rosy cheeks, bringing life to the original eeriness. I am able to imagine the bright, cheery nature behind silk taffeta evening gowns and I can fathom the darkness found in black silk-crepe mourning dresses. It is expressed through the intensity of my pen strokes, the colors I choose, and the amount of contrast between light and dark. Drawing their clothing inspires a connective feeling in me, and with each mark of my pen, I feel as if some bit of their mystery is solved.

Clothing is a powerful tool. Something as simple as a shade of black, a cut in style, or the placement of a patch, has the rare capability to communicate a profound amount about a person — their culture, their time period, their social status, their personality and interests, their religious beliefs, their nationality, their occupation — all without really muttering a word. It can bring life back into bygone stories, because it speaks so personally about the people who wore it. Putting the spotlight on clothing from the past, by studying and restoring it, is what I long to do. I get excited thinking about the way a person’s identity shows through their clothing through the choices made: the color palette, the social connotations, and how the materials varied depending on the resources available to that person. A person’s character shows through their clothing, whether they intend it to or not. Each garment has an individual narrative; and to comprehend that story means to consider everything from the inspiration, to the construction, to the context. Each part makes up a story I am dying to read.

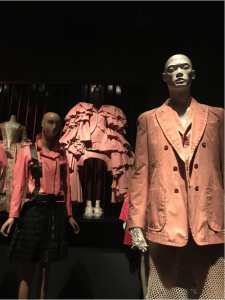

Fig. 6: Olivia Terry. a Change in Season. C. 2018. Acrylic, colored pencil, and ink. 16.75 x 23.25 in. Brighton.

There are so many narratives that go untold. Lifetimes pass by, and words and memories yellow like paper, and soon, not much can be said or remembered about a person. New stories take the spotlight over the old, until they too are replaced and stored away in old hat boxes and photo albums. But when an old photograph re-surfaces, there is nothing that provides greater insight into the lives of the people pictured than their attire. Because that’s the thing; there is a beauty in historical dress that remains true and constant. A beauty that cannot be muted by the dust it may have collected, or the decades that have passed. It says something deeply intimate about an individual. With the help of studying historical fashion, I want to uncover the stories packed away, and bring light to the ordinary people of years gone by, because quite often, their story is not ordinary at all.