PhD student Jenny Roberts on working on the V&A’s forthcoming Mary Quant show

Ever since studying dress history for my BA in History of Art and Design at the University of Brighton I have dreamt of working at the V&A in the Fashion and Textile department. Many years later, as a PhD student, I finally achieved this ambition as part of a funded internship courtesy of my AHRC funders, Design Star and University of Brighton. It was everything I had hoped for and more.

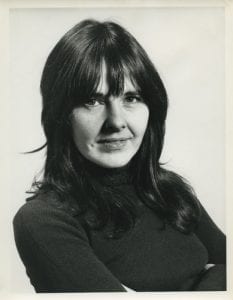

Fig. 1 Daily Mirror – Wednesday 17th March 1965, p.1

For six months I worked exclusively on researching and planning the Mary Quant exhibition, due to open on 6th April 2019. Jenny Lister, one of the exhibition’s curators, has been wanting to hold a Quant retrospective for many years. The previous lack of attention is astonishing considering her market presence from the mid 1960s to the late 1970s. Although the Museum of London held ‘Mary Quant’s London’ in 1973, a full assessment of her work is timely. The V&A’s exhibition will trace the journey of the Mary Quant brand from her original shop to a worldwide market where her name featured on clothing, hosiery, hats, spectacle frames, umbrellas, jewellery and make-up homeware, home furnishings, carpets, paints and wallpapers, and beds. Mary Quant was even used to promote Hotpoint washing machines!

From the beginning of the exhibition process, the curators wanted to steer away from preconceptions of 1960s psychedelia and to articulate a more measured appraisal of Mary Quant’s work and output. It is this narrative which will surprise and interest visitors to the exhibition when it opens.

Fig. 2 J. C. Penney’s Catalogue 1966

The Mary Quant business began as a single boutique in Chelsea, London in 1955, which had transformed into a worldwide brand by the mid-sixties. Quant recalled in her autobiography that: ‘It was utterly impossible…to envisage that within seven years the business would go well over the million mark and the clothes I was to design would be in 150 shops in Britain, 320 stores throughout America and also on sale in France, Italy, Switzerland, Kenya, South Africa, Australia, Canada and, in fact, in just about every country in the western world’.[1]

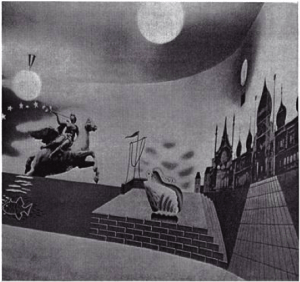

Fig. 3 Wool Jersey dress V&A T.352-1974

In 1953 Mary Quant graduated with an Art Teacher’s Diploma from Goldsmiths College, where she met her future husband, Alexander Plunkett Greene.[2] Archie McNair, who made up the team, was a qualified lawyer and photographer and owned a café in Chelsea. His legal acumen was used to their advantage when negotiating branding deals. Together they invested £10,000, a substantial amount of money in 1955, opening a boutique shop in the Kings Road. Bazaar, as the shop was named, became renowned for its playful and amusing shop window displays and became a destination shop for a growing affluent younger market. Another Bazaar opened in Knightsbridge in 1957. In 1962 Mary Quant visited America and, as a result of this visit, she began considering mass production techniques in her designs. Her involvement with American department store J.C. Penney’s was marketed to the American audience emphasising Mary Quant’s pivotal role in ‘Swinging London’ at a time when London considered ‘cool’.

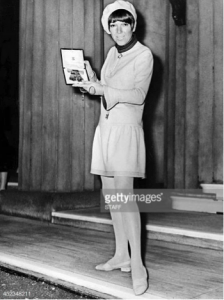

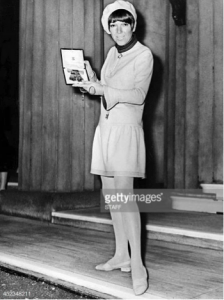

Fig. 4 Mary Quant pictured wearing a jersey dress from her own collection at Buckingham Palace with her OBE award, 1966. © Getty Images

In 1963 Mary Quant launched her more affordable range under the label ‘The Ginger Group’. This range of clothing incorporated some of the mass production techniques she had learnt from her travels to America and was reflected in the design and the fabrics chosen. A film clip reveals Mary Quant’s thoughts on what she considered the time-consuming and expensive nature of haute couture. She felt that “clothes should be made by mass-production when we live in a mass-production age.”[1]There were multiple derivations of a design, like for example her ‘Banana Split’ dress made in a black jersey fabric.

These jersey dresses were easy to wear and care for, available in a rainbow of colours as well as variations of the original design. The success of the Mary Quant brand was equally due to her and Alexander’s imaginative and playful marketing as much as it was due to the circles in which they mixed. For example, before he became the Rolling Stones’ manager Andrew Loog Oldham was employed to dress Bazaar’s windows.[1] Crucially, whenever Mary Quant featured in articles or in public, she was dressed in her own designs. In 1966 Mary Quant received her OBE for services to the British fashion industry at Buckingham Palace. She was pictured in newspaper articles holding her award wearing one of her Ginger label jersey dresses. She implemented this marketing strategy even when advertising her collaborations with other manufacturers. In the advertisement for Mary Quant berets made by Kangol all the models wore jersey dresses from the Ginger Group label. Similarly, when her shoe range Quant Afoot was launched the models all wore her designs.

Fig. 5 Advert for Mary Quant’s collaboration with Kangol

I started my V&A internship when the museum had just taken delivery of the Plunkett Greene archive, which included private papers, marketing material, Daisy Dolls, Daisy Dolls’ outfits, fashion photographs and garments worn by and designed by Mary Quant. The first few weeks were spent on cold, November days in the Cloth Workers Guild at the V&A’s Blythe House photographing, dating and cataloging the previously unseen contents of the archive. From there we moved on to creating boards documenting the items held by various institutions throughout the world.

These boards were an essential visible aid in the formulation of the story of the exhibition. Thematic boards were then created and once the ‘story’ had been agreed consideration moved onto the restrictions imposed by the physical layout of the exhibition space and the display cases. One of the first problems facing all curators staging an exhibition in the V&A’s fashion galleries, is navigating display cases and available space. Without giving anything away, I feel that what is sometimes considered a problematic space has actually lent itself to the narrative of Mary Quant’s journey, from a single boutique shop to global brand.

Fig. 6 Mary Quant and models at the Quant Afoot footwear collection launch, 1967 (© PA Prints 2008)

The whole process of designing the exhibition was extremely collaborative. The team presented their ideas on the direction of the exhibition’s narrative not only to colleagues within the V&A, but also to external practitioners and academics. These meetings were constructive, with warm exchanges of ideas and knowledge. At the same time, part of the ‘Mary Quant Team’, as we had become known, researched contextual images, advertisements, stockists and articles featuring the designer in the National Arts Library’s magazine collections. Unusually, the curators Jenny Lister and Stephanie Wood decided to announce an earlier than usual call-out for the exhibition as they wanted to include stories of the impact Mary Quant had had on her generation. In particular they wanted to hear from debutantes, who had been some of Mary Quant’s early clients as this market has been overlooked in previous Mary Quant narratives. But crucially the curators wanted to understand the impact of Mary Quant’s design brand whether clothes, make-up, tights, hats or interior furnishings. The range and extent of her designs were far-reaching, and markets opened up in America, Australia, Europe and China.

My experience taught me a great deal about how to plan and carry out exhibitions. The process is similar to the PhD journey in that to begin with there is an enormous amount of what seems disparate material, which needs to be sifted through to assist in the telling of a story. This material is then edited down to form a focused narrative. Unfortunately, my internship ended before I could get heavily involved in the design of the exhibition space. Even so, I am excited to see the finished exhibition, knowing that I played a tiny part in a long over-due appraisal of the work of a designer who was responsible for disseminating the ‘London Look’ around the British Isles and across the world.

The V&A Mary Quant exhibition opens Saturday 6thApril, 2019. The book that accompanies the exhibition, Mary Quant by Jenny Lister (London: V&A), will be published on 25th March 2019.

Bibliography

Beatrice Behlen, A Fashionable History of the King’s Road. London: Unicorn, 2017. Print.

Breward, Christopher, Fashioning London: Clothing and the Modern Metropolis. London: Berg, 2004. Print.

— David Gilbert and Jenny Lister (eds), Swinging Sixties.London: V&A Publications, 2006. Print.

Booker, Christopher, The Neophiliacs: Revolution in English Life in the Fifties and Sixties. London: London: Collins, 1992. Print

Buckley, Cheryl & Hazel Clark, Fashion and everyday life: London and New York. London: Bloomsbury, 2017. Print.

— and Hilary Fawcett, Fashioning the Feminine. Representation and Women’s Fashion from the Fin de Siecle to the Present. London:I.B.Tauris, 2002. Print.

Donnelly, Mark, Sixties Britain. London: Routledge 2005

Fogg, Marnie, Boutique: a ‘60s cultural phenomenon. London: Mitchell Beazley. Print.

Green, Felicity, “The mini-skirt makes its debut at Ascot….and it’s a winner”, Daily Mirror, 15 June 1966.

Kynaston, David, Austerity Britain 1945-51.London: Bloomsbury, 2007. Print.

McRobbie, Angela (ed.), Zoot Suits and Secondhand Dresses: Anthology of Fashion and Music. London: MacMillan. 1989.

Morris, Brian, An Introduction to Mary Quant’s London.London: London Museum, 1973.

O’Neill, Alistair, London – after a fashion. London: Reaktion Books Ltd, 2007. Print.

Quant, Mary. Quant by Quant: The Autobiography of Mary Quant. London: Headline, 2012

Wilson, Elizabeth, Adorned in dreams: fashion and modernity. London: Virago, 1985. Print

https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/introducing-mary-quant

https://www.dailymail.co.uk/debate/article-2096184/Mary-Quant-swing-60s-gave-iconic-bob-cut–hallelujah–invented-waterproof-mascara.html

https://artsandculture.google.com/exhibit/0QKSHn4SqTdrLw

[1]Donnelly, Mark, Sixties Britain. London: Routledge, 2005. Print. p.92

[1]https://youtu.be/cyLa5WZ8VO4Accessed 10.10.18

[1]Ibid Locations 675-678

[2]Ibid Location 90

Fig. 1

Fig. 1