The breadth of topics at the University of Brighton’s international conference on Textual Fashion impressed and inspired Alice Hudson (BA (hons) Fashion and Dress History)

Recently I had the pleasure of attending the ‘Textual Fashion: Representing fashion and clothing in word and image’ conference which took place over three days at the Grand Parade campus and which was organized by the University of Brighton’s Charlotte Nicklas and Paul Jobling.

Having never been to a conference before, I wasn’t sure what to expect, but it turned out to be an invaluable source of information and education, opening up new discourses that I had never previously encountered or even considered. Due to the sheer number of speakers over the course of the conference, the papers were split into strands containing three papers each, connected by a general theme, and three strands would be on at the same time, making deciding where to go a challenge. The number of papers that attendees had the chance to listen to over the duration of the conference was a little overwhelming. Although sitting down all day listening to other people speak doesn’t sound like it would be physically draining, it really is – it’s a good job there was plenty of tea and coffee!

There was a large variety in terms of speakers, including every career level from MA students (a couple of whom came from Brighton’s History of Design and Material Culture MA) to well-known academic researchers who are paving the way in their chosen field. It was wonderful to see papers from Brighton tutors, including Charlotte Nicklas’ paper on the appearance of the ‘Bright Young People’ in interwar novels and Jane Hattrick’s on fashion designer Norman Hartnell’s appearances in women’s magazines.

On top of the twenty-minute papers and discussions we also had truly fascinating talks from keynote speakers Jonathon Faiers and Stephen Matterson, but it was Agnès Rocamora’s paper “Making It Up As you Go Along: Labour and Leisure in the Fashion Blogosphere” that really struck me. As someone who follows a lot of fashion blogs on various digital platforms and social media sites, it was interesting to have an insight into the work of those bloggers and how they negotiate their work in what is still a relatively new platform/form of labour (hence the title). She discussed ideas such as Lazzarato’s ‘Immaterial Labour’ and Terranova’s ‘Free Labour,’ the latter of which seems all the more relevant in the current fashion industry which so heavily relies on unpaid internships.

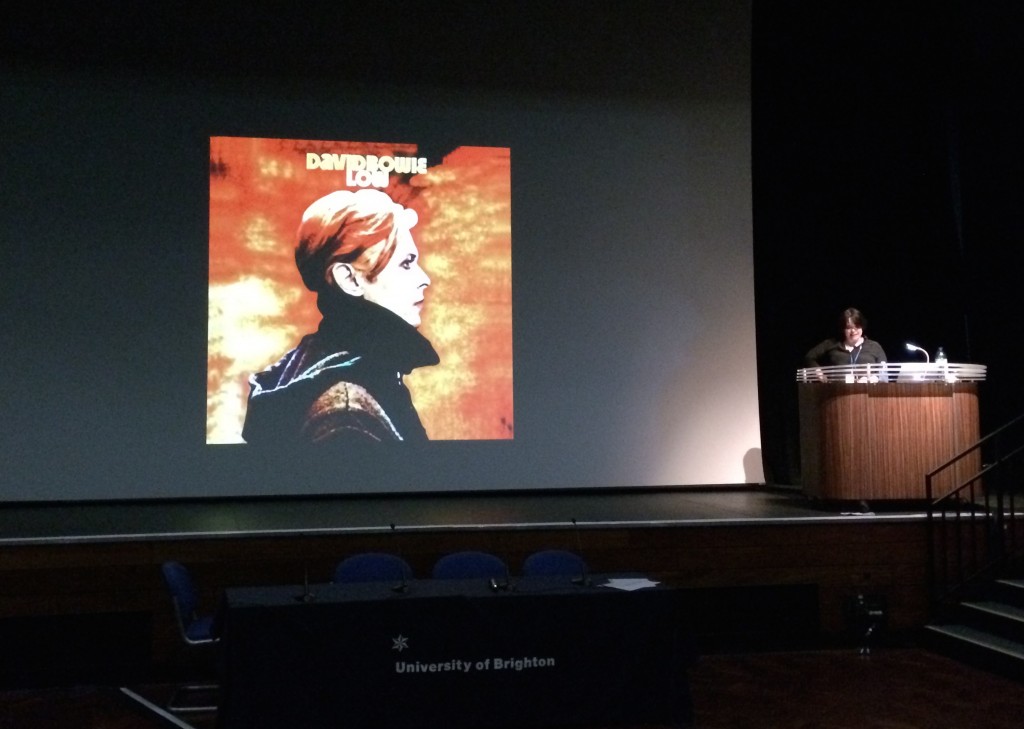

Mairi MacKenzie speaking about ‘The Man Who Fell to Earth: Bowie, Football & Fashion in Liverpool 1976-1979’

With such a huge range of subjects covered within the title Textual Fashion, including cinema, literature, magazines and more, the conference was undoubtedly a success in providing food for thought. Other highlights of the conference for me were hearing Mairi MacKenzie’s insights into the sartorial influence of David Bowie on football fans, or “casuals” in Liverpool in the late ‘70s, and Janet Aspley’s research on Nudie Suits, specifically the one belonging to Gram Parsons as she explored the relationship between country music and counterculture.

I would urge anyone currently studying on any of the History of Art and Design pathways to make an attempt to attend at least one conference before the end of their course (and preferably early on). The experience was helpful not only in terms of learning new things and opening up discussion, but also because it gives you an idea of how to present an academic paper (something we all could do with knowing for seminar presentations). It was also a good networking opportunity: you’d be surprised how many interesting people you get to talk to in what was a truly welcoming atmosphere. Plus, you should make the most of student prices before it’s too late!