Sally Jones MA History of Design and Material Culture student reflects on her use of eBay as a resource when access to things were curbed during lockdown.

At the start of my MA last autumn, museums were still partially open, albeit for limited, pre-booked visits, but enough to satisfy my love of being near old things, to soak up their aura and experience the joys of historical artefacts ‘in person.’ I could also use them to complement my studies, visiting Worthing Museum to look at mourning jewellery for my first assignment. Semester two was a different situation altogether. We were in the heart of lockdown three and everything had shut. As a student of material culture this was a challenge. My MA centres around stuff, and for me, my real passion is old stuff. So how to bring my studies to life when I could no longer access museums, historic sites and archives? Life had moved online so I turned to eBay, the virtual equivalent of foraging around a flea market, and what I discovered was that, used wisely, it could be a productive source of primary material.

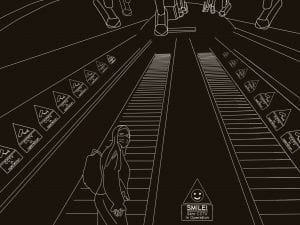

Selection of gas fire themed playing cards purchased from eBay, author’s own collection. Digital scan by author

eBay first came up trumps in supporting a presentation I put together based on a 1937 gas fire catalogue, which is held in the University Library St Peters’ House Special Collection. Basic searches revealed a wealth of ephemeral material and led to some fascinating discoveries, my personal favourite being a ubiquitous supply of playing cards advertising gas fires. Cheap, accessible and in widespread use at the time, playing cards were an ideal medium through which to market domestic technology, although I was unaware of this until I stumbled across them listed for sale. I compared the illustrations to gain a greater understanding of how the technology was mediated. I also looked at the depiction of women, who were prominent in many of the designs, to consider how their role and position within the home was represented and shaped by gas fire advertisements.

Selection of Edwardian postcards purchased from eBay, author’s own collection. Digital scan by author.

eBay continued to be a rich hunting ground for my next assignment, which focused on the use of ridicule in anti-suffrage Edwardian postcards. This time, I purchased a small collection of postcards, printed and posted in 1911. Most online archives of suffrage postcards favour the printed image on the front and neglect the information on the back, but it is the reverse side which bears evidence of contemporary consumption practices. I was able to draw on this from my own case study sample. I could also see how the material attributes of the postcard contributed to its effectiveness as a propaganda device. One of the great advantages of eBay was that the listings photographed both the front and the back of the postcards – you can even hover over the images to pick up finer detail and read the handwritten messages – an option which wasn’t available through online archive records.

Of course, eBay isn’t an archive and researchers should exercise caution, remaining aware of issues around provenance, and titles and descriptions which are designed to sell the item and enhance its appeal, rather than maintain historical accuracy. On the other hand, many sellers are collectors themselves with a knowledge and enthusiasm for their particular specialism. eBay certainly introduced me to artefacts I would not otherwise have been aware of, and it opened up new areas of research, providing inspiration at a time when access to collections was severely limited. The random, ephemeral nature of objects listed on the site makes for a serendipitous approach which I particularly enjoyed. There’s also something about the tangible experience of handling objects that can really enrich a research study and whilst I am very much looking forward to getting back into a museum, eBay proved to be a valuable resource, offering direct access to historic material culture at the click of a mouse.