Helping to de-install the mannequins used for Dame Vera Lynn: An extraordinary life at Ditchling Museum of Art + Craft

MA Curating Collections and Heritage student Harriet Brown reflects on her work placement in textile conservation with Zenzie Tinker Conservation studio.

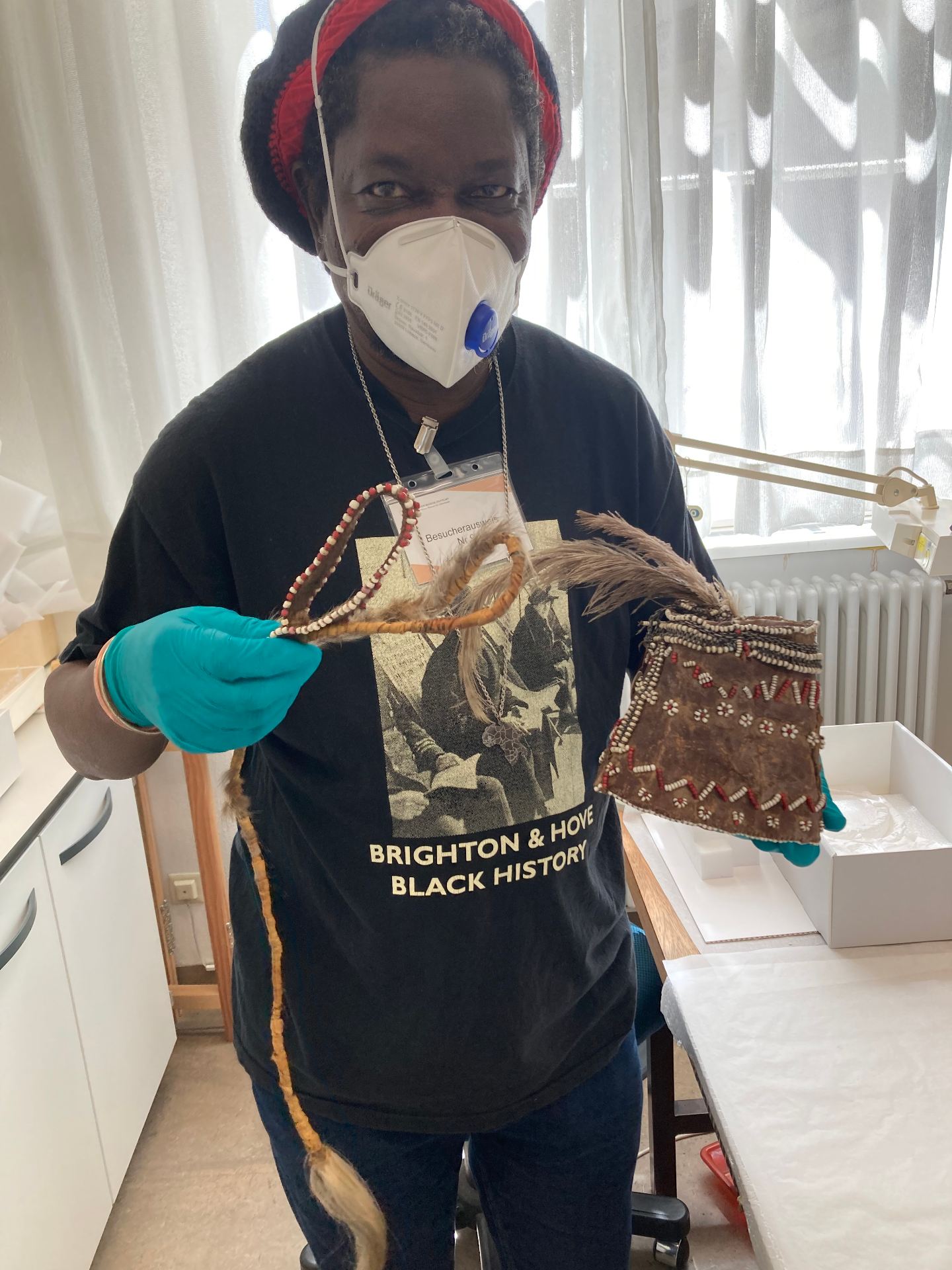

For the placement module of the MA Curating Collections and Heritage, I worked at Zenzie Tinker Conservation (ZTC). This was an incredibly varied placement where I supported a wide variety of projects.

Over 150 hours, I helped with condition checks at Smallhythe Place, the actress Ellen Terry’s Kent house which is now owned by the National Trust. I participated in a shoe mounting workshop at Worthing Museum and helped with the surface cleaning and packing of the Gage family coronation robes for Firle House. I also helped to make mounts for curtains for Rudyard Kipling’s house at Bateman’s, another property owned by the National Trust in East Sussex.

Surface cleaning the Viscount Gage’s coronation robes and the coronation robes on display at Firle House

The main project I worked on during my placement was a patchwork quilt from the ZTC study collection. It joined the study collection after Petworth Cottage Museum decided to deaccession the object. In return, ZTC did some vital conservation work on objects in their remaining collection.

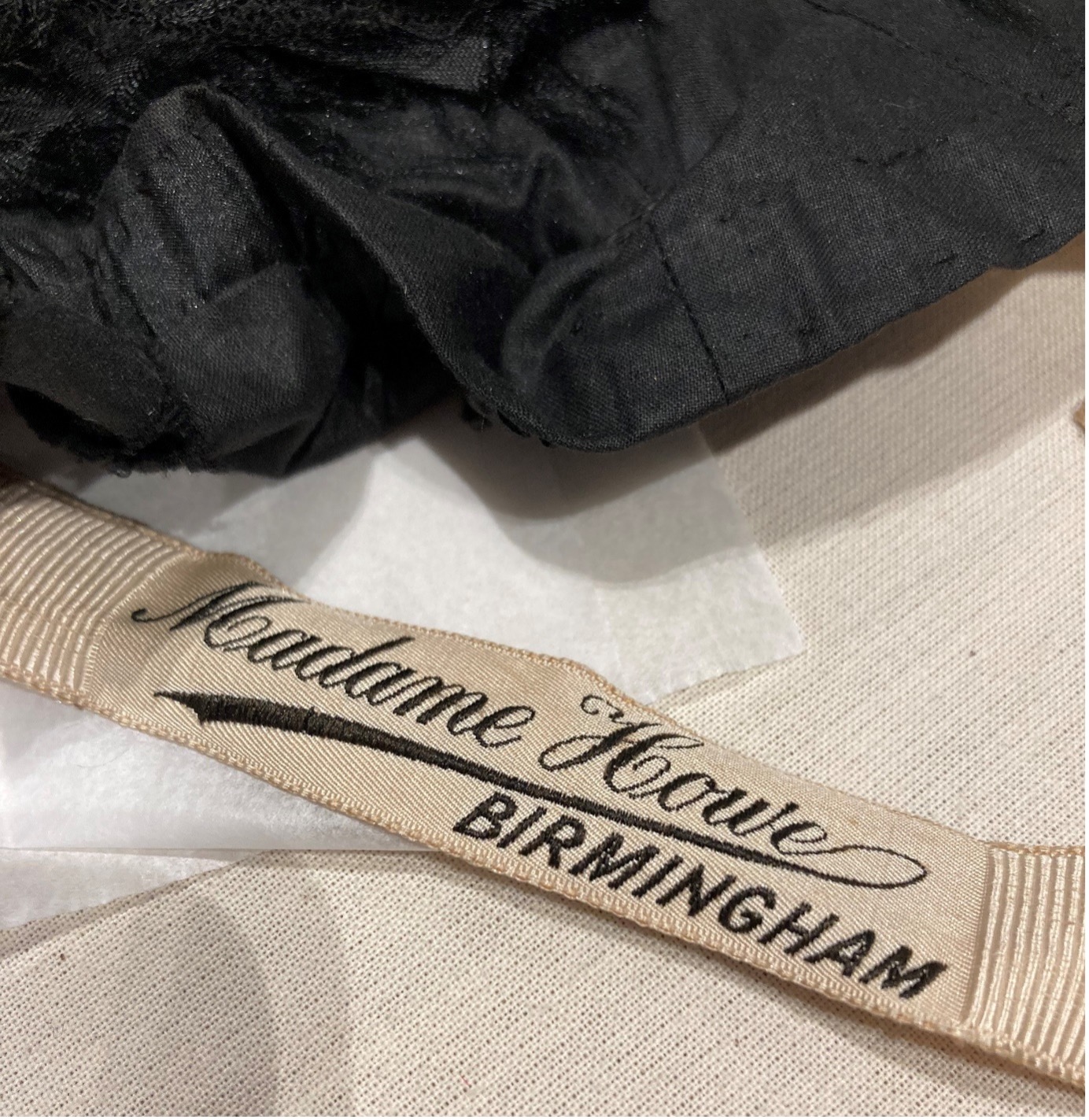

This quilt is a nineteenth-century unfinished patchwork quilt, made from a variety of fabrics, each wrapped around a paper template. The quilt was made by someone (most likely a woman) who lived locally in or near Brighton. I discovered this through my close examination of the patches in the quilt as many of the addresses and names of businesses on the patches that were still readable could be traced to locations in Brighton. These were mostly around North Street and Ship Street. The earliest date I found on the papers was the 2nd of August 1859 and the latest date I found was the 30th of October 1870. The large range of dates in the quilt was likely down to the fact that paper was relatively expensive, so scraps would have been saved up over time to be used in a project of this size. Due to the fact this quilt is over 150 years old, several of the papers have naturally started to show wear and tear. Also, the quilt had at one point been stored folded and so there were several large creases running through the fabric and papers. These both provided excellent opportunities for learning about conservation techniques.

Over the course of the 150-hour placement I photographed the patches and carried out research on the patches that were legible and had names and addresses on them. I also researched the practice of quilt making. Some of the patches had more information than others. For example, from one of the patches I was able to find out about a solicitors firm that had been operating in Brighton from 1775 to 2019! (more information can be seen here).

Once this cataloguing was finished, I then surface cleaned the paper side of the quilt. This was done using a vacuum with a brush attachment on the lightest setting and then going over the fabric part of each patch using a makeup sponge. Once I had carried out the surface cleaning, I was taught how to humidify the patches in order to release some of the creases. However, this wasn’t a very effective method, so we moved to using a vacuum table. Using the vacuum table, I was taught how to remove the creases from the papers and the fabrics, as well as how to use Japanese tissue paper to create supports for the paper patch templates to prevent them from becoming further damaged.

Before and after of two of the patches I conserved on the vacuum table using Japanese Tissue Supports

I am incredibly grateful to have worked on such a large variety of projects whilst on my placement at Zenzie Tinker Conservation as it has helped me to better understand the wide variety of conservation techniques that help make it possible for objects to go on display.