Final year History of Art and Design student Lisa Hinkins reports on Brighton Museum’s recent conference Queer Legacies: Transforming practice in museums and galleries post-2017

I was awarded a bursary ticket to attend Queer Legacies, a one-day conference organised and facilitated by Brighton Museum and Art Gallery. In the last eighteen months the Museum has carried out changes to address the lack of LGBT visibility within its building. It has also positively improved the Museum of Transology that transferred from the London College of Fashion into a space at Brighton Museum that gives gravitas to transgender lives. It has also held successful exhibitions of twentieth century queer artists Glyn Philpot and Gluck, introducing their work and lives to many who had not heard of them before. It was fitting that the Museum held this timely conference in a city rightly regarded as the LBGT capital of Europe.

The programme had a diverse range of speakers from various art institutions in the UK and Netherlands. The Chair for the day was Matt Smith, artist and curator, who holds a practice-based PhD in queer craft at University of Brighton. Smith pointed out that the National Portrait Gallery (NPG)’s Gay Icons exhibition in 2009 set a precedent for museums to consider curating LGBT-specific content. The 2009 NPG exhibition rode on the wave of a changing British society that followed 2005 legislation allowing same-sex civil unions. I had visited this ground-breaking exhibition, which was an incredibly moving experience that allowed celebrated LGBT people, among them tennis legend Billie-Jean King and singer Elton John, to select images of historical and contemporary LGBT heroes, displayed in an illustrious setting. Smith went on to say that since the NPG show, many art institutions had failed to collect and display LGBT objects, but that in the last few years there had been an exponential rise in queer exhibitions and displays. He said it is important to speak up, to understand the diversity of queer experiences. The failures of the past are gradually being addressed, though importantly he noted that the LGBT community still looks white, male and middle-class, and that this needs to change.

Next to the conference lectern were representatives from Amsterdam Museum. They expressed the importance of incorporating the ‘domestic narrative’ in exhibitions. By this they meant that the community in which a museum is set needed to be recognised, so that ‘out-reach’ becomes ‘in-reach’. For this to succeed, they recruited volunteers to assist with curating exhibitions. It was, they explained, important to the museum that it is custodian of a usable collection that grows and does not die. One important object, The Rainbow Dress, consists of seventy-two flags sewn together to represent the countries that still deny LGBT rights. The dress is touring round the world as a piece to inspire discourse on human rights and equality.

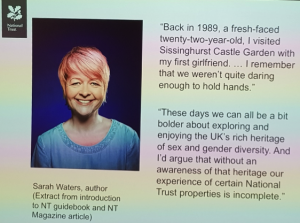

Fig 2. National Trust slide. Sarah Water, author extract from NT guidebook. Author’s own photograph. 7 Mar. 2018.

The National Trust recognised that it needs to reflect social progress to ensure better engagement with the public. The Trust’s speaker talked about the Prejudice and Pride guidebook written by scholars of gender and sexuality Alison Oram and Matt Cook, which highlighted Sissinghurst Castle and Garden. Its history was addressed through Speak its Name: a collaboration between National Portrait Gallery and the National Trust focusing around portraits held at Sissinghurst of its owners Vita Sackville-West, Harold Nicholson and their contemporaries such as Virginia Woolf , which gave greater voice to its famous owners’ queer lives. From the Pitt Rivers Museum, an impassioned Dr Clara Barker stated that museums are powerful tools, which can be harnessed by communities to readdress the disparities of those written out of history, by telling their stories through objects held. These points were further touched on by Clare Barlow, the curator of Tate Britain’s Queer British Art, 1861-1967, who said the past is queerer than you think. By examining and exploring art and objects, histories are told.

The last exhibition addressed at the conference was the Museum of Transology, currently on display at Brighton Museum. Curator E.J. Scott said that it was important that the collection was relatable to the viewer. This was achieved by making ordinary objects extraordinary through the carefully-considered, displayed items such as a slogan t-shirt, a lipstick and medication. Scott referred to Jean Baudrillard’s idea that it is ‘oneself that one collects’. The display of the everyday allowed poignant messages about the realities of emotional and physical pain and joy to be expressed, to convey greater understanding to the cis person of a transperson’s personal journey.

One of the most touching comments came towards the end of the day from Tate Britain’s Clare Barlow. A comment card left by a visitor had said, “I think it might be safe for me to come out now.” For Barlow this was a powerful reminder as to why LGBT content in art galleries and museums was paramount for furthering visibility and inclusiveness. These projects, she said, could also be self-exposing and emotionally tiring, so it was important that conferences like Queer Legacies kept momentum going. All presentations were connected by discussion of the need for universal accessibility to the spaces and representations; the need for co-creation through recruitment and participation of volunteers; the need to ensure a legacy through sustained, continued exhibition work; and the enhancement of collections by further acquisitions with LGBT histories.

What I took away from this illuminating conference was the importance of institutions moving away from museums simply as didactic spaces and the need to shift towards a meaningful, interactive dialogue with the public. History is all our histories and there needs to be a halt to it being written by the victors or only by those at the top of the academic hierarchy.