Annie Jones, BA Fashion and Dress History, enters Nan Goldin’s inner world through her recent exhibition.

Nan Goldin is an American photographer who has intimately chronicled her life and the lives of those closest to her since the early 1980s. Her visual autobiographical style has captured the LGBTQ community, the HIV and Opioid crises alongside the fleeting nature of young love. Goldin’s latest exhibition, Sirens, opened at the Marian Goodman Gallery in November 2019 and is her first solo exhibition in London since 2002. In Sirens, Goldin presents new photographic slideshows as well as unseen video and photography work dating back to the 1970s. As an admirer of Goldin’s previous work, such as The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, a collection of photos and slideshows capturing intimate moments of love and loss, which she suitably described as ‘the diary I let people read’, I was elated to attend an exhibition of hers for the first time.

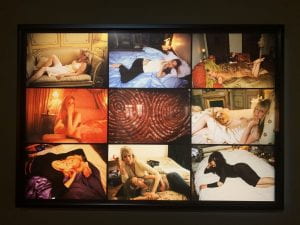

Upon arrival, exhibition-goers were greeted by the hum of music from rooms in the distance; these had long red curtains drawn, blocking out the blaring sounds. Entering gave the air of walking into an underground party or club, which was highly fitting for the subject matter Goldin displays. Images of nightlife, as seen in Figure 1, dominated the walls. They were accompanied by images such as the ones in Figure 2, which focused more on the aftermath of a party.

Goldin brings the viewer along in her journey of documentation. ‘The major motivation for my work’, she once explained, ‘is an obsession with memory. I became a serious photographer when I started drinking because [the morning after] I wanted to remember all the details of my experiences. I would go to the bars and shoot and have a record of my life.’ This made me, the viewer, feel less like an outside witness and more of an extra companion in her intimate moments.

As I followed the music and went behind the curtains, I was greeted by looped videos on screens arranged in triptych. In the centre was a clip from Metropolis, the 1927 film by Fritz Lang, which included a group of men leering, gurning and dropping their jaws. On the right side was a clip of a showgirl dancing sensually, and on the left a scene of disarray and mayhem as the inside of what seems to be a palace is torn to shreds. The installation appeared to represent the power of female sexuality and the chaos that can ensue as a result of its influence. Female sexual power is seen throughout the exhibition, as women are portrayed as strong social beings as well as admirably vulnerable when alone.

The structural aspects of the exhibition heightened its impact. The building was dark, with the only source of light from the street and the back lighting of the photographs. This brought a specific sense of focus to each frame and highlighted the saturated tones of the 35mm images. The photos had no labels, leaving interpretation completely up to the viewer, a choice that suits Goldin’s documentary style. A description of each photograph would have taken away that sense of personal belonging previously stated. It would have merely cemented the images as photographs by a particular person and of a particular place and time. Additionally, as Gillian Rose observes of labels in Visual Methodologies, these can make the artist the most important aspect of the work of art. The most important part of Goldin’s photography is not the artist. What will be of the greatest significance in each piece remains subjective to its viewer. This corresponds to what the art dealer Karsten Schubert described in his 2000 book, The Curator’s Egg, where, he argued, ‘the museum is now much more involved in a two-way dialogue with its audience. It relies more on interpretation and less on absolute truths.’

What Goldin produced in Sirens was honest and insightful. She captured with her camera the emotions of intimate moments, creating a sense of oneness between her, her photographs and their viewers. ‘For me’, she explained, ‘it is not a detachment to take a picture. It’s a way of touching somebody – it’s a caress’. Goldin’s caress puts her subjects at ease; it also created a powerful sense of belonging and comfort within me as I joined in their moments.