Shannon Wilson, MA Curating Cultures and Heritage, reflects on good practice in the museums sector.

A group of MA Curating Collections and Heritage students was recently given the opportunity to visit the Horniman Museum and Gardens in Forest Hill. This trip allowed us to consider how issues relating to access and learning in museums might be addressed in practice. While the wet weather prevented us from enjoying the gardens, we were able to explore many other areas inside the museum. Below, I discuss my impressions of the Natural History Gallery, the World Gallery and the Hands on Base Gallery.

The Horniman Museum attracts a large number of both new and returning visitors, with many families who enjoyed visiting the museum when they were younger coming back with their own children. Upon entering the bright, airy entrance to the Horniman, you are immediately hit by the noise from the World Gallery, which seems to rise up and spill over onto the mezzanine level above it. The gallery that houses the museum’s natural history collection can be found here, although once inside, the atmosphere changes completely as you are met with quiet tranquility and a soothing pastel colour scheme (not to mention the famous Horniman walrus). The pared-down, traditional displays contain many of the founding objects in the museum’s collection and seem to have been virtually unchanged in the past 100 years. The familiarity of these displays and the peaceful environment in which they are situated may be one reasons why so many visitors are drawn back to the museum.

Alongside these well-worn, well-loved exhibits, there is also a relatively new display at the entrance of the gallery about a form of art called Crochetdermy® by the artist Shauna Richardson [Fig. 1]. The small installation includes examples of the artist’s work alongside a collection of graphs and diagrams illustrating the ‘Evolution of the Artist and the Exhibited Works’. While the influence of the museum’s taxidermy displays on the artist’s work is clear, this section’s modern aesthetic stands in stark contrast to the rest of the gallery. This may have been an intentional decision on the part of the curator, perhaps representing the ‘evolution’ of the museum’s display practices as a whole, especially when compared to the contemporary styling of the World Gallery below [Fig. 2].

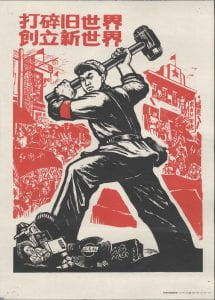

Containing a dizzying 3,000+ objects, as well as a range of video clips and interactive features, the World Gallery is loosely divided into four spaces: an Introductory area, Encounters, Perspectives and Horniman’s Vision. The Encounters section houses collections which represent different ways of living and are further divided by continent: Africa, the Americas, Asia, Oceania and Europe. Although the noise in the World Gallery as a whole can make it quite difficult to concentrate on the displays, this part of the gallery is without a doubt the strongest, most thoughtfully curated and well presented (if a little visually busy).

Conversations with museum staff revealed that many of the display cabinets have underlying themes running through them that determined how each object has been selected and arranged. The Perspectives area is tucked into the very back of the gallery and is designed to encourage visitors to reflect on how and why objects are categorised, and how this contributes to our understanding of the world. This section of the gallery also contains a display about disability and mental illness that was co-curated by the museum’s Access Advisory Group (AAG). It is clear after speaking to members of staff that this display was the product of much hard work and collaboration. The museum adapted certain aspects of its practice to better accommodate the needs of the AAG, such as allowing one member of the group to draw objects using their preferred medium of felt tip pens (which would usually not be possible). However, in practice this display feels almost lost amongst the vast assortment of objects around it, demonstrating some of the difficulties that can arise when translating collaborative community engagement into gallery-based exhibitions.

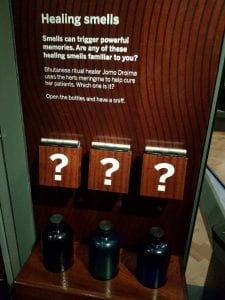

On our MA, Curating Collections and Heritage, we have considered the benefits of multi-sensory display to inclusive learning practice, and the World Gallery at the Horniman makes great use of multi-sensory display techniques. There are things to see, hear, touch and smell, as well as many activities that encourage audience participation, such as the cloutie tree, which is covered in brightly coloured tags bearing messages of well-being and thanks written by visitors {Fig. 3].

There are also opportunities to interact with objects in the Hands on Base gallery. This is a fantastic space, full of objects which can be touched and even worn. During the week this gallery is booked out for school and community sessions, but at weekends and during school holidays there are some free drop-in sessions available for all visitors. The star attraction in this gallery is undoubtedly the discovery boxes. These boxes were developed with a number of groups within the community and respond to a range of themes. For example, ReWrite, a large refugee focused organisation, created ‘a survival kit for landing on a new planet’. While there are certainly some inconsistencies in the Horniman’s public-facing practice which it would benefit from addressing in the future, these discovery boxes successfully celebrate the range of collaborative work that is taking place at the museum [Fig. 4].

Overall the Horniman Museum is a joy to visit and sets a great example for the museums sector. Although the museum does need to be mindful of the potential for sensory overload for some visitors, the bright, stimulating displays are clearly very popular. The museum as a whole is very accessible and there are many different ways to engage with the collections.