In the first of our new series highlighting research in University of Brighton Design Archives, third year History of Art and Design student Lizzie Collinson reviews Elizabeth Wilhide’s book Pattern Design

When one first looks at Pattern Design by Elizabeth Wilhide (Thames & Hudson, 2018), the use of Anna Hayman’s ‘Palmprint’ pattern on the cover (Fig. 1), gives a clue to the splendour inside. From the concise yet poetic introduction, Wilhide’s passion for patterns is evident, leaving a lasting impression on the reader as they continue on through this new publication. She notes patterns’ importance: ‘a pattern’s repeat may be so simple as a regular grid of evenly spaced dots, or as elaborate as a branching design whose diverse elements take time to tease out, where the play of foreground against background is as a complicated as a visual dance…Pattern gives pleasure’. As textile and pattern design is often an overlooked element of design history, her enthusiasm for this genre will undoubtedly influence her audience positively. Pattern Design will certainly interest social historians in addition to art historians, as Wilhide discusses the effects of industrialisation and mechanisation on wallpaper and textiles. The Industrial Revolution conjures images of soot-filled skies and mundane factory work, and so her recognition of the impact of improved technology on pattern production reveals an often overlooked side of this industrialisation.

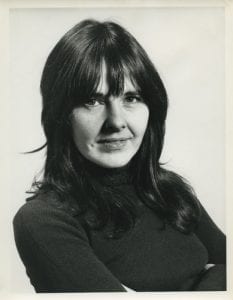

Fig. 2 Marianne Straub, 1972. From the Design Council Archive, University of Brighton Design Archives.

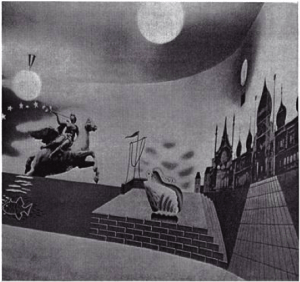

Wilhide draws on many collections, including the University of Brighton’s Design Archives (Figs. 2 and 3), in order to create an encyclopaedic guide of over 1,500 patterns, from eighteenth-century India, to modern day Cath Kidston. Divided into five main chapters – ‘Flora’, ‘Fauna’, ‘Geometric’, ‘Pictorial’ and ‘Abstract’ – the reader, whether an academic or merely someone with an interest in pattern design, is able easily to locate and learn about whatever pattern they choose. The inclusion of non-Western techniques and patterns helps to deconstruct the Western-nature of art and design history discourse that many have become complacent to – the use of an eighteenth-century Sarasa Indian textile produced for the Japanese market is especially interesting, as normally the study of art history focuses on the West’s influence on the non-Western and vice versa, ignoring the interaction between distinctly different ‘non-Western’ nations and cultures.

In addition to specific styles, designs and techniques, art movements such as Art Nouveau and Chinoiserie are described, alongside relevant artists such as William Morris. As a result, Pattern Design is exceedingly accessible, choosing to focus on the skilful artistry and rich history, rather than using the theoretical language that art and design books and journals tend to fall into to, consequently shrinking their possible audience. The effects of pattern design on societal systems and hierarchies do not go unnoticed by Wilhide. She commends women such as Enid Marx and Sarah Campbell for their works’ influence on contemporary design.

The thematic rather than chronological ordering allows comparisons to be made between the past and present; this approach is rather refreshing considering the chronological categorisation art and design historians are more than accustomed to, particularly in gallery and museum spaces. Pattern Design is, deliberately, primarily visual and neatly ordered so that one can dip in and out at leisure. Although it is clearly factual, it is a highly pleasurable read.

Elizabeth Wilhide’s Pattern Design was published by Thames & Hudson in 2018. Find out more about the University of Brighton Design Archives here.