BA (Hons) History of Art & Design student Kitty Symington reports on a course visit to Tate Modern

This winter sees the Tate Modern holding an extensive exhibition through eleven rooms consisting of Albers’ work throughout her career, from her beginnings at the Bauhaus, to her experimental pictorial weavings, through to her metaphorical ideas about material and craft. It’s a well-deserved and beautiful commemoration to such a highly influential figure in the world of textile design and modern art, and the second year History of Art & Design students were lucky enough to visit it during our Modernism module. As we entered the first room of her stimulating exhibition we were immediately confronted with Anni Albers’ giant creature of a loom. As one of the leading innovators of the Bauhaus school of the early twentieth-century, she set out to combine the ancient technique of traditional hand weaving with the abstract language of Modern design.

Fig.1. Anni Albers, Black White Yellow ,1926, re-woven 1965, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Joseph and Anni Albers Foundation, Tate.

A design of Albers’ that particularly interested me was one she first produced in her early Bauhaus career in 1926; it is the large wall hanging called Black White Yellow (fig.1). Here, Albers used only black, white and yellow threads, despite the appearance of multiple hues in the piece. This technique – one that she continued to use throughout her life – consisted of using different combinations of each of the colours on the warp and the weft of the loom to produce a complicated but complementary language of a variation of colours.

Albers’ initial watercolour drawings displayed in the exhibition allowed us to understand the development of her ideas: from the complex mathematical preparations on paper, through to the incredible finished products hung on the walls. Her work is, arguably, easier to appreciate once we are aware of her extensive processes; personally, I admired Black White Yellow more after considering the intellectual methods behind its alluring designs.

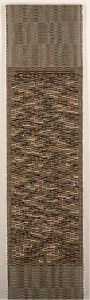

Fig.2. Anni Albers, panel from Six Prayers, 1966-7, The Joseph and Anni Albers Foundation, The Jewish Museum, New York.

After Black White Yellow, Anni produced a considerable collection of intricate experimental weavings. We were shown a vast sensual array of colours, textures, materials, free-flowing patterns and extravagant techniques involving the play of light and transparency. A project that was exceptionally striking was a piece called Six Prayers from 1966-7. The Tate describes it as Albers’ most ambitious pictorial weaving, both for its metaphorical emphasis and its technical advance. Albers was commissioned by the Jewish Museum in New York to create this memorial piece to the six million Jews that died in the Holocaust. We learned that the six panels represented the six million and that, as Albers herself was from a Jewish family, the commission must have struck deep with her (fig.2 shows one panel of six). The form of the panels visually takes on the form of Torah scrolls; the complex woven patterns of the threads sculpting the delicate appearance of Hebrew scripture in a sombre manner.

Fig.3. Anni Albers, Intersecting, 1962, The Joseph and Anni Albers Foundation, New York, Tate Modern, London.

This piece illustrates the incredible affect that Albers’ designs have had on their viewers throughout the twentieth-century, and certainly the Tate’s glorifying exhibition of her career provokes such feelings today. All-in-all this exhibition was an inspirational one, and one that teased the senses; possibly the only drawback of the Tate was that we were unable to touch the beautiful textures with our grubby fingertips.

Anni Albers continues at Tate Modern until 27th January 2019.