What do a cigarette packet and a rubber duck have in common? MA History of Design and Material Culture student Sarah-Mary Geissler explains

1: FLOAT: Atlas of the World by Andrew Ward, 1997, and This is to announce the publication of Liver & Lights nos. 16, 17 & 18 to be collectively known as Triptych by Liver & Lights, 1994.

St. Peter’s House Library Special Collection, University of Brighton.

One is an innocent bath-time toy, the other a monument to vice. One has a sleek, smart design, the other cartoonish and animated. One is juvenile, the other adult… I could go on. The point is that they’re just not very similar at all. So how could they possibly be connected? Not only are they both objects but, technically, they are both books! The two may be the last thing you expect to find in a library, though both indeed have shelf marks and can be found in the University’s library catalogue.

The duck is an artist’s multiple; objects commissioned in limited editions but often with a subverted meaning. As well as the duck, the box includes a card containing diagrams showing how to arrange the duck (or several) within a bathtub to indicate different countries. Hence the title, FLOAT: Atlas of the World. Andrew Ward created these in 1997, at a time where Young British Artists such as Tracey Emin and Damien Hirst were selling their own customised everyday items as accessible works of art.

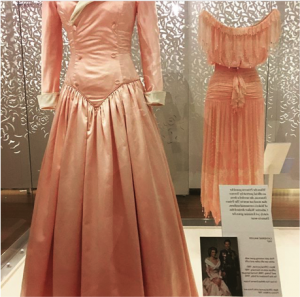

The cigarette packet was produced in 1994 by the artistic collective Liver and Lights, and contains a rolled-up scroll. This ‘book’ is a catalogue for upcoming magazines complete with prices, postage details and a cut-out subscription form. The magazines were No.16-18, the Triptych, and the ‘bookworks’ were published in a shoebox.

3. This is to announce the publication of Liver & Lights nos. 16, 17 & 18 to be collectively known as Triptych, cigarette box and scroll.

The classification of ‘book’ encourages the viewer to read the object and consider what visual cues the artist intended. Should information be confined to pages? Does a book require a cover? How involved can a reader be? Design is a creative answer to everyday problems, and these objects question how we understand the everyday.

Neither object was designed explicitly for their current purposes – they were repurposed by the artist. The reader cannot help but imagine Andrew Ward bulk rubber duck shopping, and wonder whether chain smoking each box empty counts as artistic intervention?

S.Geissler1@uni.brighton.ac.uk