Becky Kearney (MA Design History and Material Culture graduate, 2013) on her PhD research

In 2011 I started the Design History and Material Culture Masters course at University of Brighton, drawn by its strength in the field of dress history. Now I am in the first year of a collaborative PhD at the University of Kent and the Science Museum, funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council (AHRC) researching false teeth from 1848–1948. Many people, not least myself, are surprised by this seemingly large leap from dress to dentures. In this blog post I discuss my experience of moving from design history to medical history and the benefits of a collaborative doctoral partnership (CDP).

Fig 1. Claudius Ash and Sons Manufactory, Kentish Town. Etching. Image printed in A Catalogue of Artificial Teeth and Dental Materials Manufactured and Sold by Claudius Ash & Sons’, (London: Claudius Ash & Sons, 1865). Wellcome Collection.

During the Masters course at Brighton my interest in clothing worn on the body shifted to items incorporated into the body, such as hair extensions or prosthetics. When I read on a park billboard that Kentish Town, London was allegedly the world’s largest supplier of artificial teeth in the nineteenth century, it piqued my interest (Fig.1). I found grotesque photos of early eighteenth-century teeth made from gold, ivory, porcelain and human teeth and it convinced me these objects were worthy of further research (Fig.2).

Fig 2. Partial upper and lower denture, with springs, lower of ivory, repaired, upper of swaged metal, by Gabriel, with platinum tube anteriors and ivory posteriors, 1856-1880. Full view, white background.

Predominantly, dental historians have written the histories of artificial teeth from a technical and innovation-centred perspective. However, key themes within the objects’ history such as craft practices, commodification and body modification are common to the disciplines of design history and material culture. Denture-makers in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries often came from professions such as jewellery or watchmaking. Early porcelain teeth-innovators purchased the pastes for the porcelain from the famous decorative ceramics company Wedgwood and, by the late nineteenth century, employed mass manufacturing techniques akin to Wedgwood to produce them, making dentures widely accessible across Britain.[i] Early twentieth century advertising material issued by dentists or quacks, promoting artificial teeth and their associated transformative qualities, also had parallels with a burgeoning cosmetics industry. A design history of the denture was possible.

Three years after completing my Masters, my former MA supervisor, Annebella Pollen, made me aware that a funded PhD on false teeth had come up; it was too good an opportunity to miss. The AHRC funds many collaborative doctorates each year, bringing universities and museums or other institutions from across the UK together, in my case: the University of Kent and the Science Museum, London.[ii] CDP students are given access to the museum or institution’s collection for object research, they receive training, supervision from a curator and may have the potential to get work experience within the museum. The AHRC itself also offers training, funding, and a community of other PhD students to collaborate and socialise with. The Design History and Material Culture masters at Brighton encouraged my interest in object-based research through its own teaching collection and in engaging with museum archives so this type of PhD has felt like an ideal progression.

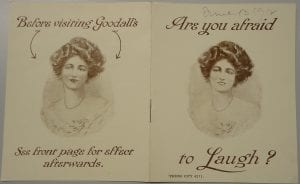

Fig 3. Goodall’s Institute dentist card from Swanson Collection of dental advertising material EPH646, Wellcome Collection. Archive. Personal photograph.

At Kent University I have encountered the entirely new field of the history of medicine, with very different subject areas, proponents, archives and conferences to design history. There is, however, much more in common than at odds between the two departments I have studied within. Material culture is increasingly being applied to the history of medicine and will be the core methodological approach in my thesis about the Science Museum collection. Fields such as the history of emotions have previously been interrogated by medical historians but have only very recently been brought together within material culture.[iii] Both departments promote a highly interdisciplinary approach as well as drawing from a multitude of sources from archival to oral history. Most notably both the Brighton and Kent faculties consist of an energetic community of lecturers and researchers pursuing diverse research interests that, however seemingly disparate to my own research, frequently offer inspiration, context or relevant conceptual frameworks.

The niche field of oral health has led me into contact with sociologists, literary, medical and dental historians, curators of medicine, as well as practicing dentists. The increasingly interdisciplinary nature of academic research may result in entering unfamiliar fields, leading to what one lecturer at Kent has described as a feeling of ‘imposter syndrome’. However, the consensus amongst my Kent History department colleagues is that pushing the boundaries of one’s immediate field and engaging with interdisciplinary research, although sometimes intimidating, when executed well can be highly rewarding and has the potential to reach many more people.

[i]R.A Cohen, ‘Messrs Wedgwood and porcelain dentures correspondence 1800-1815. I. De Chemant, Thomas Byerley and others, 1800-1812,’ British Dental Journal139(1975): 27 – 31. R .A Cohen, ‘Messrs Wedgwood and porcelain dentures correspondence 1800-1815. I. De Chemant, Thomas Byerley and others, 1800-1815 II. Joseph Fox, Thomas Byerley and Robert Blake, 1810 – 1815,’ British Dental Journal 139 (1975): 69 – 71.

[ii]AHRC collaborative doctoral partnerships 2018. http://www.ahrc-cdp.org/phd-studentships-list-of-ahrc-collaborative-doctoral-partnership-phd-oct-2018-start/

[iii]Example of the history of emotions and material culture see: Stephanie Downes, Sally Holloway and Sarah Randles (ed.). Feeling Things. Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2018.