The ART/DATA/HEALTH project aims to work with communities and citizens to build their digital and data science skills in order to understand large amounts of data – and the way we do this is through creativity and the arts. The COVID-19 crisis has released a large amount of data about infections and deaths worldwide, and understanding what these data mean is essential for influencing public behaviours, such as self-isolation and social distancing.

This is not just my view: it is shared by groups now active in the COVID-19 crisis such as the #data4covid19 initiative. The Data Stewards Network advocate for

BUILDING CAPACITY. They say:

“Governments should increase the readiness and the operational capacity and maturity of the public and private sectors to re-use and act on data, for example by investing in the training, education, and reskilling of policymakers and civil servants so as to better build and deploy data collaboratives. Building capacity also includes increasing the ability to ask and formulate questions that matter and that could be answered by data. Such a list of priority questions and metrics could facilitate more rapid response by critical data holders.”

From my point of view, as the project lead of the ART/DATA/HEALTH project, I also find it important to address other skills:

- First, citizens need digital skills that help them to spot misinformation about the spread of the COVID-19 virus, which gets circulated online. The public needs to be able to tell what is credible information and what not (see next Resource blogpost).

- Second, now that many of us are asked to work remotely, we are signing up to new teleconferencing tools – but there are quite a few data privacy concerns, raised by organisations such as the Electronic Frontier Foundation. How can we work and connect with friends and family remotely during COVID-19 while keeping our personal data safe? (see next Resource blogpost).

It is hard to grasp the impact of the coronavirus on a local scale, especially when the threat seems “distant”, or affecting “others”. This difficulty is exasperated with the “keep calm” attitude, which has resulted to significant delays in implementing measures, especially here in the UK. How can data science help us understand the COVID-19 situation better?

VISUALISING KEY INFORMATION

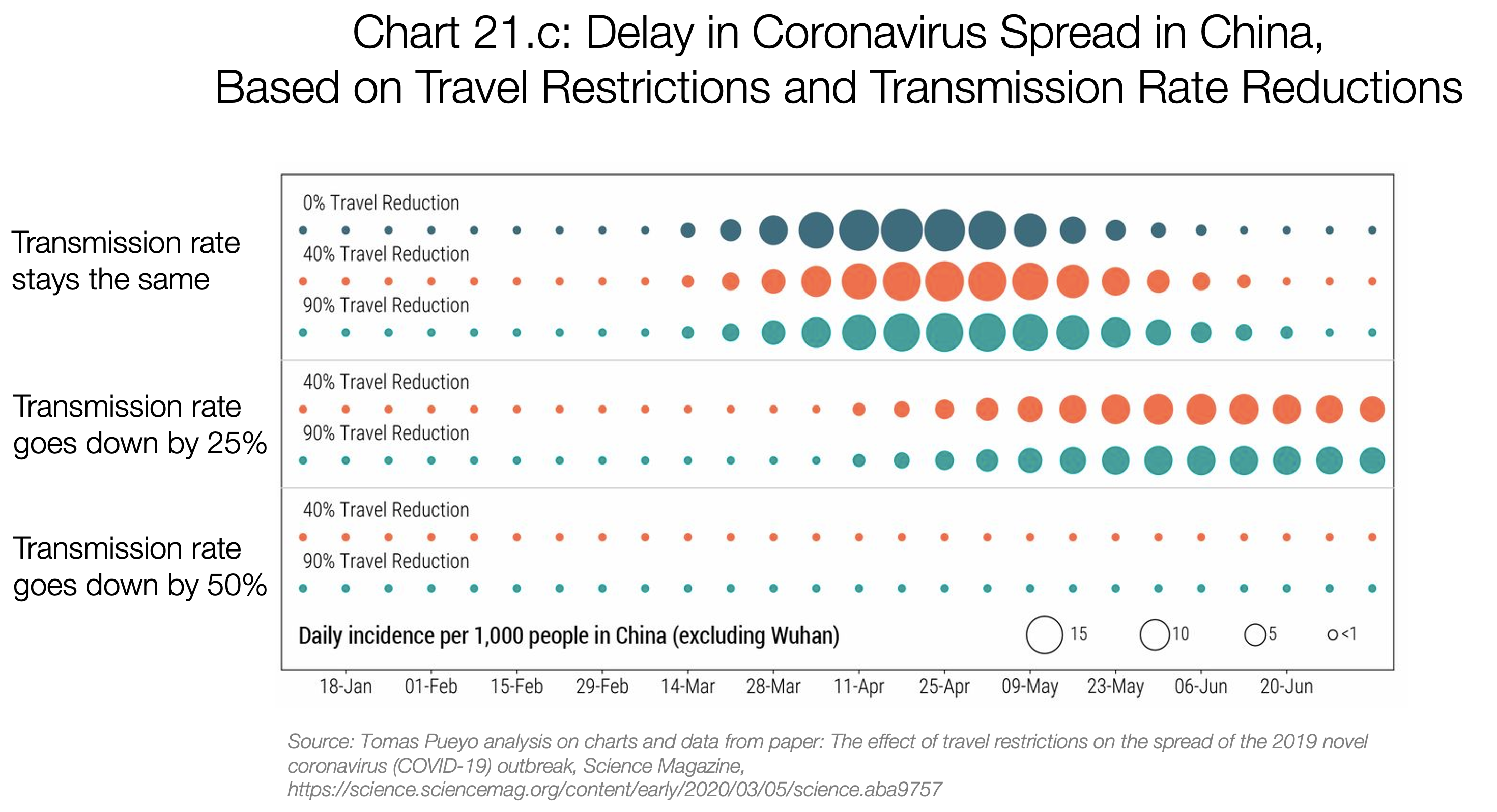

One way in which data science is currently being used is to provide key information with simple visual and simulations. The Medium article written by Thomas Pueyo on 10th March 2020 (and updated) received 40 million views in a week and was translated in over 30 languages. The article contains tons of useful information and lots of graphs, which audiences will have got used to seeing in social media in the last month already. Pueyo made some data visualisations himself on the effect of travel restrictions, which shows clearly the decrease of transmission rates.

MODELLING

Another key way that data science is used however is for modelling the spread of the epidemic and to advice public health and officials on important decisions, for example on closing schools or research funding for a vaccine. For example by mid-January, one group of data scientists had circulated an analysis listing the top 15 cities at risk of the virus spreading, based on airplane flights and travel data (Greenfieldboyce 2020).

The Washington Post model visualisation that was shared extensively in social media as the key to understanding social distancing shows a simulation of people depicted as dots. It shows changes of count of the recoverd, healthy and sick over time, but interestingly it does not depicts deaths. (Stevens 14 March 2020)

Looking at simplified visualisations like this is useful, but we should be reminded that modelling is exactly that: modelling. It cannot provide accurate predictions; it can rather provide indications that might be useful for policy makers to get their head around potential future scenarios. This because the quality of available COVID-19 data is poor: “Right now the quality of the data is so uncertain that we don’t know how good the models are going to be in projecting this kind of outbreak,” says Marc Lipsitch, an epidemiologist at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.(Greenfieldboyce 2020).

In order for data science to be effective in informing and advising decision makers and citizens however, models and modeling tools, and data that underpin these decisions should be made openly public. This will allow both experts and citizens to scrutinize such decisions. As the Open Data Institute (ODI) CEO Jeni Tennison notes

“the models governments are using are more sophisticated than the Washington Post model. They are based on evidence about other epidemics, and data about this one. They might take into account factors like how long after infection people become contagious, when they start showing symptoms, and how long they are contagious after they recover; different levels of social mixing by different people; and people’s compliance with instructions.”

The #data4covid19 initiative has been developed to put pressure for more openly distributed data, so that these data can be used by scientists in a systematic and sustainable way during and post crisis. The initiative aims toward building data infrastructures that are key to being prepared to tackle pandemics and other dynamic societal & environmental threats in the future (TheGovLab 16 March 2020)

The group bring the example of how mobile phone data were used in the Ebola case, and how Facebook data were re-used to understand public perceptions around the Zika virus in Brazil, and so on.

A wealth of projects have responded to the call to build an infrastructure for data-driven pandemic response. These projects are listed to “show a commitment to privacy protection, data responsibility, and overall user well-being”.

You can see a repository for data collaboratives seeking to address the spread of COVID-19 and its secondary effects here.

—————————————————–

Note 1: In the blogpost Covid-19, your community, and you — a data science perspective, published in fast.ai on the 9th March 2020, Jeremy Howard and Rachel Thomas made some resources available in 18 languages, in order for people to understand the impact of the virus on their local communities.

“The number of people found to be infected with covid-19 doubles every 3 to 6 days. With a doubling rate of three days, that means the number of people found to be infected can increase 100 times in three weeks (it’s not actually quite this simple, but let’s not get distracted by technical details).”

The post also explains the difference between logistic and exponential growth.

“Logistic” growth refers to the “s-shaped” growth pattern of epidemic spread in practice. Obviously exponential growth can’t go on forever, since otherwise there would be more people infected than people in the world! Therefore, eventually, infection rates must always decreasing, resulting in an s-shaped (known as sigmoid) growth rate over time. However, the decreasing growth only occurs for a reason–it’s not magic. The main reasons are:

-

Massive and effective community response, or

-

Such a large percentage of people are infected that there’s fewer uninfected people to spread to.

Therefore, it makes no logical sense to rely on the logistic growth pattern as a way to “control” a pandemic.”

Note 2: One example of how this is being taken up is a modelling exercise, which provides graph visualisations for staying at ‘home’ households, and households that they categorise as ‘moving’.

The “home,” household “stays in their house, receives deliveries of food or other necessities, and practices social distancing (6+ feet) if they go for a walk outside. They make decisions like whether to order take-out, whether to treat Amazon or Instacart type deliveries with dilute bleach or let non-perishables with hard surfaces sit for 2 days, etc. They also decide whether to go see their “best friend” once every 10 days.” The Moving household A “moving” household is a household where one or more people in the household have a job where they move around in the community. This includes people who are delivering food, bagging or boxing food in distribution centers, police, firemen, doctors, nurses, grocery store workers, and so forth.

*Featured image-top of page: “The-Ecology-of-Disease” by Olaf Hajek-Illustration