The Archive of Willy de Majo Pt. II

After the initial sort out of the de Majo archive in our external storage unit, the next step in the process was for all of the materials to be transported to The Keep for conservation. We have a good, collaborative working relationship with The Keep’s conservation department, which is an invaluable resource for us. Personally, after I finished my PgDip at Camberwell in 2011, I volunteered for quite a while in the conservation studio with The Keep’s Paper Conservator Melissa Williams when her conservation studio was housed at The Maltings in Lewes. But I digress.

After transportation, the first step was to place all of the materials in the quarantine room. This is to ensure any possible mould and other issues materials may have are contained within one enclosed space. From here, fellow paper conservator Kristy Woodruffe and I began the process by taking one box at a time as we tried our best to not become overwhelmed by the sheer volume of materials.

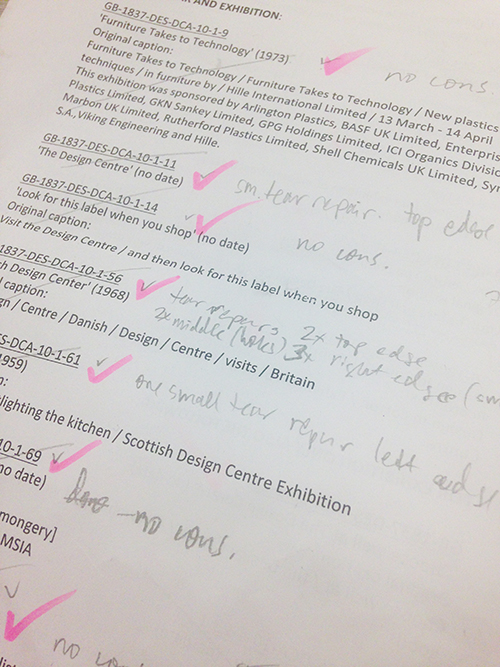

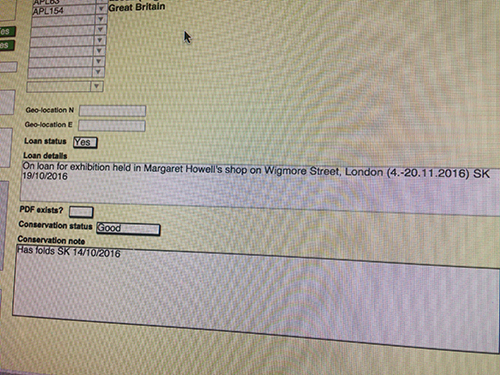

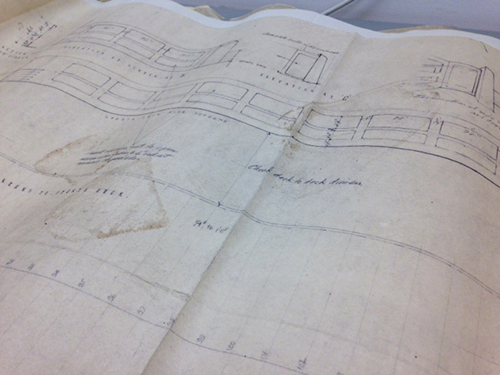

We went through the materials in this manner, sorting them in an order discussed with our Archivist Sue Breakell as we went along. Every single item was surface cleaned using a museum vacuum – I dread to think how many individual pieces we ended up vacuuming in the end! Documentation records listing contents of the boxes and bundles were filled in for all batches of materials to ensure we were keeping tabs on everything at all times.

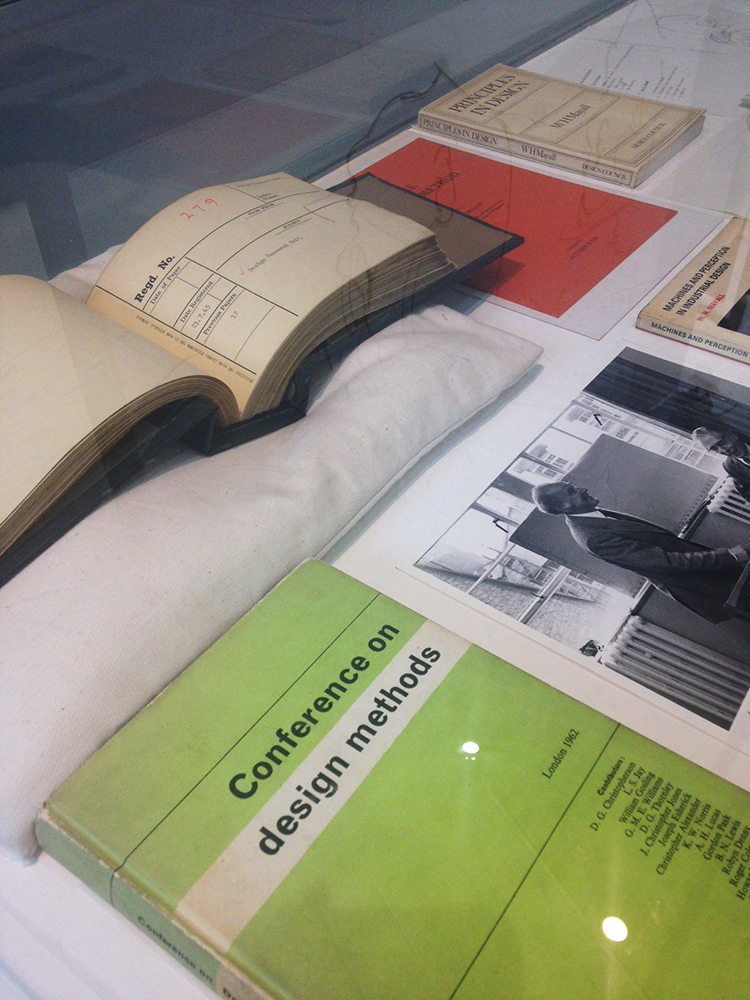

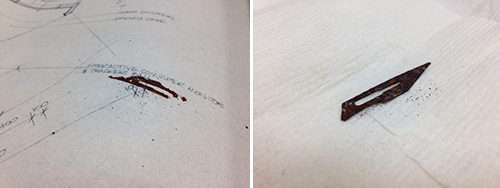

During this initial sorting and cleaning process, we also had to make sure we were thorough in separating photographic materias, foils, paper with fugitive inks and other ‘non-standard’ materials unsuitable for the freezer from everything else. Items falling under those categories were packaged separately with clear labels to enable them to be reunited with the packets from which they were originally taken. I thought I would show you some of the delightful/strange/beautiful things that could not be put through the freezer as we found some treasures! Like these beautiful pieces with watercolour vegetables on the left and fugitive inks on the right:

And these wonderful pieces from materials relating to Letts. They are a company responsible for inventing the world’s first commercial diary over 200 years ago. We came across, amongst many other materials, a watercolour skater for their Skateboard Diary 1980 and sheets of transfer images which originally came with a diary.

One of my favourite pieces has got to be this simple piece on the left of Willy de Majo practising his signature. We also came across a signed card from the movers and shakers of Icograda from the 1980s within the wealth of Icograda material also present in de Majo’s archive. He was, after all, a founding member of the organisation, which we hold the archive of here in the Design Archives. Both of these items had fugitive inks present and were therefore not suitable for freezing.

There were also some other more unusual materials we had to keep an eye out, like these mirrored squares and a strip of metallized Mylar within the stacks of correspondence materials.

Amongst the correspondence we also have letters from Saul Bass to Willy de Majo, which have Bass’ rather brilliant signature stamp – this also popped up as an embossed version on his letter-headed papers. I personally adore it!

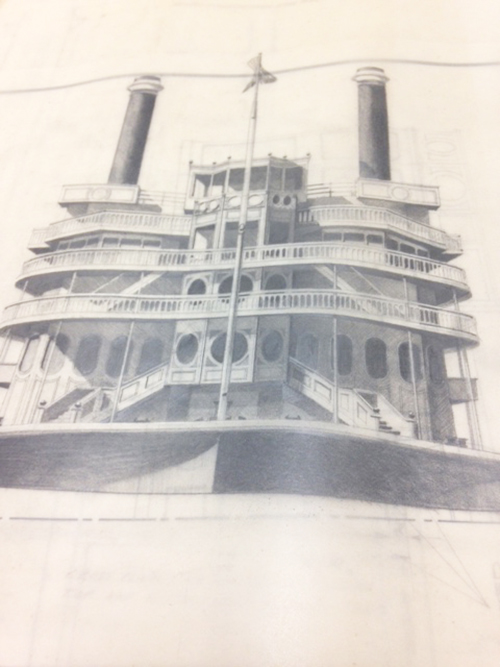

In the client papers, there are various beautiful original pieces of artwork for the various commercial clients de Majo had, like this one for Ronson. It is drawn with ink and painted with watercolours with various collage elements adhered on. Again, not one for the freezer, this!

I could show you an endless stream of visually striking items from the archive, but I will stop here! There is obviously a lot more depth to these materials than just ‘beautiful things’, but I simply couldn’t stop myself from taking some photographs along the way of the most scrumptious pieces.

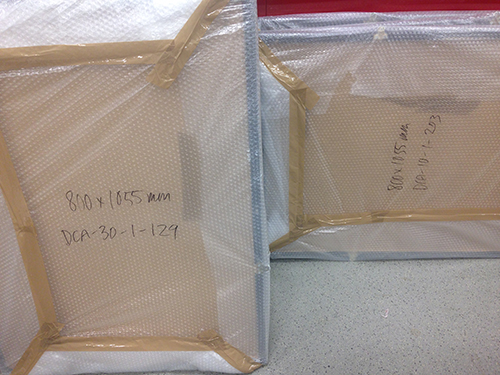

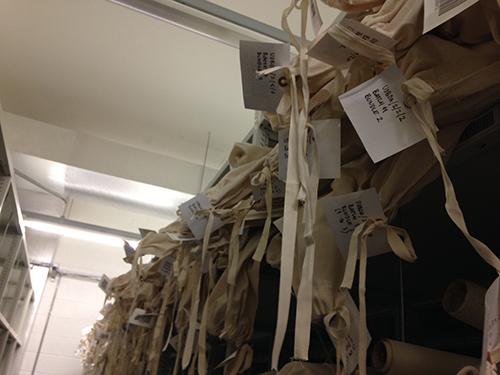

Once all the materials unsuitable for the freezer were separated and packaged, the freezer-friendly paper-based and bound materials were placed in vacuum-bags in clearly labelled batches.

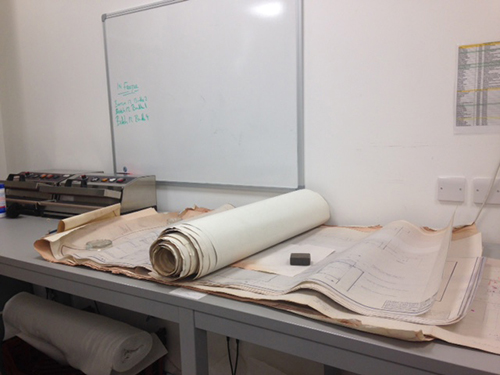

The freezing process takes place in special conservation freezers which take the temperature down to -35c very quickly – I have mentioned the Keep’s freezers ‘Jen’ and ‘Brian’ in a previous post about Gardner’s rolled up plans. The purpose of this process is to dry the materials and prevent mould growth, which it does very efficiently. Mould growth can already occur within 2 to 3 days of being exposed to moisture, which is a terrifying thought when dealing with big volumes of materials. The papers were left in the freezer for seven days, after which the packs were opened, materials were taken out and laid out vertically to air-thaw for a week.

After this, we were able to lay the materials out in the conservation studio, as opposed to working within the quarantine area. We were able to perform a further sort for the materials that needed to be together for boxing purposes. The boxes were clearly labelled and numbered for transportation back to the Design Archives HQ, where we made space for the large volumes of materials descending upon us.

To get to this point, the process for the de Majo archive already took several months of hard work with a work-schedule of two days a week. Sometimes it amazes me what you can achieve when a team of people works together like a well-oiled machine – makes everything so much more enjoyable despite it looking like a daunting task when you start!

I will be adding to this story as and when time allows, so do keep your eyes peeled for Part III…