Read Attila

- Attila 1 pdf

- Attila 2 pdf

- Attila 3 pdf

- Attila 4 pdf

- Attila 5 pdf

- Attila 6 festival issue pdf

- Attila 7 pdf

- Attila 8 pdf

- Attila 9 pdf

- Attila 10 pdf

- Attila 11 pdf

- Attila 12 pdf

- Attila 13 pdf

- Attila 14

- Attila 15 pdf

- Attila 16 pdf

- about issue 16 and a reading of an article by its author Davy Jones 35 years after publication

- Attila 17 pdf

- Attila 18 pdf

- Attila 19 pdf

- Attila 20 pdf

- Attila 21 pdf

- Attila 22 pdf

Erratum and update on the Attila article:

30/08/2017 Paul Kaczmarek is a Brighton-ian who can be heralded for his actions as a member of the anti-fascist movement in sixties and seventies Brighton. He bought The Little Red Schoolbook from Bill Butler’s Unicorn Bookshop and handed out copies to in his class. A self-described teenage nuisance freak, he knew Bill from 1968 until his death.

Paul is currently writing a book about Bill Butler and Unicorn Bookshop called Poetry, Publications and Prosecutions. It’s to be followed by Bill’s complete works.

Paul located these archives which retain Bill Butler’s poetry, letters, and certain collected objects. A lighter from Morocco with a unicorn on it stands out as a valuable keepsake. Paul remembers Bill and has steered me, Lisa Redlinski, through a couple misconceptions I had about Bill Butler and Unicorn Bookshop.

Paul’s generous corrections:

Bill didn’t write Attila on his own – he was responsible for much of the first few issues, but it was always a community effort.

I wrote a couple of items and provided some news, and I know at least a dozen others who did the same. Issue #8 has a list of most of the people who contributed, at least 5 of whom worked for Unicorn. ‘Rick’ in the list was Rik Wilkins, a big burly biker with a fierce Viking beard and a gentle laughing stoner temperament. He did almost all the mock-up and printing work for Attila and most of the other duplicated publications between late 1970 and early 1972 on the ancient smelly machinery upstairs at the shop.

Bill moved to Brighton from London, not the West Coast of the USA. He was in SF during at least 1955-9, and haunted the famous/infamous City Lights Bookshop there, where he met Ginsberg, Kerouac and the rest of the Beats. Bill kept a lifelong contact with a number of them – Ginsberg performed a reading at Unicorn. From there Bill went to Greece in late ‘59, where he taught English and worked on a traffic scheme for the authorities, went back to SF and published his firt book early 1960, then moved to London sometime late 1960 – the records are very sketchy on dates before 1962.

While in London, as well as having a number of weird jobs he was involved with most of the alternative literature scene, and in 1965 managed the paperback section of Better Books, the classic early 60s alternative literary bookshop in the UK. He left them in early November 1965 and moved to Brighton, where he was a bookrunner for about a year before setting up Unicorn Bookshop, which opened Summer 1967. Can’t give precise dates, but letters addressed to Bill at his permanent address 12 Over Street, Brighton (just across from Unicorn) exist from 12.11.1965, the first Unicorn letters or invoices date from early August 1967.

Unicorn opened Summer 67 to November 1973 (it’s not certain whether the end of October according to his friend Professor Eric Mottram’s diaries – or beginning of November as mentioned in a 1974 letter from Bill). I’ve not quite finished analysing Bill’s letters, but can’t see getting any more precise about the dates. Bill didn’t keep a diary as such, the main way of tracing some dates is through his draft poem books.

After closing, Bill wound down in Brighton over a couple of months – still selling by post until December, then the business moved to a farm in Wales February 74, where Unicorn kept publishing and distributing books until early 1977. He moved back to London early 1977, Unicorn wrapped up June 1977, and Bill died in October.

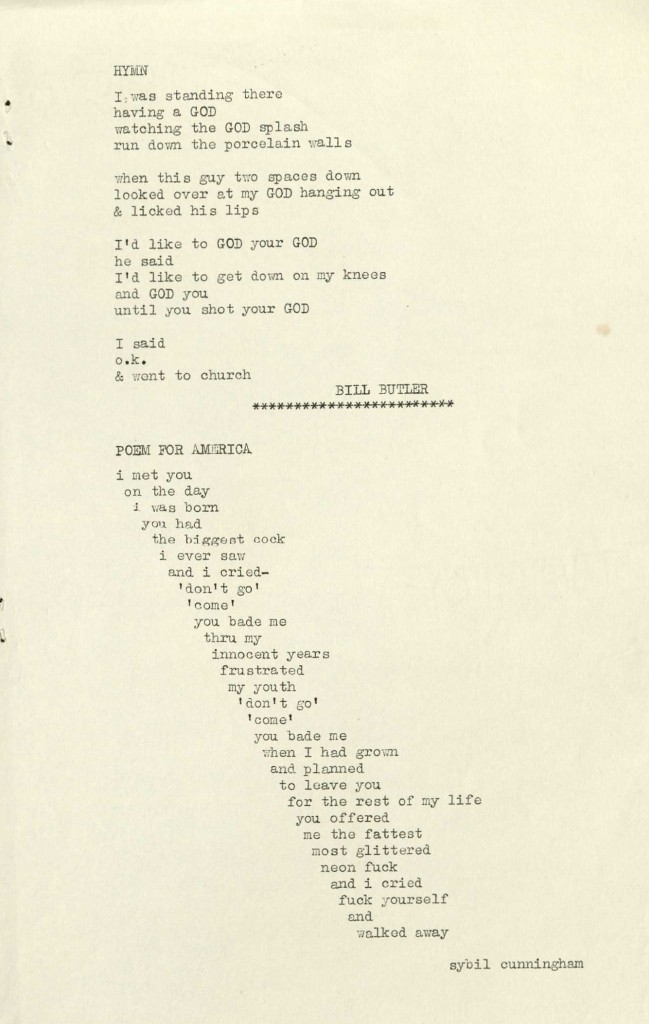

I think the page from Brighton Head and Freak magazine containing Bill’s poem ‘Hymn’ must be issue #3, which was issued in 1969. I don’t have complete copies of BH&FM, but #3 is the only one I’ve not yet established the contents of from the photos (Bill was only in #3 and #5, and mentioned in several others).

I’m still trying to work out if BH&FM was printed by Unicorn. You probably know, but just in case … it was edited by John Upton, who designed the famous Unicorn fascia, but rather complex for Unicorn to deal with, with cut-outs, stick-ons and all sorts of visual trickery – no two copies were the same

As to the bust (16.01.68 for the record), it’s a commonly held error that Unicorn was fined for the Ballard ‘Why I Want To Fuck Ronald Reagan’. Three copies due to be sent to Anne Graham-Bell, literary agent at Penguin Books and a friend of Bill’s, were among the 3,500 seized items, but the prosecution dropped this part of the case near the end as they were in a sealed package on Bill’s desk in the shop. The prosecution had to acknowledge they could not demonstrate they were ‘for sale for commercial gain’ so the law didn’t apply.

Now the original article as written by Lisa Redlinski —

Bill Butler is the writer, editor, printer and distributor behind Attila. His nom de plume was Attila, and he played with his pseudonym referring to himself as Attila the Hungry, or Attila the Honey. Reading every Attila I could lay my eyes on, Attila the Honey comes across as playful, sweet and intellectual. I’ve dreamt about Bill, a gorgeous sensual man eager to introduce and guide you through the esoteric in Brighton. He’s an important person in the history of Brighton and maybe my favourite.

He moved to conservative 1960s Brighton from California’s West Coast as a young man, and he brought a bit of the Height-Ashbury hippie haven to this Victorian Riviera.

Butler opened Unicorn Bookshop at 50 Glouster Road and ran THE unofficial community service alongside his licensed bookshop for its six years of operation. Budding hippies, freaks, radicals and left-y youth in Brighton sought out Bill and Unicorn staff to talk literature, politics, sexuality (Butler was openly gay), parties, the psychoactive and esoteric and much more. His presence here changed the political map of Brighton by nurturing a progressive population, one which persists until today as a counterpoint in an otherwise perpetually conservative South Coast.

He was easy to find in print or in person. Generous, he shared his writing and his time freely and published in several local papers. This page of his poetry is taken from Head and Freak Magazine circa early 70s

Attila, Unicorn’s weekly mimeo community paper, published the writing, illustrations and organsing efforts of Brighton’s alternative movement. Butler produced and wrote the first 21 issues. Calls for group members, revelers, road trips or alternative services are in every issue.

The June 12th 1971 issue Attila lists:

- a pre-festival frolic at Churchill Square

- a Freer Streets carnival for quiet streets [without car traffic noise]

- a Revolutionary Festival at the University of Sussex

- contact information for the allotments officer along with advice to invoke Pan, Silvanus, Ceres, and The White Goddess for your patch of veg

- times for the prohibited student radio show Radio Albatross

- hours for a new vegetarian restaurant Open Sect on 7 Victoria Road

- times for Sussex Festival and Worthing Festival

- Gonczar’s home address for those interested in joining UFO-watchers club.

Butler was a coordinating force for the alternative people of Brighton. Deeply moral, he cherished civil liberties. From the first issue of Attila he speaks on behalf of their protection. Furious about the obscenity charges levied against the countercultural paper OZ, he argued that the moral politics of British institutions were corrupted and not, as they claimed, the morals of the alternative communities.

“One good liberal witness has refused to testify on the grounds that he personally finds the material (Skoolkids OZ) “DISGUSTING”. Which wasn’t the point. The law doesn’t say anything at all about what makes you sick to your stomach — like the Archbishop of Canterbury makes me sick to my stomach. That, alone, doesn’t make him obscene.”

Martin Luther King famously said “The ultimate measure of a man is not where he stands in moments of comfort and convenience, but where he stands in times of challenge and controversy.” Brighton had Butler to grow its good witnesses. Butler’s need for people to argue against arbitrary censorship came from hard lived experience. Unicorn Bookshop was raided by the police in January of 1968; Butler was prosecuted and fined for selling copies of Evergreen Review and J.G. Ballard’s Why I Want to Fuck Ronald Reagan.

Like anyone who wants to nurture people into taking responsibility for fellow human beings, Butler prompted people to live according to their morals. John Spiers excellent bibliography of underground press quotes Butler challenging his peers.

‘What alternative? Where is the much talked about “community”? Is the community your clique or ours? Was there any action last summer/were there any actual alternatives which weren’t purely for the coffee-table freaks?

‘If you’re quick to blame the “average freak in the street”, a safe well-used assumption, bear in mind that the real apathy has its source not in the streets but in the … half-a-dozen so-called “community shops”, none of which provide an alternative service. . .

…’Nobody has ever touched the problems of finding different ways of working in this town…There are no alternative means of earning enough to live on, or of finding different means of shelter.

…Admit that at the present level of activity the very word community does not help, except to stoned dreams and coffee-table, rush mat gossip. Are you a psychic leach?

Today, in stark contrast to the hippie/freak/alternative/radical messages of self-determined futures of irreverent joy, there’s a conservative stronghold which dominates in our public discourse. Trump, Brexit, and the massive killing off of public services under the Cameron cum May government are examples of how a conservative worldview can successfully fabricate an elaborate system of moral justifications for unpopular, possibly even cruel, policy choices. Incidentally, when Reagan ran for presidency in 1980, Why I Want to Fuck Ronald Reagan was mockingly circulated at the Republican Party Convention.

It’s Reagan’s presidency that marks the beginning of a conservative worldview that would spread through political, media, academic and religious institutions. Reading Butler we can ground ourselves in a history of Brighton’s grassroots progressive instincts, and a discourse to inspire us to coordinate our efforts to lead public opinions (as progressives did in the 60s and 70s) rather than follow them.