Max Gill conservation – day 1

Day one of the two days of conservation scheduled in with myself and paper conservator Melissa Williams is now behind us. The work was delivered to the conservation studio on Friday and we started working on them early this morning and by the end of the day had a very respectable percentage of them done. We made a decision to start with the ‘easier’ pieces – these were categorised as such due to the fact that Design Archives’ volunteer Suzie Horada had surface cleaned some of them prior to getting them in the studio and others that were generally in great condition.

From the pieces we worked on today I thought I would highlight a few things that needed to be taken into consideration while working, first of which is a great example of being aware of what is at the verso of the objects.

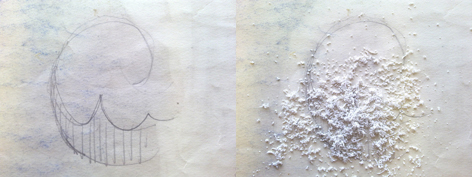

The image above is the from the verso of Max Gill’s ‘Cable & Wireless Great Circle’ map – a watercolour original from 1945. The recto was mechanically surface cleaned with a sponge due to the fragile nature of the watercolours, but the majority of the back could be cleaned with a block of rubber – apart from the areas in which Max had ‘sketched’ with a pencil. First I cleaned around the area as close to the pencil marks as possible with a block of rubber. After this I used grated rubber to clean up over and around the sketched area to make sure that removal of the sketch itself was minimised. The results from this method won’t look as ‘clean’ as using a block or more solid piece of rubber but considering not much pressure can be applied to a pencilled area when surface cleaning, using grated rubber (or a sponge) is a very effective method.

Pencil marks are not the only thing you can come across on the reverse of objects that need to be taken into consideration when cleaning items. Below you can see an example of the verso of one of Max’s unfinished pencil and ink pieces for the Glasgow Empire exhibition of 1938. In this one his pencil marks on the recto were so heavy that they had created these beautiful indentations on the verso – special care needs to be taken in cases like this as these areas should not be flattened by applying too much pressure. This would lead to losing all this detail and despite the fact that they can be found at the back of an item, the ‘information’ is just as important and often just as interesting. In these instances, the best way to mechanically surface clean is to use a sponge and go over the areas carefully.

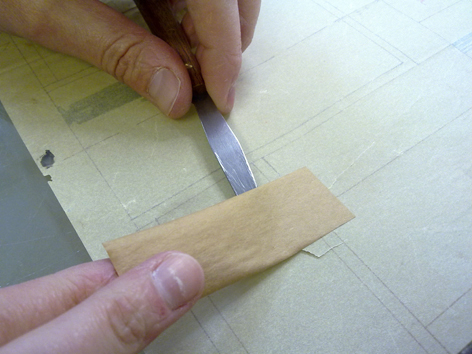

Two of the original artwork pieces we worked on today had tears in them ‘repaired’ with magic tape. As the adhesive used in tapes like this is not good for the condition of the paper in the long run, the tape pieces were carefully removed with the help of a hot iron and tweezers. The tears these pieces held together were then repaired with heat-set tissue, which is not only very easily reversible but much more sympathetic to the originals as they gain age.

In cases where a piece had a small corner missing, one was ‘created’ for them. This is done by repairing as much of the corner from the verso of the piece, but also adding a smaller piece of heat-set tissue on the recto of the object, as close to the edge of the tear to minimise visible repairing.

Another item worth mentioning is a watercolour piece on tracing paper, entitled ‘Plans for Ship building’. This had been repaired by using brown tape pieces at the verso to hold together several tears along the edges of the object. This type of tape is similar to the one used by David Cooper in the final framing of the objects – the tape has one side that becomes tacky when wetted. In this instance, the tapes appeared to be relatively old ‘repairs’ as the nature of them was dry enough to make the removal of them relatively easy to perform with a small spatula. All of the tears were again repaired from the verso using heat-set tissue.

A couple of the pieces also appear to have silverfish damage. These are little silvery crawling creatures that have been around for 400 million years and are usually a symptom of moisture problems. Silverfish feed on a lot of human foods but also create destruction with paper products, glues, starches, sugars and even fabrics. Silverfish prefer darkness and the ideal conditions for them to flourish are at 75-95% relative humidity with temperatures between 21-26c. On paper, silverfish do not like inks and in a lot of cases they will destroy paper around any inked areas. Damage from silverfish usually appears very irregular and notched and the size (ie the coating) of the paper has been grazed.

This particular Gill item has now been repaired from the verso with heat-set tissue to avoid further damage and rips to the effected areas.

Despite the hectic nature of today, I am very much looking forward to tomorrow and getting on with the more ‘complex’ objects from the exhibition selection being conserved by myself and Melissa.