Alfred Fairbank, calligrapher

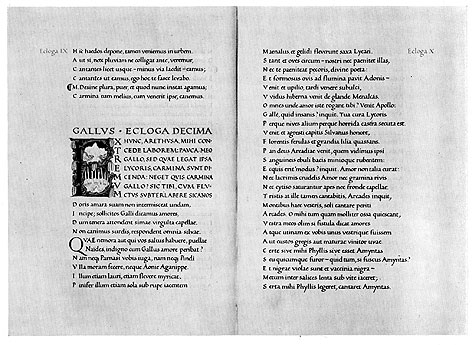

A well-known calligrapher and leading advocate of handwriting reform, Alfred Fairbank taught at Brighton College of Art from 1955 to 1966. A civil servant at the Admiralty for more than 30 years, he developed his calligraphic interests by visiting the Victoria & Albert Museum in his lunch hour to view manuscripts by William Morris, Palatino and Graily Hewitt. He was also inspired by Edward Johnston’s Writing, Illuminating and Lettering (1906). A founder member of the Society of Scribes and Illuminators in 1921, Fairbanks enlisted in part-time classes at the Central School of Art and Design, studying under Graily Hewitt. Fairbank worked closely with illuminator Louise Powell over a 13 year period that included his manuscript book Ecclesiasticus (1926-9), commissioned by the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge. In 1928, he was commissioned by Monotype to produce the compact typeface known as Narrow Bembo. In the 1930s May Morris presented Fairbanks with a highly-influential loan of one of Wiliam Morris’s prized possessions, a crimson leather-bound volume of four Renaissance writing manuals. Fairbanks’ prolific output included his landmark Book of Scripts, a King Penguin (1949) designed by Jan Tschichold. In the 1950s he studied palaeography and wrote many influential books, founding the Society for Italic Handwriting in 1952

As his Brighton colleague Margaret Hortpn wrote: “In 1955 Alfred retired from the Admiralty to live in Brighton and work at the College of Art as lecturer and adviser. Until 1966 his tall figure, stooping a little from years of calligraphy, could be seen on special days moving punctually and deliberately up the hill to the Teacher Training Department, in his hand a net bag holding some precious book or manuscript to share with the class. His sayings and axioms became apocryphal: ‘Handwriting is a system of movements involving touch’; ‘Handwriting is a dance of the pen’.”[1]His Dryad Writing Cards (1935), articles such as ‘A Graceful Cure for the Common Scrawl: A Fair Italic Hand’ (1955) and his nine Beacon Writing Books (1959) were further testimony to his commitment to handwriting reform, as was his development of the first italic pen nib. “At his Memorial Service his best friend said, ‘Not only was he one of the finest calligraphers of our time but there was given to him that rare chance to turn a personal activity into something far-reaching…. He eventually turned his scriptorium into a world·wide movement for the reform of handwriting.’[2]