The university has given many names and many structures to its creative arts departments, but ask any Brighton taxi driver for the ‘Art College’ and it’s like some long-lost friend’s been waiting too long. That was my experience when coming to work at the Polytechnic in 1984 — ‘Polytechnic?’ they said baffled. So I set off on foot to explore the tangled North Laine before working outwards into a spacious Old Steine. Here I found the columned facade of Grand Parade rubbing shoulders with a fruit and vegetable market on the one side and oriental minarets atop a nearby Royal Pavilion on the other. I would have been speechless, on that first day, if anyone had said the next twenty-two years of my working life would be spent there. But they were with every moment turning out to be as rewarding as it was testing. It was time spent amongst colleagues working in a very special academic community, through a period of substantial change in higher education, that I count as a great privilege.

Poster exhibition on the theme FACE, Brighton School of Art Archive, The Design Archives. RIGHT: ‘Art from Zimbabwe’ poster, 1994. Brighton School of Art Archive, The Design Archives.

My move from East Anglia to East Sussex, in 1984, was stimulated by a chance encounter with John Vernon Lord who was then Head of Graphic Design at the Brighton Polytechnic. In his other role as chair of the national CNAA board for graphic design, John had participated in a review visit to the Norwich School of Art where I was his equivalent Head of graphic design. I also still worked as a design consultant and was pondering a full-time return to this. Shortly afterwards both John and I were members of a CNAA visit to the Harrow School of Art. When the meeting was over we found dinner at an Indian restaurant in Lambs Conduit Street and shared our respective thoughts on educational management and professional practice. In this conversation John indicated that he too had relinquished the role of Head of Department to find more time for the teaching and production of illustration. Otherwise I only now recollect the “salmon fish curry” we both ordered and plates sinking under whole fish smothered in curried sauce. Something must have been said, though, as I ended up applying for, and being appointed to, the post of Head of Graphic Design in Brighton after it had been filled by Tony Cobb for a short period.

My new job coincided with the moment when things started to change and the post-industrial world, with its associated knowledge economy, was ushered in. This said, the new mobile phones still resembled bricks and Apple Macs appeared on our desks like bulky-grey-shoe-boxes. Indeed, one of my first tasks was to address the massive changes being brought to our printing industries by this first-generation of digital tools. In this context our decision to transfer City and Guilds courses in printing to the Brighton College of Technology was the beginning of a long-standing relationship that still stands.

Departments up and down the country began to dump the older metal technologies in favour of less space-hungry digital systems, believing they were moving into a gleaming age of post-industrial production. Against this trend we resolved to both preserve the older metal systems and absorb the emergent digital technologies. In retrospect this was a good decision based on an unproven instinct that, for students, the embodied knowledge gained from a physical engagement with materials would always be essential to their effective manipulation in digital form. Consequently, David Igglesden and John Packers’ good stewardship of the letterpress and bookbinding workshops ensured the preservation of first-class resources that still stand — and Faith Shannon’s certificate courses in bookbinding were, in their time, superior to the best master-classes found anywhere.

Maria Rivans, Tension star brooch, 1986. The Aldrich Collection.

To explore the seeming dichotomy between traditional crafts and the digital technologies of this, emergent, post-industrial culture we forged a link with Rediffusion Simulation then based at Gatwick Airport and world-leaders in the field of real-time image-simulation. I had previously met one of their developers, John Vince, at the Middlesex Polythechnic where he pioneered the integration of computer imaging systems into art and design practice. Financial support from Rediffusion, and John’s expertise enabled us to initiate the Rediffusion Simulation Research Centre led by Colin Beardon (1991). Over the years this provided a base for the work of colleagues such as Suzette Worden, Sue Gollifer and Chris Rose (with its first conference also seeing the inception of CADE — Computers in Art and Design Education (1995)). Work in the Centre went on to demonstrate, amongst other things, that the relationship between traditional craft and new technology could be symbiotic — with fresh insights being brought to the nature and importance of craft in a digital age.

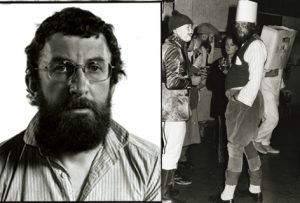

LEFT Portrait of Sean Hetterley. RIGHT Pottery party image with John Vernon Lord

A precursor to this new Centre had been a conference organised by Evelyn Goldsmith in 1986 entitled ‘Electronic Design in the Graphic Arts’ with publicity designed by Maggie Gordon (her poster affectionately redefining the conference as “can pigs can fly?”). Taking some interest in this event the then Polytechnic Director, Geoffrey Hall, suggested that Ranjit Gill from our IT department be invited to speak. It was one of Geoffrey’s many significant interventions for, to everyone’s surprise, Ranjit talked of the relationship between humans and computers and the dignity of craft — this at a time when computers were largely producing shiny, spinning, facile graphics. Evelyn’s own work had stimulated much debate too. Her research into illustration produced the 1984 conference ‘Research in Illustration: 2’ and a monograph also titled ‘Research into Illustration: an approach and a review’ (CUP, 1984). Located in a department of world-class illustrators such as Alan Baker, Raymond Briggs, John Lord, Chris McKewan and Justin Todd, Evelyn’s research was both pioneering and controversial.

Teachers in the department included George Hardie and Gerald Woods, whose co-authorship of Art Without Boundaries produced a text as necessary as Ways of Seeing and Design for the Real World. Clive Chizlett, Harold Cohen, Miriam Goluchoy, Maggie Gordon, Philip Miles and Don Warner directed the teaching of graphic design and both Liz Leyland and Jeff Willis followed each other to lead it at the Royal College of Art. Roland Jarvis taught charcoal figure-drawing to everyone, Andrew Restall brought a painterly approach to illustration, Tom Buckeridge masterfully developed photography without ever leading a course and Geoff Trenemman produced fine books with Gerald Woods. Within such a diverse group of passionate teachers the assessment debates could often be lively. Once two colleagues were debating the award of a first class honours mark — one challenged the other to explain why it was justified and they exclaimed, in all sincerity, ‘because it gave me an uplifting experience’. This seminal moment, in which one person’s uplift was another’s disappointment, led us to develop shared assessment criteria within a common framework well in advance of the QAA audits of learning and teaching yet to come (in 1999 art and design was to receive a score of 22 and in 2001 humanities a maximum 24).

Around the same time we also developed a new Masters degree in Narrative Illustration and Editorial Design (c. 1987) that was unusual in having a thematic base at its intellectual core. Building on the faculty’s traditional strengths in narrative and storytelling it offered a learning experience in sequential communication that crossed disciplinary boundaries.

In 1987 the Great Hurricane ravaged Brighton. I vividly remember the scene — on walking down to the faculty that next morning after the storm — where once graceful trees lining Grand Parade now lay across the road as if pushed down by some massive hand. More than twenty years after this event, and looking back on the memory, I find it comforting to again see that part of the Old Steine outside our faculty populated by trees grown tall and foliage in the Grand Parade quadrangle matured. Had we known then what was in store for higher education this stormy assault may have seemed the first harbinger of change.

Between 1984-89 my fellow Heads of Department were John Crook, Robert Haynes, Gwyther Irwin and John Miles with Gwyther being replaced by Bill Beech and John by Roy Peach. As the 1980s drew to a close and the 1990s commenced we all began to sense the change in climate. Resources came under pressure and the massification of higher education emerged along with the first signs of an audit culture. Our dean of art and design, Robin Plummer addressed this changing landscape with a conference entitled Brave New World in which the emergent agendas for Higher Education could be explored ahead of time. Indeed, Robin’s long and distinguished career had been characterised by such insights along with significant contributions to the development of art and design education nationally. Amongst many other innovations he brought performing arts and humanities into the faculty, supported pioneering work in the history of design, laid the first foundations for research and improved the governance of examination processes and created a new post of Faculty Officer in the university and then appointed Andy Durr to the said post.

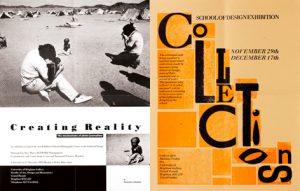

Poster for Creating Reality exhibition. Brighton School of Art Archive, The Design Archives. RIGHT: Poster for Collections exhibition (2004). Brighton School of Art Archive, The Design Archives.

Andy’s career had started as a technician on the Foundation Course and then moved on from faculty officer to lead adult education courses and teach history. His further involvement in local politics, first as a ward councillor then Mayor of Brighton (2000-2001), was instrumental in bridging our relationship with the local community. His work to rejuvenate the seafront, between the Palace and West Piers, included space in the arches for a Brighton Polytechnic research centre entitled the Fishing Museum (1999). The centre’s aim was to conserve oral testimonies of the seafaring families in East Sussex and amass a body of historical material connected to the fishing community that still forms a permanent display in the museum. Other than space provided to set it up funding was limited and I recollect many Saturdays spent with a hammer and saw helping to build the museum’s interior. Around the same time Frank Gray initiated the South East Film and Video Archive (1992). The historical materials he and his team discovered shed new light on the life, customs and dress in Sussex after the advent of moving film. These two initiatives, together, made a significant contribution to our relationship with the local community to be followed by the creation of other cultural festivals including CineCity (2003), Visions and the Brighton Photographic Biennal.

On Robin Plummer’s retirement the post of dean went out to national advertisement — I applied for it and was appointed with a starting date of September 1989. That time managing the Faculty was to be punctuated by significant changes brought to higher education over the next fifteen years. In 1989 I also joined the art and design board of the Polytechnics and Colleges Funding Council to witness the first steps taken to increase student numbers in higher education and massify the system. In this emerging climate — and for the ten years between 1990-2000 — many faculties of art and design within the polytechnics did not fare so well — being perceived as either too expensive, space hungry, just troublesome or some combination of all these inconveniences. Some limped along, others closed, some merged and a few were valued. Even at this distance I find it hard to explain why art and design at Brighton continued to flourish and prosper throughout such a turbulent period. Nor can I identify any specific individuals or linear sequence of events that might have been responsible for this — the process was, at times, messier and more creative than any neat answers might suggest though the objectives were always clear and the effort collegial.

The faculty’s physical location may have been an important ingredient. Enjoying perhaps the most attractive arts campus to be found anywhere in the UK it often is described as an art-school-by-the-sea. Located right in Brighton’s cultural quarter, opposite the Royal Pavilion, with a quadrangle garden that is the perfect green lung, its near distance from the main university site ensures both belonging and independence. Another important ingredient (alongside this near physical coherence) is the historical foundation on which art and design traditions at Brighton are based (and which this book sets out to celebrate). A continuous stream of development since the art college’s inception in 1859 had served to create a very strong sense of collective identity, and the awareness of what it meant to be an art college, that would always be present — even to this day. This could easily have evaporated in 1970 with the art college’s incorporation into a new Polytechnic — but the influence of its Director, Geoffrey Hall (1970 – 1972), and dean of faculty, Robin Plummer (1974 – 1989), were crucial at this pivotal moment in time. Geoffrey supported and promoted art and design within the new institution, as did Robin who also built a vital bridge between its traditional practices and their rightful place within the new academy.

Professor Bruce Brown, author of current text, Dean of the Faculty of Arts 1987-2008

In 1989, I did not think of art and design faculties as places full of like-minded individuals being tightly managed, but spaces where intellectual and creative worlds could rub shoulders with each other in meaningful and sustained conversations. Nor did I perceive research in art and design as either peripheral or formulaic but something that could lead to unpredictable and surprising results — and was a vital ingredient in the learning experience of both students and staff alike. Indeed, I felt that the intrinsic spirit of enquiry so redolent of research could be a key driver in developing the learning environment. My challenge was to lead and manage all of this and to leave it alone when needed.

In this context we first established a unified framework that helped to facilitate exchanges between the strong set of core disciplines already constituting the faculty. Three new Schools of cognate subject groupings were created from the existing set of departments along with a common academic framework between them (1994). Robert Haynes moved into a faculty role as academic planning co-ordinator (to develop and implement the new academic framework), the new School of Art was led by Bill Beech (until 2003) and the School of Design by Roy Peach. The Headship of a third School of Historical and Critical Studies — incorporating the departments of Humanities (still located at Falmer) and Art and Design History (located at Grand Parade) — was put to advertisement and Peter Widdowson appointed. Shortly afterwards this new School of Historical and Critical Studies was co-located in premises at Pavilion Parade, opposite the Brighton Royal Pavilion, near Grand Parade. The School of Design was later to be led by Jude Freeman and the School of Historical and Critical Studies first by James Horne and then Paddy Maguire. When architecture and interior design returned to the faculty the schools of Art and Design were reshaped. The new School of Architecture and Design was led by Anne Boddington (1998-2006), and the School of Arts and Communication first by Bill Beech until his retirement in 2003, then Karen Norquay. Later, in 1998, courses in fashion and textiles in the Finsbury Road annexe were relocated onto the Grand Parade site within their new School of Architecture and Design.

Alice Fox (Louella and Alice), work in Inclusive Arts Practices with Rocket Artists

Around 1994 the adult education classes were extended into a credit-rated Saturday Art School that offered the local community greater access to HE. This provision had always been an essential and equal part of the faculty’s work alongside undergraduate teaching and research. Recent years have seen the extension studies programme developed into an award winning Access to Art project led by Alice Fox as part of the Community University Partnership Programme. Undergraduate course development was also stimulated to see the inception of new degrees such as Editorial Photography (1991). This evolved from high quality photographic work being undertaken across a number of courses within the faculty. Karen Norquay led the development with teaching staff that included Iain Roy from the department of art and design history and Mark Power who had been a student of illustration in the 1970’s. To make space for this new course, and concentrate the faculty’s core provision, it was decided to relocate the existing Foundation Course, then housed in the Circus Street annexe, to the Brighton College of Technology where it has continued to flourish and grow. Other course developments have included Masters degrees in Inclusive Arts Practice, Materials Practice, Cultural and Historical Studies, History of Design and Material Culture. New Bachelors degrees included Design for Production, Performance and Visual Art, Digital Music, History of Decorative Arts and Crafts and Screen Studies.

Alongside these activities a research investment fund was inaugurated. This allowed staff to bid, competitively, for resources to support their research. In 1990 this initiative was two years ahead of the first, national, Research Assessment Exercise (RAE1992) and so provided the sound footing that led to an award of grade 4 —the university’s highest quality grade in the first of these successive RAE’s (the grades being 1-5 with 5 highest).

During these times the staunch support given by a range of friends and sponsors was to be a further, important, ingredient. Principal amongst these were the Aldrich and Edwards families. When, in 1994, one of the potential efficiency gains under consideration was to cut spending on the annual student degree exhibitions we responded by employing a professional fundraiser to source potential sponsors and write letters inviting their involvement. I seem to remember the work cost a flat fee of £250 plus 3% commission on any sponsorship won. Within two days we had three takers and a sole offer from Kenneth Edwards of the Brighton-based solicitors Burt, Brill and Cardens — this we accepted with some relief and gratitude. This sponsorship deal, under the leadership of David Edwards, both saved the degree exhibitions and allowed them to grow in scale and ambition with each successive year. Now attracting circa 15,000 visitors overall, they last a week, have school visits, entertainments and a fashion show. Around the same time Michael and Sandy Aldrich instigated an annual fund to enable the purchase of artworks from the degree exhibitions as well as from previous teachers and students — this historic collection has grown to become the Aldrich Collection. Michael and Sandy also supported the publication of major exhibition catalogues such as Grace Robertson’s A Sympathetic Eye, John Vernon Lord’s Drawing Upon Drawing and the anniversary book celebrating the art college.

ArCade poster. Brighton School of Art Archive, The Design Archives.

In the mid 1990s Colin Beardon and his colleagues in the Rediffusion Simulation research centre noticed that the nationally funded government scheme Computers in Teaching Initiative (CTI) had not included the art and design disciplines. As a consequence they lobbied for a national centre to be set up, won the case, and successfully bid for the new CTI in art and design that was then located at Brighton. Suzette Worden was its first director (1996-1998) followed by Sue Gollifer. In the same period we established a Student Learning Centre under the leadership of Linda Ball and Pauline Ridley (until 1999) that, along with the CTI, helped to lay the ground for a successful bid in 1999 to host the newly created, national, Subject Centre for Learning and Teaching in Art, Design and Media. This then operates from Brighton under the leadership of David Clews who followed its founding manager, Linda Drew.

In 2004 another, major, competitive bid of £5m was won to create a Centre for Excellence in Learning and Teaching through Design led by Anne Boddington and managed by Anne Asha. This operates in partnership with the Royal Institute of British Architects, The Victoria and Albert Museum and the Royal College of Art. Building on the links already established between teaching and research it looked to public institutions as sites of learning alongside universities — especially institutions, such as museums, where objects are a primary source of knowledge. Funding from this initiative also enabled development of the Grand Parade site to include refurbishment of the Sallis Benney Theatre and the creation of a garden-level restaurant and cafeteria. Along with the earlier demolition and rebuilding of Glenside in (1996-1998) these projects brought significant improvements to the Grand Parade campus. Rewarding though it was in 1996 to see the first bulldozers move in to demolish Glenside, many colleagues mourned the ransacking of its infamous basement in which so many illustrious bands, such as Echo and the Bunnymen and the Clash, had performed in their early careers. Once the new building was finished though, and a new entrance created on Grand Parade, the original terracottas that graced the first art college on this site were reinstated and another piece of history restored.

Early success in the 1992 Research Assessment Exercise had been repeated in 1996 with an increased number of staff being awarded the same grade 4. From this point onwards plans were made to improve performance in the forthcoming RAE, scheduled for 2001, so that the greatest number of researchers could achieve the highest quality grade. A Centre for Research and Development was created under the expert leadership of Jonathan Woodham. This included a Research Student Division and the development of specialist scholarly resources in support of research. In 1998 there had been only a few registered PhD students that, in the ten years to 2008, grew to 70. Frank Gray continued to lead the creation and development of important archival resources in film and video and Jonathan Woodham and Catherine Moriarty in design. The University of Brighton Design Archives now hold a collection of materials equal to the best of their kind in the world that include those donated by the UK Design Council, the International Council of Graphic Design Associations, the International Council of Societies of Industrial Design and individual designers such as FHK Henrion, Anthony Froshaug and James Gardner. Jonathan had also established a major research partnership with the Victoria and Albert Museum in collaboration with their head of research Paul Greenhalgh (1997 -). This included the creation of a research office within the V&A and appointment of Jane Pavett who went on to research and create major exhibitions at the V&A such as brand.new (2001) and Cold War Modern (2008). Exhibitions in the faculty gallery at Grand Parade also stimulated research through curatorial projects including, for example, A Common Tradition: Popular Art of Britain and America by Andy Durr and Helen Martin (1991), Alan Davie: quest for the miraculous by Michael Tucker (1994), Makeshift by David Green (2001), Dream Traces: a celebration of contemporary Australian Aboriginal art by Michael Tucker (2003), Fashion and Fancy: the Messell family dress collectionbyLou Taylor in collaboration with the Brighton Museum and Art Gallery (2005), and Memory of Fire: war of images and images of war by Julian Stallabrass (2008).

By the time RAE 2001 came around the faculty was able to make a single, integrated, submission of seventy-four researchers that achieved the award of grade 5. The funding stream, following this recognition of high quality, turned out to be 68% of the universities total income for publicly funded research. This success more than closed the financial gap that opened in 1992 providing sufficient additional resources to support research investment across the university.

The results of the RAE 2008 confirmed Brighton as one of the leading centres for research in the creative and performing arts and humanities. All these activities across learning, teaching and research were developed within a spirit of international cooperation. For example, long-standing contacts established by Lou Taylor with institutions in Central Europe led to a major EU TEMPUS award connecting staff and students in Brighton with their counterparts in Poland, Hungary and France. Contacts in Japan, originally made by Chris Rose, led to the inauguration of a long-standing student exchange programme with the Nagoya University of Arts and Music (1996-). Recent research contacts with the National University of Korea in Seoul have won British Council funding to support further exchanges. Included in these co-operations have been student prizes given to graduating students in each of the institutions. Year-on-year our degree shows have been enhanced by the award of such prizes, in person, by colleagues making the journey from Japan and Korea especially for the ceremonies — often in traditional dress. International co-operations such as these gave many students the opportunity to experience cultural shifts that were a life enhancing experience.

Brighton College closed, 1968. Photograph submitted for public use on University of Brighton alumni web pages.

Media representations of art schools in the 1960s caricatured them as wayward and difficult entities, either in constant states of flux or instability, or challenging the status quo. Caricatures such as these persisted into the 1990s, first as the Polytechnics emerged then as the post-94 universities searched for new identities. It is an irony, therefore, that as many institutions branded and re-branded themselves beyond any form of decent recognition the arts schools remained elements of stable continuity — turning out to be anchors in these shifting sands of higher education. Far from holding a trenchant disregard for changing times this persistence and preservation of the art school traditions into late twentieth and early twenty-first century education, in some universities, has been a real success story.

Celebrations of the Brighton College of Art’s 150 years, in 2009, aligned with the 17th anniversary of Brighton’s inauguration as a new University and my 25th year in office. With these landmarks in mind, and the ability to look back over a quarter century, I would say that the very best traditions of art school education have been preserved and evolved into a university culture operating at the highest level. It is a real success story resulting from a collegial institution, supportive Vice-Chancellors, Directors, Principals and Deans along with the work of a vibrant, colourful and challenging academic community (of which there are too many important and influential individuals to mention in this short essay). Looking back over the last 150 years and into the future I would predict, with some certainty, that this success is set to continue and that it will remain a sustainable endeavour. The recent appointment of Catherine Harper as head of the School of Architecture and Design, Anne Boddington as the new dean of the Faculty of Arts and Architecture and Julian Crampton as the University’s Vice-Chancellor will assure this.

I have many fond memories of my time as dean — of generous individuals, testing colleagues, good parties, vibrant degree shows, loyal supporters and talented students. If I were allowed one symbolic memory of what it sometimes felt like to be the dean of the faculty then it would be connected to Tony Wilson’s drawing field trip to the Somme battlefields in the late 90’s. His students had collected various relics that included spent shells and grenades. These were exhibited along with the students’ drawings in a spot-lit glass case standing in a narrow corridor outside my office. Engrossed in work I was only distracted by the sight of a strange man in large padded jacket, crash helmet and very large gloves gingerly, and silently, carrying some object away. He didn’t notice me or bother to say that the whole building had been evacuated as one grenade was thought to have its fuse intact.

Chapter text, Bruce Brown

Leave a Reply