Introduction

Ditchling, a small East Sussex village by the South Downs, located between Haywards Heath, Lewes, Brighton and Hassocks, is an unusual place. Dating back to Saxon times, it is a community proud of its long history and its continued attractiveness to tourists, who come to see its beautiful setting, the brick and flint buildings and churches[1]. Yet visitors are also attracted by another aspect of Ditchling’s history. The village has been over many decades the location of an arts and crafts community, the legacy of which is still clear, for example, in Ditchling Museum[2] and in the prominently positioned silversmith’s shop[3] in the High Street. It is a combination of traditions that has fascinated many, including resident filmmaker Luke Holland, who produced five documentary films about Ditchling, ‘A Very English Village’ in 2005.

The arts and crafts community of Ditchling was not established merely from the arbitrary preference of certain artists for a creative rural retreat, although this certainly seemed to contribute to their choice of the village as a place to settle and work. When sculptor, wood engraver, type-designer and letter-cutter Eric Gill came to Ditchling in 1907, he was fuelled by a vision of the kind of life he wanted, and by a set of religious, moral and aesthetic values that underpinned his practice as a craftsman. A number of other artists and craftspeople, informed and inspired by the same ideas, followed Gill’s example. Gill himself grew sceptical about the community’s worth and left in 1924, and there has been much debate about Gill’s personal morality and activities[4]. Yet the arts and crafts community he initiated, and which continued to develop and grow after his departure, had a rich and important role in the history of the village.

In the context of the 150th anniversary of the Brighton School of Art celebrated in this book, Ditchling has a further relevance; several of the artists and craftspeople based there since the beginning of the twentieth century have also been students and tutors at the School of Art. The impact of Ditchling is complex: its arts and crafts community has in many ways been very self-contained, and it cannot be assumed that Brighton School of Art students have been highly conscious of it as a reference point or resource in their education[5]. Yet the influence of Ditchling artists and craftspeople within Brighton School of Art as a whole has been significant. The sharing of ideas, transfer of skills and nurturing of new talent was characteristic of many Ditchling artists and craftspeople, and those who taught at Brighton had an important role in the cross-fertilisation of methods and approaches. Equally, the School offered a source of artistic fellowship for those who taught here, creating colleagues and friends within and across the disciplines.

This chapter goes on to highlight some of the connections between individuals and describe the roles they occupied in the development of the Brighton School of Art. In the extract from silversmith Dunstan Pruden’s So Doth the Smith, for example, it is possible to see how students such as Gerald Benney, subsequently a renowned silversmith in his own right, gained invaluable development and mentorship from a tutor who was also a practising craftsman, experimenting with technique and regularly receiving and fulfilling commissions. The landscape painter Charles Knight benefited greatly from the education he received at the hands of Louis Ginnett [6]: both lived in the village of Ditchling for a substantial period of time, and both taught at Brighton School of Art and in Ditchling itself. In her chapter about Fashion Textiles at Brighton, Professor Lou Taylor’s reference to the Ditchling arts and crafts ethos in weaving shows how the tradition was still very much in evidence in the 1970s, even if it seemed to the students and younger staff somewhat at odds with the fabrics, designs and styles current at that time. Through such examples it can be seen that the proximity of the arts and crafts community in Ditchling, and its particular contribution to practice-led education, is an important part of the Brighton School of Art’s history.

The Arts and Crafts Movement and Ditchling

Ditchling is sometimes depicted as an ‘Arts and Crafts’ village, a description that needs to be unpacked and set into context in a number of ways. The group of artists and craftspeople who lived and worked there over the course of much of the twentieth century[7] was strongly influenced by the ideas and ideals of the Arts and Crafts Movement, a phenomenon which was as much ethical and social in nature, as aesthetic. It involved a great emphasis on making by hand, with the aim of producing objects of use and beauty, and focused on simplicity of design, the textures of ordinary objects and the use of ornamentation for particular purposes. The thinking behind the Arts and Crafts Movement’s ideals was strongly influenced by architectural theorist, art critic and social critic John Ruskin (1819-1900)[8], who explored and expounded in his writings upon the challenges of the era of industrial expansion[9]. For Ruskin, art and architecture were inseparable from the society by which and for which they were produced. He warned against the moral and social pitfalls that he associated with mechanization, and argued for the centrality of ‘truth’ in art. William Morris (1834-1896), furniture and textile designer, artist, writer, poet and socialist, was also extremely important in the genesis of the Art and Crafts Movement. Morris was concerned with similar issues, and as the design historian Gillian Naylor describes, both individuals “believed that beauty was as necessary to man’s survival as food, shelter and a living wage, and that this essential could only be achieved within a society in which all men would work, take pleasure in their labour and share their delight in its results”[10]. In a quotation from another of the Movement’s key figures, the designer Charles Robert Ashbee (1863-1942), the preoccupation with the educational, moral and social value of the crafts is also expressed as an imperative: “The crafts are a protection against waste; they are an educational necessity; they are part of the community’s leisure, and do themselves grow out of leisure; they are, in short, a great human need, and in a mechanistic age they take their place among the humanities…”.

As these quotations suggest, the Arts and Crafts Movement’s focus was not exclusively upon the life of the individual craftsperson in isolation. Rather there was an underlying belief in the necessary interconnectedness of artists and craftspeople (as indeed of all humanity), as well as a belief in ordinary people’s right to have objects of use and beauty. For many proponents of Arts and Crafts ideals, the formation of groups of like-minded people, working together under explicit sets of values and standards, became important. This found expression in different ways. In 1861, for example, the firm of Morris, Marshall, Faulkner and Company, Fine Art Workmen in Painting, Carving and Furniture and the Metals was established. This group of designers, makers and retailers set out in a manifesto its intention to produce objects ranging from stained glass and metal work to furniture, for which decorative art would be designed and applied by the makers themselves. It was the more cooperative concept of the ‘guild’, however, that was taken up and experimented with at Ditchling and elsewhere.

LEFT: Title page from Guide book of Ditchling, 1926, with kind permission of Ditchling Museum. RIGHT: Philip Hagreen, ‘Eat more fruit’ print, with kind permission of Ditchling Museum. Image reproduced courtesy of Philip Hagreen’s family.

Medieval guilds were associations of merchants or artisans, designed partly to maintain standards and partly to protect the interests of guild members. The precise motivation behind the Arts and Crafts guilds varied: for example, the foundation in 1878 of Ruskin’s Guild of St George was perhaps primarily that of social reform rather than craft standards. The guild model continued to be developed and experimented with by the Arts and Craft Movement. The Art-Workers’ Guild, founded in 1884, largely functioned as an association of artists and makers, some of whom were socialists, which enabled and supported intellectual debate. Whilst it had initially been hoped that this group would also make efforts to promulgate examples of Arts and Crafts work to the wider public, this did not transpire. In 1888, therefore, it became the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society (ACES) with an explicit mission to make work more widely known and better understood: organizing exhibitions and communicating the philosophy underlying the work. For Morris, the notion that an annual exhibition was the way to bring about the necessary transformation of values and standards in arts and crafts at first seemed misguided. He gradually became more supportive of the work of the ACES, but was keen to emphasise the scale of the problem as he saw it. There was a need, Morris argued in this preface to an ACES essay collection, to counteract the utilitarian philosophy so dominant in late Victorian Britain. This meant tackling the inability of British society at large to appreciate and understand the importance of artistic beauty:

‘ Those who practice art must nowadays be conscious of that practice; conscious I mean that they are either adding a certain amount of artistic beauty and interest to a piece of goods which would, if produced in the ordinary way, have no beauty or artistic interest, or that they are producing something which has no other reason for existence than its beauty and artistic interest. But having made the admission let us accept the consequences of it, and understand that it is our business as artists, since we desire to produce works of art, to supply the lack of tradition by diligently cultivating in ourselves the sense of beauty (pace the Impressionists), skill of hand, and niceness of observation, without which only a makeshift of art can be got; and also, so far as we can, to call the attention of the public to the fact that there are a few persons who are doing this.’

Preface, Arts and Crafts Essays by Members of the Arts and Crafts Exhibition Society, 1893.

Behind Morris’s plea was a sense that the processes of industrialisation had lead to an over-emphasis on the profit motive, and to a deterioration in the understanding and awareness of aesthetics, particularly in relation to decorative art and craft. Concerns about the effects of industrial working processes and practices were clearly not limited to the Arts and Crafts Movement; considerable attention had also been given to the poor standards of British industrial design by the Government and the Press (see Chapter 1). This had been the impetus behind the establishment of Schools of Art, and it was hoped that through these new institutions, an improvement in the quality of design could be nurtured and British industrial competitiveness sharpened. For the Arts and Crafts Movement, the business of good design was inextricably linked with a morally-informed and holistic approach to work and life. Whilst not simplistically anti-industrialist, the Arts and Crafts Movement developed partly out of the belief that the existing industrial standards and working patterns needed to be radically reformed.

Louis Ginnett and Charles Knight, Stained glass window, with kind permission of Brighton, Hove and Sussex Sixth Form College.

With this concern for principles and harmony in working and family life, the early Arts and Crafts Movement and some of the Arts and Crafts guild experiments were strongly influenced by Utopian notions of living simply in small, self-sustained rural communities, such as C R Ashbee’s community at Chipping Camden, and that at Ditchling. It is worth mentioning at this point, however, that though the use of the term ‘Arts and Crafts Movement’ might imply a homogenous phenomenon, there were many differences in individuals’ views; there were also variations in the value-systems of the various Arts and Crafts communities, and in the way they organised and approached their work.

Creative communities: Ditchling and the Brighton School of Art

Sussex Arts Club members including Charles Knight (middle row, 4th from right) and Louis Ginnett (middle row, 3rd from right), with kind permission of Ditchling Museum.

The character of the Ditchling community was informed by the vision of a simple, rural way of life[11] but also deeply influenced by the strong Catholic faith of the founders Eric Gill and Hilary Pepler. The cornerstones of the community they established were to be adherence to their religious beliefs in all aspects of their life, and the practice of consistently high standards in their artistic and craft activities. Thus the Guild of St Joseph and St Dominic was set up as a working fellowship, the constitution for which begins, ‘The Guild holds: 1. That all work is ordained to God and should be Divine worship’ (see the illustration of the Guild constitution). The Guild itself underwent changes over the course of its history, beginning with strictly Catholic and male-only membership but eventually (after initial serious objections) allowing non-Catholic makers to join, and admitting Jenny KilBride as the first female Guild member in 1974. Whilst it was the Guild that provided the impetus and the focus for the Ditchling arts and crafts community to develop, their way of life and creative endeavours attracted a wider and more diverse group of artists and craftspeople to settle in the village. Thus there are notable figures who did not belong to the Guild of St Joseph and St Dominic, who are yet still very much part of the arts and crafts ethos of Ditchling.

Ditchling had appealed to Gill and many others partly due to its long history, its traditional way of life and the beauty of the countryside; it offered a self-contained and peaceful space in which their ideals could be translated into practice. Brighton had been chosen in the mid-nineteenth century as a location for a School of Art for sharply contrasting reasons: it was viewed as a lively, creative conurbation able to nurture the talent that industry needed. Yet as both the Brighton School of Art and the Ditchling community grew and developed, connections and influences between these very different entities proliferated.

Fine art painting

Louis Ginnett, ‘Portrait of Mary’ c. 1925, with kind permission of Ditchling Museum.

Louis Ginnett (1875-1946) was a painter primarily of portraits and interiors, a mural painter and a designer of stained glass. He exhibited widely in his lifetime, including at the Royal Academy, and was one of the British artists selected to be exhibited by the British Council in 1912 in Venice. He is of particular interest in the context of Brighton and Sussex in a number of respects, having been a member of the Society of Sussex Painters, produced a series of mural panels on the history of Sussex for the hall of Brighton Grammar School[12] and taught for many years at the Brighton School of Art[13].

Although Ginnett lived in Ditchling (in the High Street), he was not a member of the Guild of St Joseph and St Dominic. He was, however, influenced by some of the sources and styles that contributed to the ‘Arts and Crafts’ ethos prevalent in the community.[14] In a letter of thanks thought to have been addressed to Charles Alfred Morris, President of the Society of Sussex Painters, Ginnett commented that ‘an empty picture is what I can’t abide. I suppose my boyhood study of the Pre-Raphaelites is responsible’[15]. His murals and stained glass window designs in the Brighton Grammar School Hall also show an Arts and Crafts awareness of keeping decoration in proportion with utility, as the panels in the Hall were designed specifically to harmonise in scale, shape and subject matter with the room. The paintings for which Ginnett is perhaps best known are the portrait studies of his daughter Mary, in which the use of colour and emphasis on the strong form of the neck and shoulders recollects elements of the Pre-Raphaelites’ work. Ginnett is mentioned as a tutor in the context of several of the other artists connected with the Brighton School of Art and featured in this book, and was a particular influence on Charles Knight.

Knight (1901-1990), another long-standing resident of Ditchling, although not a member of the Guild of St Joseph and St Dominic, was also a significant figure in Brighton School of Art. He won a scholarship to the School in 1919 and left with a Diploma in 1923; as a student he was influenced particularly by Ginnett and by architect John Denman. As D Wootton writes, Brighton School of Art’s ‘conventional focus on figure drawing … complemented his [Knight’s] already developed study of landscape. The syllabus inevitably included anatomy, but also grounded the student in aspects of painting, the fundamentals of modelling, printmaking and textile design, and the history of arts and architecture. These studies would both confirm Knight’s conception of fine art as a craft and assist his working in areas beyond his specialty of painting, such as etching and architectural design.’ His teaching career at Brighton ran from 1926 to 1967, the last 8 years of which were as Acting Vice-Principal and Vice-Principal. Knight was a traditionalist landscape painter whose subjects were taken from Sussex, Devon, Wales, Yorkshire and Scotland. Combined, Ginnett and Knight were influential individuals at the Brighton School of Art and part of the Ditchling community over a period of several decades.

Woven textiles

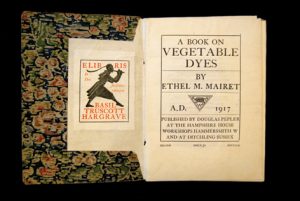

Ethel Mairet, title page to A book on vegetable dyes, 1917, with due dilligence and kind permission of Ditchling Museum

An early addition to the Gill and Pepler’s Ditchling community, Ethel Mairet had already been collecting, studying and writing about textiles for some years when she arrived in 1914. Mairet had initially been particularly drawn to indigenous techniques, colours and patterns following a period of time spent in Ceylon and India, and had then experimented with weaving in the Arts and Crafts community at Broad Camden in the Cotswolds. At Ditchling from 1918-1920, Mairet set up weaving and dyeing workshops known as the ‘Gospels’, and there took on a role in training many students and apprentices. She spent much time exploring the effects that could be created with vegetable dyes, writing a book on the subject published in 1916, and used machine-weaving as well as hand-weaving techniques. Mairet was greatly interested in demonstrating and educating, teaching weaving at the Brighton School of Art[16], exhibiting her work widely, publishing a number of books and articles and producing what she referred to as ‘textile portfolios’ with accompanying pamphlets to support teaching.

Ethel Mairet, Tam-O’-Shanter, with due dilligence and kind permission of Ditchling Museum.

Both Mary Barker and Marianne Straub had close experience of Mairet, with Barker apparently referring to ‘the rigours’ of working with Ethel Mairet[17]. Barker took over from Mairet to teach weaving at the Brighton College of Art in 1950. Barker herself had specialized in weaving in Leeds, and took the opportunity in her visits to the Gospels to experiment with creating a range of stoles and scarves in silk, wool and cotton. Barker also exhibited widely, including with the Brighton Phoenix Group from the 1950s until 1982. Straub, the daughter of a Swiss textile merchant, had received her education in weaving in Zurich and then Bradford. She, too, spent time at the Gospels in order to learn more about hand-loom techniques, although she also remained interested in the question of creating and sustaining high standards in industrial weaving processes. She received the Royal Designer for Industry in 1972. Straub, who was a visiting lecturer at Brighton College of Art, was a widely respected textiles teacher.

Silversmithing

Dunstan Pruden, Rosary, on long term loan to Ditchling Museum, with kind permission of Anton Pruden of Pruden & Smith.

From 1934, Dunstan Pruden was a head of Silversmithing at Brighton College of Art. As described in the extract from Pruden’s autobiography (see Chapter 3) the interest he felt and the pleasure he took from teaching was constrained by the desire to have time separate from College life to concentrate on practising his craft; a tension experienced by several of the teacher-practitioners of Ditchling. Pruden developed a method of working directly in silver that demanded a particularly high level of skill and a substantial amount of time on the part of the individual silversmith. The conception, planning and crafting of individual pieces was of great importance to Pruden, stongly influenced as he was by Arts and Crafts Movement ideas. In his teaching he had an impact on Michael Murray, Anthony Elson and Gerald Benney, the latter being the son of Ernest Sallis Benney who headed Brighton College of Art in a period of development and expansion in the 1930s.

Gerald Benney, Silverware, University of Brighton Design Archives.

Benney trained under Dunstan Pruden, working closely with him in the silversmithing workshops at Brighton College of Art and at Pruden’s own workshop in Ditchling for one day a week. Like Pruden, Gerald Benney was a highly creative designer keen on strong and simple designs, and a technical innovator, creating a ‘bark finish’ which his work became known for. However Benney was also interested in mass market work as well as handcrafted specialist pieces, producing for example successful designs for Viners cutlery manufacturers. Benney became a Royal Designer for Industry (1971). As can be seen above, the arts and crafts community of Ditchling was not simplistically opposed to industrial processes: in some cases individuals were open to the possibilities that design standards might be raised in industry, and that it was useful and important for a craftsperson to have knowledge of industrial processes. For others, skilled hand crafting was intrinsically more worthwhile: Pruden, for example, had ‘thought it a pity’[18] that Benney had become so involved in industrial design.

Wood-engraving

In 1916, shortly after Gill and Pepler arrived in Ditchling, Pepler founded St Dominic’s Press. The purpose of the press was not only to enable the production of hand printed books but also to retain and develop fast-disappearing specialist printing skills and to provide a vehicle for the skills of the community’s artists and crafts people. Gill himself, artist and poet David Jones (1895-1974) and then Philip Hagreen contributed images. Hagreen, who joined the St Joseph and St Dominic Guild in 1923, was a wood engraver with a distinctive lettering style who also taught at Brighton College of Art. Hagreen developed a style of engraving designed to instruct and educate and deliberately drew on much older elements of engraving design to give an archaic look to his work. Hagreen was also one of the individuals who founded the Society of Wood Engravers in 1920. The Society held an exhibition annually featuring work by, among others, Clare Leighton and David Jones. Hagree was also a Distributist[19]. In parallel with his religious and political work, Hagreen produced many posters and bookplates with humorous and secular designs.

Pottery

Bernard Leach, a major figure in British twentieth century pottery, taught as a Visiting Lecturer at Brighton College of Art just before the Second World War. Leach trained initially as a potter in Japan, developing his skills over several decades, and was fascinated by oriental forms and by Eastern philosophy. Leach had a strong belief in the significance of making by hand and was influenced by William Morris’s ideas, believing that ‘the nature of work affected the person who made it and should be a “joy to the maker and to the user” ‘[20]. He tended to use minimal decoration and a muted palette on strong forms. In 1920, Leach established his influential pottery studio in St Ives and took on a number of apprentices who went on to become successful art potters in their own right. These included Katherine Pleydell-Bouverie and Norah Braden, who worked together at Coleshill pottery. Braden also taught at Brighton College of Art.

A continuing tradition of arts and crafts inspiration, education and practice

Today, in the Faculty of Arts and Architecture’s home in Grand Parade, Brighton, it is well worth looking up on entering the bulding’s foyer to see the physical reminders of the longstanding interconnections with Ditchling. The decorative terracotta panels mounted on the northern wall of the foyer were designed by Alexander Fisher, headmaster of the Brighton School of Art from 1871 to about 1892, and produced by Messers Johnson of Ditchling.[21] Originally made for the first dedicated School of Art building, they were saved and displayed when the College was rebuilt in the 1960s. They are now often to be seen in juxtaposition with displays of recent or contemporary works.

John Vernon Lord, illustration from The Nonsense Verse of Edward Lear, 1979, pen and ink. The Aldrich Collection.

Whilst the Guild of St Joseph and St Dominic was closed in 1989, the arts and crafts tradition at Ditchling continues in other ways, as does the link with the now Faculty of Arts and Architecture at the University of Brighton. Ditchling Museum, developed through the efforts of, among others, Hilary Bourne (herself a practitioner and pupil of Mairet), performed an extremely important role in conserving, analysing and communicating the legacy of the Ditchling arts and crafts community. Located in the heart of the village, it has built up archives of objects, documents, books and ephemera and provides a valuable resource for both visitors and researchers. The Museum offers an accessible and evocative insight into type of craftsmanship and way of life the Ditchling Arts and Crafts community developed, at the same time as supporting research and scholarship, including the current links to the University of Brighton, which might lead to fresh perspectives. The Museum also supports contemporary practitioners exploring processes and materials through exhibitions and access to the collection.

Importantly, the tradition of artists and craftspeople choosing to live in the village and surrounding area has also continued. These include illustrators John Vernon Lord, Professor of Illustration at Brighton (who taught at Brighton from 1961-1999 through three institutional manifestations), and Raymond Briggs, author of books including The Snowman, Father Christmas and When the Wind Blows. The silversmith Anton Pruden, grandson of Dunstan, and Rebecca Smith, continue to run their business from the centre of Ditchling village. All added importantly to the research for the anniversary book, and to the pool of images with which it has been illustrated.

Chapter text, Philippa Lyon

[1] The east window of the south porch of St Margaret’s Church, Ditchling, was designed in 1947 by resident artist and Brighton School of Art tutor, Charles Knight.

[2] The Museum has both a permanent collection relating to Ditchling’s arts and crafts heritage and a social history archive about the village.

[3] Pruden & Smith in South Street, Ditchling, is jointly directed by Rebecca Smith and Anton Pruden; the latter being the grandson of Dunstan Pruden, see Chapter 3.

[4] Fiona McCarthy, for example, responds to criticisms of Gill’s morality by arguing for the separation of life and work in her article, ‘Written in Stone’, The Guardian, Saturday 22 July 2006.

[5] This was the view that emerged from research interviews carried out by the authors, such as with Marc Hoar, architecture student from 1959-1965 and architecture lecturer for approximately 30 years, and Mary Hoar, Brighton College of Art administrator in the 1960s (jointly interviewed on 18 September 2008).

[6] Referred to in the account of Knight’s time at Brighton (p11), by David Wootton, in the introductory essay to …more than a touch of poetry: landscapes by Charles Knight 1901-1990(London, Chris Beetles Ltd.: 1997).

[7] Gill, together with the printer, writer and poet Hilary Pepler, arrived at Ditchling in 1907, converted to Catholicism in the same year and founded the Guild of St Joseph and St Dominic in 1921. The Guild was formally closed in 1989.

[8] Although it should be noted that scholars have placed the origins of the Movement further back. Naylor, for example, argues that the precursor of the Arts and Crafts ideas was architect and designer Augustus Pugin (1812-1852).

[9] Ruskin’s The Stones of Venice, the first volume of which was published in 1851, contained ideas that were taken up as particularly important to the Arts and Crafts Movement.

[10] p27, The Arts and Crafts Movement: a study of its sources, ideals and influence on design theory (London, Studio Vista: 1971).

[11] A concept explored in detail in Fiona MacCarthy’s The Simple Life: C R Ashbee in the Cotswolds (1981).

[12] This is now Brighton and Hove Sixth Form College (BHASVIC), where both panels and stained glass remain today.

[13] Photographer and painter Thurston Hopkins recalled Louis Ginnett’s presence at Brighton School of Art in the 1930s and said ‘we were aware of Ditchling. Very much.’ (Interview with the authors, 31st July 2008).

[14] Ginnett may have been influenced by the presence of Frank Brangwyn (1867-1956), artist and muralist and a key figure to the Ditchling artistic community.

[15] Undated letter from Ginnett to Charles Alfred Morris, Documents collection, Ditchling Museum.

[16] The Ditchling weaver Valentine KilBride also taught at Brighton School of Art according to his daughter, the weaver Jenny KilBride.

[17] This reported description of working with Mairet features in an article on Mary Barker by Enid Russ, Journal for Weavers, Spinners and Dyers, 190 June 1999, p11.

[18] See Chapter 3, Art College Life in the 1930s.

[19] Distributism was a Catholic political philosophy based on the idea that ownership of the means of production should be spread as widely as possible among the population, rather than held by a central authority such as the state. G K Chesterton was one of its main proponents.

[20] Entry by Emmanuel Cooper on Bernard Howell Leach in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

[21]Eric Gill’s alphabet, carved in stone, in also in the Grand Parade foyer.

March 15, 2024 at 3:34 pm

Hello there,

When Clare Leighton (1899-1989) was a student at Brighton Art College in about 1917, the Leighton family lived in Keymer, a village about eight miles inland from Brighton.

I live in Keymer and enjoy very much the evocative woodcuts depicting rural life made by Clare Leighton.

I have been trying to find out the location of the house in Keymer where the Leighton family lived during this period, using Kelly’s Directories, but I have had no luck.

Would Brighton Art College, in its archive of alumni, contain the address of Clare Leighton when she was a student at the College?

I would be most obliged if you could supply me with this information, if you still have it.

Best regards, Graham McGee