Chapter text, John Vernon Lord

First impressions of the art college in 1961

When I came to Brighton as a part-time lecturer I was twenty two years old, with hardly any professional work behind me. Nor did I have any qualifications to teach. Dapper John Biggs, the Head of Graphic Design (with a white goatee beard and bow tie) somehow had faith in me as a teacher of drawing and illustration. He interviewed me for a long time, peering over his specs at my portfolio of work.

On my first day at the art college, in November 1961, I taught a group of six first year National Diploma in Design (NDD) Illustration students. I got them to sketch around the busy market in Circus Street next to the college. The sun always shone on Wednesdays and during that first year I took students sketching round the Royal Pavilion, furniture auctions, the two piers, Pavilion Gardens, the art college garden (then a romantic wilderness with a small pond), the beach, the Lanes, Black Rock, the race course, Rottingdean’s pond, the Aquarium, Brighton Museum, Stanmer Park, the ten-pin bowling alley, the station, various streets and markets, churches, Queen’s Park and the allotments. Teaching was spent in ideal circumstances. I spent nearly all my time with the students and I didn’t have to attend any meetings during my first four years! My job was to get the students’ sketchbooks ‘up to scratch’, as John Biggs put it. Drawing from direction observation was the key activity.

A part-time lecturer’s salary was eight guineas for a five hour day. There didn’t appear to be such things as formally agreed syllabuses (other than producing the required sheets for the Intermediate or NDD examinations) and students were taught by different part-time lecturers on each day of the week. As teachers we rarely met each other during the course of an academic session and consequently the students carried out different projects on each day of the week.

Most of the teaching staff were part-timers and most of us travelled by train from London. The regular journeys we made up and down the line helped us to get to know each other. We tried to catch the Brighton Belle train at 5.25 pm to get back home. This was a non-stop Pullman train with spick and span buffet carriages that took an hour to get to Victoria. It was nearly always on time. We had to pay a surcharge of two shillings to travel on these exclusive trains, which had steward service and tables clad in white tablecloths with lamps. The stewards wore white jackets with bow ties. Here, we would relax with a drink and a good conversation after a day’s teaching. The Brighton Belle service was withdrawn in 1972.

Mike Rouillard, 1968/69 poster for Alexander Nevsky, dir. Sergei Eisenstein and Dmitry Vasilev (1938). With kind permission of Mike Rouillard. The poster was made for the art college film society, which screened classic films such as La Strada by Fellini (1954), Repulsion Polanski (1965), The Battleship Potemkin (1925), Freaks (1932), Hunchback of Notre Dame, The Golem, Cabinet of Dr Caligari and many more.

The illustration teachers, when I began at Brighton, were Gaynor Chapman, Molly Richardson, C Walter Hodges and John Lawrence. We were joined not long afterwards by Raymond Briggs and Justin Todd. Leslie Cole (a former war artist) and Peter Cresswell (who later became dean at Goldsmith’s) taught drawing. The main graphic design lecturers at the time included Harold Cohen, Don Warner, Frederick C Herrick [p 00] and Miriam Goluchoy. Frank Eddison and Dermot Goulding taught photography. Colleagues who were to join us later in the 1960s were Jim Bartholomew, Clive Chizlett, Paul Clark, Tony Cobb, George Collett, Maggie Gordon, Tony Halliwell, Leon Roberts and Geoff Trenaman.

When I came to teach at Brighton Dick Cowern had been the art college principal since 1958 and Charles Knight was the vice principal, as well as the head of fine art. In the old building, the principal’s office was situated near the area where the Sallis Benney projection booth on the mezzanine floor of the current Grand Parade building now is. Outside his office there was a display of staff work. The other heads at this time were John Biggs (graphic design), Ronald Horton (education studies), Frank Green (architecture), and Mary Bryant (fashion textiles).

Registers were taken of student attendance each day and these were collected from the main office. Most of the students received grant awards from their county education authority and their fees were also paid. If students’ attendance was poor their authority could get to hear about it, which might stop their maintenance grant.

In the bustling art college office you would encounter the pipe-smoking Tod Saunders, the registrar who, with the principal’s secretary Frida Oldfield, was in charge of the administration of the college. Mr Jack Brown, replete in dark uniform, was the authoritative head caretaker, who walked around the college like a policeman. His deputy was Frank Homer, later to be joined by a youthful Mike Wise.

In the art college days, full-time academic staff were permitted to practice and research, not only a day per week during term time but throughout most of the vacation periods. This also applied to the principal, vice-principal and heads of department. The college was like a morgue during the mid-summer period. The administration of the college was left in the capable hands of the principal’s secretary, the registrar, the head janitor, and the secretaries and clerks. By the time the mid 1970s arrived everything changed in this respect. Much of the interviewing of students who were applying for courses started to take place in the Easter vacation period. By this time all full-time staff were expected to be available during the first and last fortnights of the summer vacation. This took a lot of getting used to for those who had taught in the old art college days.

The art college buildings

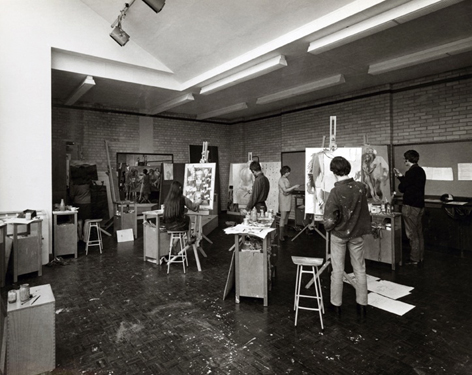

During the first years I taught in the two ground floor studios of the old School of Science and Art building that fronted Grand Parade. The lithography workshop was situated just behind the right hand studio as you faced the building. When this building was being demolished, a number of unscrupulous people took away the huge casts of Classical figures that used to grace the corridors and the large north-facing life-drawing studios. Fortunately the two terracotta lunettes in bas-relief, which were inset into the outside walls of the building, were just rescued in time before further thieving hands managed to get hold of them. These have now been mounted in the foyer of the Grand Parade building. In those days, when you entered the old building, it had a typical art college whiff of turpentine, oil paint and printing ink.

There was a tiny crowded library, which Leslie Wilmot used to run in the old art college building before accommodation was made available in the new north wing of the Grand Parade building. It was where you would bump into the genial Robert Logan, a polymath who lectured upon all manner of subjects.Leslie inherited a higgledy-piggledy arrangement of shelves upon which were crammed a small selection of well-thumbed dusty volumes. It was a place to sneeze in. In the early years of the 1960s it was Leslie, with the backing of his newly appointed staff, who initially made a huge contribution in transforming the situation and creating the beginnings of a first class modern library for the college.

The stage one new east wing building that fronts William Street had just been completed. It was built at a cost £140,000 and was completed in March 1962. This mainly housed the printing courses, painting and decorating, furniture-making, modelling and sculpture workshops, and the future foundation course. A large gymnasium at that time was reserved for the art history lectures, which was later to be used by the three dimensional design and expressive arts courses.

Dorothy Coke, ‘The Demolition of the old College of Art, Brighton’, 1963-6, pencil, biro and watercolour. From the Aldrich Collection.

The original art college building was demolished in 1964/5 with most of the graphic design work being carried out in annexed Regency buildings on Grand Parade, which used to stand north of the Glenside Hotel. Printmaking and architecture were temporarily housed in the Circus Street annex. The art education department, the painting, and life-drawing studios were all placed in the crumbling old St John’s School annex, which used to stand where the present staff car park now stands.

Previous to that the art education department had been housed in the old church hall that stood next to the old art college building, where the Sallis Benney Theatre is now situated. The hall ran alongside what was then Carlton Hill (now Kingswood Street). This was where lectures took place and where the art college parties were held. The demolition of the old college and the church hall was graphically portrayed in the wonderful set of sketches by Dorothy Coke, who had taught at Brighton from 1939.

These old buildings gave way to the stage two buildings. These were formally opened by Sir Thomas Monnington, President of the Royal Academy of Arts. The ceremony took placeon 1 June 1967 in the new hall, which eventually became the Sallis Benney Hall, named after a former principal. Other accommodation included the refectory, the library and studios. Graphic design used two studios. The stage two buildings were built at a cost of £268,000, with an entrance on Grand Parade. It contained a lecture hall, fine art and graphic design studios, a library, refectory and kitchens.

Front and north corner of the Percy Billington Grand Parade Art School building.

The art college annexes sandwiched between the old building and the Glenside Hotel (roughly where the south gallery on Grand Parade is now situated), were in a constant state of disrepair. Wallpaper hung from the ceilings and the handles to the doors were such that they took you through a history of doorknobs and handles over the past hundred years. A mighty thunderstorm, with a torrential cloudburst, fell on the first day of June in 1964. I had never seen rain like it. The roads became streams and the cars looked like boats encircling Grand Parade. Just as teaching had begun there were panic noises from the upper storeys of the annex building where I was teaching, owing to the collapsing of the ceiling that had flooded with rainwater. The fourth floor leaked water on to the third, and then it came through to the second and first floors and eventually found itself dripping down the light fitting on to the ground floor. Even during my last year in 1999 (working on the top floor of 78, Grand Parade) a foul smelling water poured through the ceiling after heavy rainfall, owing to the accumulation of seagulls’ droppings and nests that had been built on the roof over the years.

For many years in the 1960s I taught drawing with Leslie Colein the old St John’s Primary School up the hill, now a car park. The old school also housed the education department and a number of fine art studios. We had drawing classes in a room with a partition that divided it into two. In the winter months we were kept warm by the glow of two flaming coal fires and two gas fires. Shovels and pokers were often in action to keep the fires going. During the last day of term before ChristmasLeslie and I would throw a party for the students in our drawing class. Leslie brought several bottles of his homemade wine, made from beetroot and gooseberries. We roasted dozens of chestnuts and baked several pounds of potatoes beneath the grates of these fires, anointing them with butter and cheese. These parties lasted from ten o’clock in the morning till five in the afternoon. Having been a primary school previously, naturally catering for the size of young children, the pegs for our coats were fixed very low down on the wall and it was very difficult to squeeze into the tiny lavatories (originally designed for children) and close the doors.

The third stage of the art college building, the one that continues along Grand Parade, was completed by the time the new academic session started in September 1969. It was built at a cost of approximately £170,000. This building included the exhibition gallery, administrative offices, the board room, studios and the photography unit. Three well-equipped studios accommodated each of the three years of the Diploma in Art and Design (Dip AD) course in Graphic Design. They were planned to each take a maximum of twenty-four students. We had a new typographic workshop and a graphic design lecture theatre. The vocational graphic design course occupied a studio upstairs, where the printmaking and etching studio is now. We heard at the time that there were future plans to develop a final sealing-off ‘fourth’ wing and this partly came into fruition in 1998. The Department of Education Studies (art) had recently moved to 2, Sussex Square from the old St John’s school, and the latter was converted for use by the Department of Architecture and Interior Design.

The surroundings close to the art college

The Casbah, at 76, Grand Parade, was where quite a number of the art college staff used to dine in the early 1960s. A lunch here (comprising chicken noodle soup, steak and mushroom pie with vegetables, bread and butter pudding and a cup of coffee) cost four shillings and nine pence. This is now occupied by the Royal Hotel.

Dennis Creffield, ‘Still Life’, c. 1961, oil on board. From the Aldrich Collection. Taught at first by David Bomberg, Creffield went to the Slade 1957-61, was a major prizewinner and exhibited widely. In 1961 he was a prizewinner in the John Moores Prize Exhibition, Liverpool, and in 1977 he won a major Arts Council of Great Britain Award for Painting. From 1964-68 he was Gregory Fellow in Painting at the University of Leeds. ‘Still Life’ was shown in Made at the Slade, mature works by ex-Slade students, Brighton Polytechnic Gallery, 1979. He was a Senior Lecturer in Fine Art at Brighton, 1968-81. In 1987 Creffield was commissioned by the Arts Council of Great Britain to draw all twenty-six medieval cathedrals which were exhibited at the Albemarle Gallery in 1991, and are now owned by the Tate Gallery, London.

I had the occasional bed and breakfast in the down-at-heel Glenside Hotel before it was purchased (with its labyrinthine corridors and tiny rooms) for the art college some time in the early 1960s. Glenside became an important annexe, until it was finally demolished to make room for the new fourth wing in the 1990s.

The Norfolk Arms, at 51/52 Grand Parade opposite the northwest corner of the art college, (now called Hector’s House) was the main art college pub for many years, which became crowded on the last days of term. It was run by the taciturn Ken and the lively Audrey. We used to have chess competitions here involving staff and students. These were the days when pubs were not inundated with loud piped music.

Gwatkin and Son the chemist at 49, Grand Parade (next to what was then Champions the pram shop) advised students on medical issues without them needing to see a doctor. When the Gwatkins finally retired in the 1980s the students threw a party and presented them with flowers and a gift, thanking them for all their help over the years. They were absolutely astonished, having not realised that the students held them in such high regard.

Standens, the newsagent at 74 Grand Parade, supplied us with newspapers, magazines, tobacco goods, small snacks and soft drinks for many years. This shop closed down in 1998 and is currently occupied by Pendragon Pictures, an art gallery and picture framing service.

The basement in one of the Grand Parade annexes was the Students’ Union area in which there were offices and a bar, famous for its bar and the Friday Night Club.

Other departments and disciplines

The art college was relatively small in the 1960s and there was plenty of opportunity to mix with staff from all departments both academically and socially. Among architecture colleagues, I would bump into

LEFT: Jennifer Dickson, ‘Le Silence’, 1965, coloured etching, artists proof. The Aldrich Collection. RIGHT: ‘Professor John Vernon Lord’, Kenny McKendry, 1999, oil on board. The Aldrich Collection.

Stephen Adutt, Michael Blee, Geoffrey Bowles, and John Lomax. In printing I would encounter John Evans, Reg Appleton, Roy Boothby, Morris Dixon, Les Heath and the long-serving George Knight, and in bookbinding, John Plummer and David Igglesden. Fashion textiles colleagues, whom I recall meeting, were Mary Bryant and Mary Barker. Colleagues inpainting and decoratingincluded Douglas Fray and Peter Fisherand infurniture, Ernest Joyce. The potters at this time were Charles Bone and Trentham de Leliva, later to be joined by Sean Hetterley. In art teacher education I knew Ronald Horton and Gerald Leet. Bevil Roberts,Luther Roberts and Paula Pike were to pioneer the structure of the new foundation course, and it was Geoffrey Holden, who, with Bevil, was to develop the wood, metal, ceramics and plastics degree course. Oscar Thompsett taught the ‘adult education’ classes for many years. Violet Igglesden and Pat Elliott were appointed secretaries in the mid 1960s and both continued to support courses for over 35 years.

The fine art tutors in the early 1960s included Norman Clark, George Hooper and John Lake (Curator of the Towner Art Gallery in Eastbourne, 1947-58). Ian Potts, a recent student from the Royal Academy Schools, began teaching at this time. New fine art staff, who came to teach a little later, were Patrick Burke (who headed painting for some years), and other colleagues, Dennis Creffield, Cyril Reason, Roy Grayson and the sculptor Philip Hartas. Part-time staff at this time included Brian Crouch, David Whittaker, Michael Browett, John Hilliard, John Bellany. Gwyther Irwin was appointed Head of Fine Art in 1969, following James Tower’s resignation, a position Gwyther was to hold for fifteen years.

Printmaking

I taught lithography for a short while. These were the days of drawing on stone, and if you were lucky, on zinc plates. This involved a lot of repeat teaching, going through the process of lithography several times with many students

during the early weeks of the autumn term. It was important in those days to advise the NDD students how best to employ their use of colours and using thin printing inks so that they could take advantage of the extra colours that arose out of overprints, particularly when often using just three stones or plates. We didn’t have offset presses in the early 1960s and most of the work was done on stone.

The lithography workshop was in a mess until Harvey Daniels was appointed full-time to look after it. Everything suddenly became tidy and clean once Harvey had arrived on the scene, with all the bottles neatly labelled and returned to their rightful place upon the shelves. Harvey wore exceptionally smart clothes when he was helping students print in the lithography classes. On one occasion I saw him rolling up a student’s print in the workshop: he was wearing an orange and mauve chequered shirt with large starched cuffs and enormous cuff links at the wrists, an impeccable pinstriped suit with a carnation pinned to the lapel and shiny pointed shoes. With such immaculate attire he would not only roll up students’ prints but also get involved in applying asphaltum, turpentine, and gum Arabic. Games of ‘Shove ha’penny’ were a feature of the lithography workshops later on when they were removed to the ground floor of Circus Street and for a short while there was a craze for playing table tennis. Harvey’s clothes were a feature during table tennis matches. He would wear eye-teasing polka dot shirts that resembled the Op Art works of a Vasarely, so that you could hardly see the ping-pong ball when it moved across his body.

Jennifer Dixon was in charge of printmaking in the 1960s. Printmaking was scattered on various sites. Jennifersupervised the etching workshops, which were housed in rooms in Circus Street. Peter Hawes was soon to join Jennifer as an academic colleague in etching. Molly Richardson was the main member of staff in graphic design looking after the lithography area and I taught lithography to fine art and graphic design students for a short while. In the early days Harvey had the assistance of the ever-helpful Bert Latham. Selma Nankivell was in charge of the silkscreen area, which was eventually given accommodation in the Glenside. Tony Bachelor and Sue Gollifer became her youthful technicians. Brian Rice was appointed as part time teacher of printmaking during this era. Laurence Preece was a student when I first taught at Brighton and eventually he was to return as a tutor in printmaking and ultimately the course leader of the MA Printing and Fine Art course.

Photography

Photography was still a relatively new subject at the time and, like printmaking (except for etching), it was managed by the Graphic Design Department. It was taught in the early 1960s by the enlightened photographer Dermot Goulding, who had established sound practices in the subject before he moved on to St Martin’s School of Art in London in 1964. Tom Buckeridge was to succeed him. Tom had previously taught at Leicester College of Art and had worked extensively as a professional photographer. When Tom first came to Brighton, students used to have to wait until the heavy vehicles on Grand Parade had passed by before they could print their photographs, such was the shaking of the old annex building. It was Tom who designed and planned the photography studios and dark rooms that still exist in Grand Parade today. He used to drink very strong-smelling homemade soups, the aroma of which would linger in his office for the rest of the day. As soon as he’d finished lunch he would sprint towards the nearest antique shops and often get involved in bidding at auctions, particularly when it came to oriental rugs and jelly moulds. Inside his greenhouse at home, he had citrus trees and one of his huge lemons, grown in 1978, held the record weight for a lemon grown in the United Kingdom. The lemon weighed in at a mighty 3 pounds and 9 ounces (1.628 kilograms). I had the pleasure of announcing it at a board of studies at the time. This can be seen on the cover of the 1978 edition of the Guinness Book of Records showing his daughter Thomasine holding it. At the same time as Tom’s appointment in 1964, Bill Whittaker and ‘Phil’ Philippe were appointed as technicians in the photography section.

Cross discipline activities

‘Peep behind the scenes at Brighton’s dynamic art college’, Brighton School of Art Archive, The Design Archives.

In the mid 1960s there wasn’t a strict demarcation of subject disciplines. Many staff taught across courses and students from different courses got to know each other through meeting during the art and design history and complementary studies seminars. There were often criticism sessions (known as ‘crits’) and discussion groups for cross-discipline projects, to which staff and students in all departments would contribute. I recall a large mural crit, which involved staff and students from architecture, fine art, graphic design and art history.

John Boulton Smith and Frances Walker were both very good at galvanising students in cross-discipline cultural activities. In 1965 I recall attending several events in the Sallis Benney Hall. One was an absorbing symposium organised by John Boulton Smith centred on the creative world of the 1890s. This was presented by students from all departments. Another event was a production by the graphic design student Ron Ford of a Ionesco play The New Tenant, performed by graphic design students, in which Ollie Williams was the tenant. Paddy Fletcher wrote and produced a play by Anouilh. In April 1967 students and staff from all departments got together to put on an evening’s entertainment entitled ‘Hogarth’s England’ as a Brighton Festival Fringe event. This was devised by John Boulton Smith and Rod Harman. In May 1969 the studentsput onan excellent symposium about Villon’s life, with another script by Paddy Fletcher. For its time this was a most bawdy performance with suggestive and descriptive mimes. Liz Kneen directed Oliver Williams and Siân Morris in a fine production of Pinter’s The Applicant and Adrian Swales directed a group in Shaw’s The Shewing-up of Blanco Posnet.

Art history

Before the advent of the Dip AD there were hardly any staff teaching art history and complementary studies. Robert Logan was one, and he mostly taught the fine art students. John Biggs taught the history of design and professional practice. Now that these studies were to be put on a more formal basis for the new Dip AD courses, a new Department of Art and Complementary Studies was set up and headed by Jean Creedy, a former schoolteacher. She brought together a distinguished group of colleagues to teach in the department in the 1960s. John Boulton Smith (an Edvard Munch specialist), Kathleen Morand (medieval painting and illumination), Karl Huter (medieval painting) Ray Watkinson (William Morris and the pre-Raphaelites, Bewick and Hogarth), Ian Jeffery (illustration and photography), Ralph Berry (English literature).George Simunek (architecture), and Gillian Naylor (history of design, who later taught at Kingston and later became the Professor of Design History at the Royal College of Art).

Art history and complementary studies were to give rise to some impassioned discussion among staff and students in the art colleges in the ensuing years. These studies became a focus of considerable controversy during the period of student unrest in 1968.

Student unrest during the summer term of 1968

By the summer of 1968 the Dip AD courses had been running for nearly five years. During this time there was very little formal academic organisation and structure at Brighton or any other art college. Everything tended to be conducted in a somewhat ad hoc manner and there was very little continuity. Most of the teaching was carried out by means of one-to-one tutorials. The academic staff would mostly ‘do the rounds’ of the studio and discuss each student’s work on an individual basis. Most of the staff were part-timers who came in to teach on one or two days a week. Now and again there would be briefing sessions, demonstrations, lectures and crits, when the students would be gathered together.

By the summer of 1968 the Dip AD courses had been running for nearly five years. During this time there was very little formal academic organisation and structure at Brighton or any other art college. Everything tended to be conducted in a somewhat ad hoc manner and there was very little continuity. Most of the teaching was carried out by means of one-to-one tutorials. The academic staff would mostly ‘do the rounds’ of the studio and discuss each student’s work on an individual basis. Most of the staff were part-timers who came in to teach on one or two days a week. Now and again there would be briefing sessions, demonstrations, lectures and crits, when the students would be gathered together.

Students had little formal opportunity to give voice to their concerns about courses or air their views generally, and were not represented on any committees. There were some heads who thought that students had nothing to contribute. There was trouble brewing among the students regarding the art history/complementary studies element of the courses. There was a view that the 20 per cent element of the course was wagging the tail of the 80 per cent ‘chief’ or ‘main studies’ (the names given to practical work at the time, as opposed to theoretical). Some believed that theory and practice should be integrated more, rather than seen as separate entities. Many sought a more flexible use of the workshops.

At Brighton the teaching of art history/complementary studies took up a whole day of the week and the students had a heavy workload of essays that could hardly be accomplished within the timetabled period of that one day. In other words they were being overloaded and in many cases their practical work was being neglected as a consequence of this. There was no flexibility in the timetable either. The one day a week was sacrosanct and to be taught only on days that suited the Art History and Complementary Studies Department. This caused resentment among the students and many of the staff who were teaching main studies.

Heads ran their departments without course committees and they held the purse strings without much transparency. ‘Accountability’ was a word rarely used at the time.

The spark of student discontent began in France. There were street riots, sit-ins and occupations in the universities there, most noticeably in the Sorbonne in Paris. Students were protesting about their poor working conditions and a need for educational reform. They were disaffected because they had little influence on the governance of the institutions. In the UK a similar disaffection flared up in Hornsey College of Art (now part of Middlesex University) and Guildford School of Art and it spread to other art colleges, including Brighton. A significant number of staff in all these colleges supported the students in their quest for seeking formal opportunities to air their views. Better communication and more transparency in the running of courses were issues high on the agenda alongside student representation in the colleges’ committee structure. Students were also seeking ways of crossing strict departmental boundaries, wanting more flexible opportunities to work across subject disciplines. Depth and breadth were other issues that preoccupied them.

The period of student unrest had been a grim one to experience. It had created a climate of confusion and tension among all those concerned and it had brought about divided loyalties and had caused a breakdown in mutual trust in some quarters. The summer vacation period of 1968 and the events of spring 1969 had left many staff and students utterly exhausted.

The unrest was something that was waiting to happen, not necessarily in the way it did but in terms of the main issues that needed to be aired and resolved. With hindsight the events of the summer term brought Brighton into a greater state of maturity and responsibility. As Bob Strand put it: ‘When during the course of 1968 and 1969 the heat of the eruption subsided, the way was open for a more formal, more clearly defined but more democratic and participatory community to be established in each college.’ [1]

The last years of the art college and the shift to polytechnic status in 1970

In 1968 we were settling down into our new premises in the new Grand Parade wing. We had a new canteen for students on the top floor with a small dining room for staff leading from it. David Whittaker, one of the fine art staff had organised a group of students to make a large mural on the ceiling representing a map of the British Isles and featuring the counties. Mr Singer was the refectory manager and in those early days of what turned out to be a short-lived staff dining room. For a brief while it was like having a sophisticated restaurant on our doorstep. We also had a vast Senior Common Room (with serving hatch and lift) where we could meet for morning coffee. The new fine art and first year graphic design studios, the sleek new library (with brand new shelves), and the large new hall, with its extraordinary curvilinear diorama, changed the whole atmosphere of the art college. Everything suddenly became streamlined in appearance in what was then a state-of-the-art, custom-made building. Gone was the old fashioned and lovable art college. Everything suddenly looked new, but it was not yet clear whether course management and institutional organisation had also moved with the times.

Ian Potts, ‘Sunlight in the marble quarries, Carra, Italy’, 1978, pen and wash. The Aldrich Collection.

May 1966 had seen the publication of the Department of Education and Science’s A Plan for Polytechnics and Other Colleges; Higher Education in the Further Education System. This concerned the development and expansion of higher education within the further education system, involving a review of the existing provision ‘in order to build up a strong and distinctive sector of higher education which is complementary to the universities and college of education’. The Secretary of State, in consultation with the regional advisory councils, intended to designate a limited number of polytechnics. As far as Brighton was concerned the College of Technology and the College of Art were included in the list of likely colleges to become a polytechnic.

The notion of creating polytechnics brought about a great flurry among many art colleges, which feared their loss of autonomy. Concerns were expressed by the NCDAD, principals of art colleges, including Dick Cowern, and prominent artists. Initially the art college teaching and technical staff at Brighton were tentative about the new arrangements that might arise out of becoming a polytechnic. Many thought that the new institution would impose unhelpful educational procedures that might be alien to the way we taught art and design. There was a dread that ‘they’ would not understand our approach to teaching and practice. In those days most of us called our research work ‘practice’. In the 1960s the art college mainly comprised part-time academic staff who were practising professionals in their field of activity. The College of Technology mainly consisted of full-time staff. We wondered, at the time, how we would be able to share what we suspected could be entirely different approaches to educating students. We suspected that it might be difficult for our technological colleagues to come to terms with what we artists and designers did. The creation and making of images and objects seemed to be worlds apart from the nature of work carried out by our new colleagues in the College of Technology.

LEFT: Brighton Polytechnic Faculty of Art and Design Calendar 72/73. Brighton School of Art Archive, The Design Archives. RIGHT: Brighton Polytechnic Faculty of Art and Design Calendar 1973/74. Brighton School of Art Archive, The Design Archives.

In August 1969 we finally heard from the Department of Education and Science that the formation of Brighton Polytechnic would take place, from the merger of Brighton’s College of Art and College of Technology. The merger was to be completed for a start in April 1970.

Meetings began to increase considerably from 1968 onwards and committees and working parties bred like rabbits. It seemed as if a boil had burst after the summer of student unrest. Discussions were often tense. The distinctive articulacy of student representatives on committees surprised those who didn’t think students would be able to make any useful contribution. It is interesting to consider that not only were students having more responsible involvement in committees in the art colleges, but also that the age of majority was lowered from 21 to 18 years in Britain by the beginning of 1970.

These issues were entirely different from those who thought that the merging of the two institutions would bring about a complete loss of identity for the two colleges. Some thought that power and control would be lost for each of the institutions when they were merged into a single entity. It is significant that an outside appointment was made when the new director Geoffrey Hall, from Imperial College London, was chosen to lead the polytechnic.

The late 1960s had been a very tough period for Dick Cowern, and the student unrest had taken a great deal out of him. When he suffered a short period of illness, Alan Roberts, the vice-principal, took charge of the college. Soon afterwards we were to become part of the Polytechnic. Alan left Brighton to become Vice-Principal of the London College of Printing, and Jean Creedy left too, to become the Principal of Hastings College of Art.

In March 1970, Dick presented his last principal’s report to the art college governors, covering two sessions. [2] The art college student numbers at this time were 643 full-time, 715 part-time day, and 344 part-time evening. His report referred to the period of his review as being ‘an eventful and fruitful one; first in forging the means of full academic consultation, then in their use, successfully revising course structures and syllabuses through months of elaborate and exhaustive discussions’. He also mentioned that Student Union representatives were ‘now members of the Academic Board, Boards of Study and several Sub-Committees’ and two student members had also attended meetings of the Board of governors as observers. The nearest reference he makes to the period of unrest is perhaps this passage: ‘There has been full consultation between staff and students in all Departments of the College and at Academic Board level and any difficulties that have arisen have been solved. I feel that now the general relationship between students and staff is good’.

Dick Cowern also mentioned in his final principal’s report the ‘crippling cuts’ that had brought about very serious deficiencies. He was particularly concerned about the problems of accommodation in the School of Architecture and Interior Design for which ‘quite drastic expansion… may be vital for survival,’ he wrote. He expressed his gratitude to the various chairs and the past and present governors who had supported the college over the years. It was through their support, he wrote, ‘that the college has achieved its present outstanding facilities and status. We now enter the Polytechnic with confidence and zest.’

[1] Robert Strand, A good deal of freedom, CNAA, 1987. Bob Strand was appointed Registrar of Art and Design for the CNAA in 1974 following the amalgamation of the NCDAD and the CNAA. He had been Deputy Chief Officer to the NCDAD and a former Principal of Epsom School of Art, His book gives a very clear account of ‘Art and Design in the public sector of higher education, 1960-1982’.

[2] This was entitled Principal’s Review Session 1968-69 and Autumn and Spring Terms 1969-70, Brighton College of Art,

September 3, 2024 at 4:52 pm

I attended Graphic Design classes 1956-59 at Brighton Art College. (I emigrated to Canada 1959) A good friend Ted Owen was in the Silversmithing Courses and I would like to know if he did pursue this career as Pruden taught at that time…

August 9, 2025 at 9:37 am

Ah!

Brighton Art College.

I was there 1971 -5.

Graphics.

I graphicced and acted with Frances Walker for the festival.

Somewhat underestimated (easily done),

I was advised that working somewhere like Hull might give me opportunity for work!

Within 2 weeks of leaving I was working a Hull missed out on my talents.

Witgin 9 months I was,working for the BBC and commuting.

My meagre talents continued to find employment for all of my career, although the fun of Brighton college could never be repeated.

Thanks to all who remember.

Keith Worthington