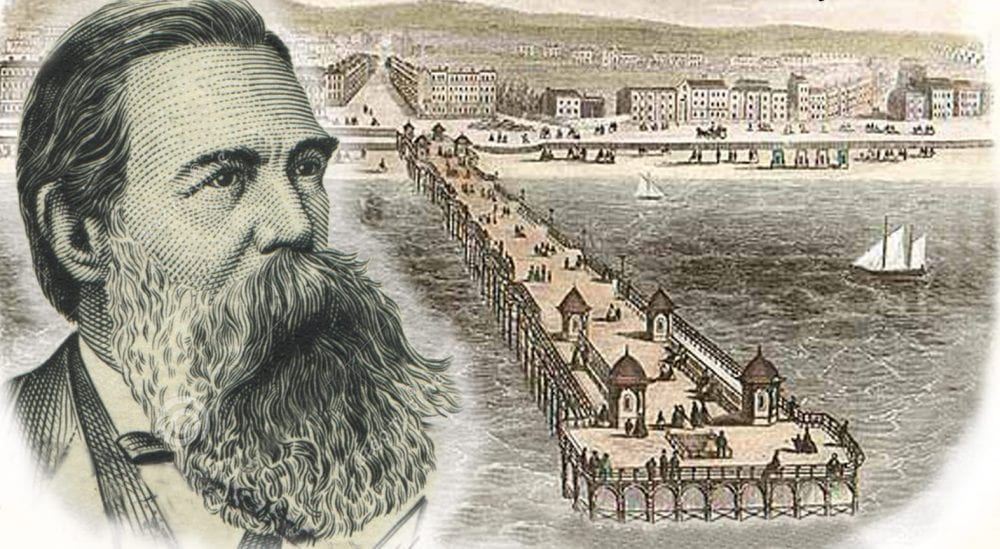

28 November 2020 marked the bicentenary of the birth of Friedrich Engels, the German radical philosopher who in works such as The Condition of the Working Class in England (1845), The Peasant War in Germany (1850), The Housing Question (1872), ‘The Part Played by Labour in the Transition from Ape to Man’ (1876), Anti-Dühring (1877), Socialism: Utopian and Scientific (1880), Dialectics of Nature (1883) and The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State (1884) made pathbreaking and profound contributions to modern social and political theory. As the co-thinker of Karl Marx and co-author of The Communist Manifesto and ‘The German Ideology’, he played a critical role in the forging and development of classical Marxism specifically. But like Marx, Engels was ‘above all a revolutionary’, who also played a role in revolutionary upheavals such as the German Revolution of 1848 and in the international socialist movement.

When Engels died in London on 5 August 1895, at the age of 74, his last wish was that following his cremation his ashes be scattered off Beachy Head, near Eastbourne. Marx and Engels had visited many Victorian seaside resorts, such as Margate, Ramsgate and the Isle of Wight, but Eastbourne was Engels’s favourite place and where he holidayed for extended periods during the summers in later life.

As Tristram Hunt notes in his biography of Engels,

Friedrich Engels had begun his remarkable life in the furnace of Germany’s Industrial Revolution, amongst the yarn bleacheries and textile works of the Wupper valley; he concluded it amidst the Victorian elegance of the Duke of Devonshire’s fastidiously English seaside retreat, Eastbourne. By the 1880s this gentlemanly resort had become his favoured holidaying spot, where he liked to take a well-positioned house along Cavendish Place hosting Nim [Helene ‘Lenchen’ Demuth], [Carl] Schorlemmer, Pumps [Mary Ellen Rocher] and her brood – as well as Laura [Lafargue] or Tussy [Eleanor Marx] if he was lucky. There Engels sat, the lover of the good things and happy times in life, with Pumps’s children crawling around his knees, an open bottle of Pilsener, a letter on the go and a stoical resolve in the face of the August mist and rain.’ (Tristram Hunt, The Frock-Coated Communist, Penguin, 2010, p. 350).

On July 1881, a few months before his wife Jenny’s death on 2 December 1881, Karl Marx and his wife Jenny both stayed at 43 Terminus Road (now part of the site of Edinburgh Woollen Mill shop). Engels wrote to Sorge on 18 March 1893 that he had spent two weeks in Eastbourne and ‘had splendid weather’, coming back ‘very refreshed’. Engels would also stay at Regency Villa, Marine Parade. ‘Tomorrow, Louise (divorced wife of Karl Kautsky, the famous German Social-Democrat) and I are going for a week to Eastbourne (address as before, 28 Marine Parade) as I need to regain a little strength before my journey to Germany….. ‘ (Letter to Lafargue, Marx’s son-in-law, 20 July 1893). Engels often stayed at Astor House, 4 Cavendish Place ‘near to the promenade and opposite the pier’ (Letter to Laura Lafargue, second daughter of Marx, dated 19 August 1883). He wrote his last letter from this address to Laura date 23 July 1895. After his death on 5 August 1895, on 27 August 1895 in a very stormy sea Eleanor Marx (youngest daughter of Marx), Edward Aveling, Eduard Bernstein and Frederick Lessner in a boat took the urn containing his ashes and dropped all into the sea two miles off Beachy Head. As Lessner notes, ‘Engels’s will stipulated that he was to be cremated, and his ashes thrown into the sea. This last wish was fulfilled on August 27th, when Eleanor Marx, Dr. Aveling, Herr E. Bernstein, and myself, travelled to Eastbourne, hired a boat, and two miles from the coast threw his ashes into the sea.’

As Eduard Bernstein (who estimates that they went five or six miles out, rather than the more realistic two miles suggested by Lessner) later recalled,

To the west of Eastbourne the cliffs along the coast gradually rise until they form the great chalky headland of Beachy Head, nearly six hundred feet in height. Overgrown with grass on the top, it slopes gently at first, and then suddenly falls steeply to the water, while down below it exhibits all manner of recesses and outlying masses. From the landward side an extremely fine drive leads up to the summit. Enterprising visitors have repeatedly attempted to climb Beachy Head from the beach at low tide, whereby many have nearly lost their lives. If they were unable to reach the top, and the tide rose in the meantime, they were left between the devil and the deep sea. From the coastguard station, which stands at the highest point of the Head, it is impossible to see what is happening on the face of the cliff, nor will a call for help carry thither. Only if he is noticed from the direction of the sea can the climber count upon help.

About five or six miles off Beachy Head, in the year 1895, the Avelings, the old Communist Leaguer Friedrich Lessner, and myself, on a very rough day of autumn, cast into the sea the urn containing the ashes of our Friedrich Engels. Engels … had directed, in a letter enclosed with his will, that his body should be cremated and the ashes thrown into the sea. And since we knew of his predilection for delightful Eastbourne, the sea off Beachy Head was chosen as the most suitable spot for the execution of this portion of his last will and testament…

Beachy Head and the Lighthouse in 1906

For more on the detail of Engels’s life in Eastbourne, see the 1975 article ‘Engels in Eastbourne’ by Hymie Fagan from Visual History, 1 (1975) – reproduced on this website here with the kind permission of Terry McCarthy.

For more on the (continuing) efforts in Eastbourne to commemorate Engels in the town after his death please see here