When we speak of Digital Cities, there is a tendency to imagine a futuristic Blade Runner-esque environment where cars hover at the height of skyscrapers and humans and cyborgs eat together at stalls in slums that sell cheap artificial food. It seems a very distant future, if not actually fictional, but throughout this module we come to understand that we are actually already there.

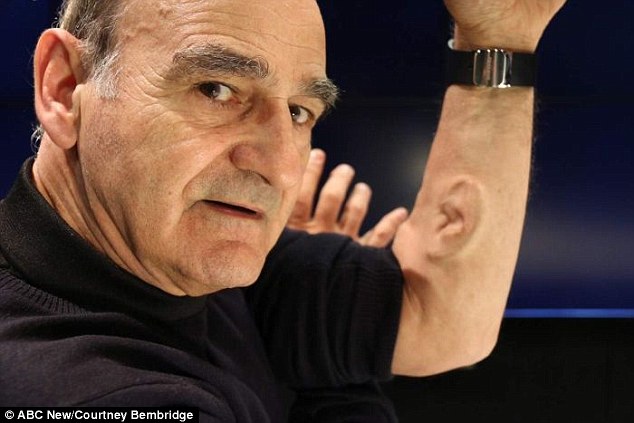

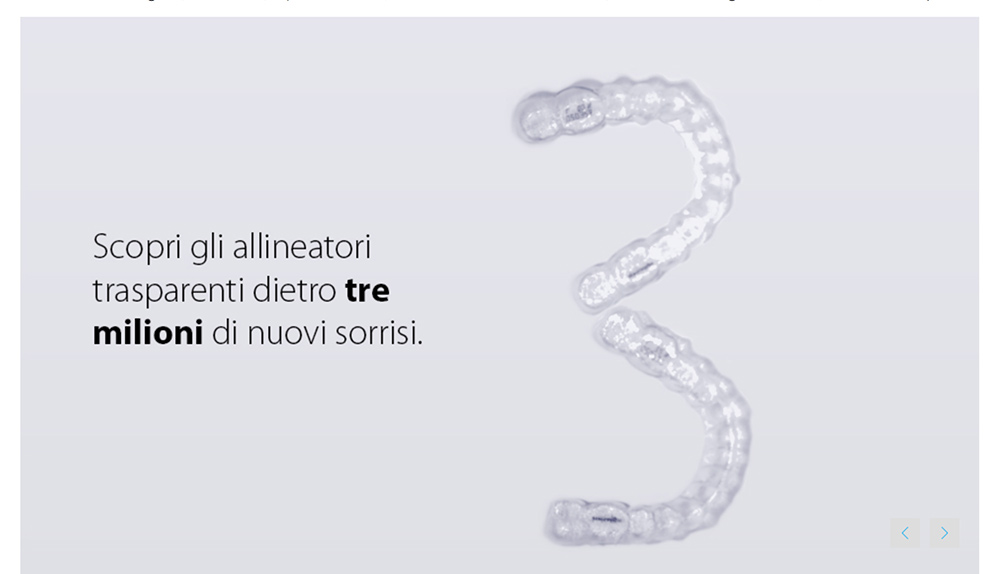

With the advent of 3D printing, it is becoming increasingly possible to construct new body parts that mesh naturally with ours (Formosa, 2016), so the cyborg reality is not that far away. Both Volkswagen and Toyota have been working on prototypes for hover cars since 2012, and the existence of an all-seeing Orwellian entity in our society has already long been accepted – except that we are our own Big Brother, telling everyone everything all the time, whether through Facebook statuses or GPS data (Ferguson, 2016).

But the concept of Digital Cities is not just about a grim dystopian high-tech future where we no longer control our own lives.

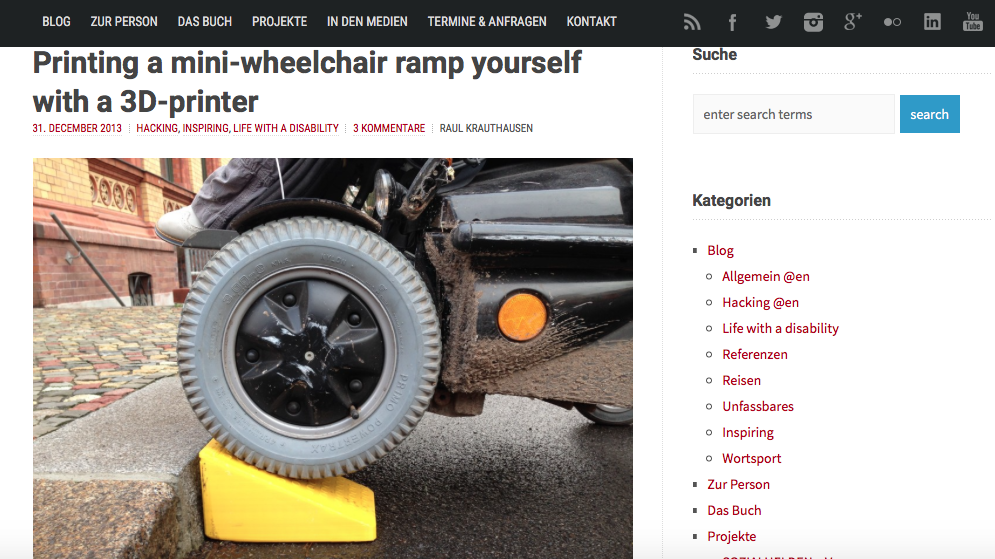

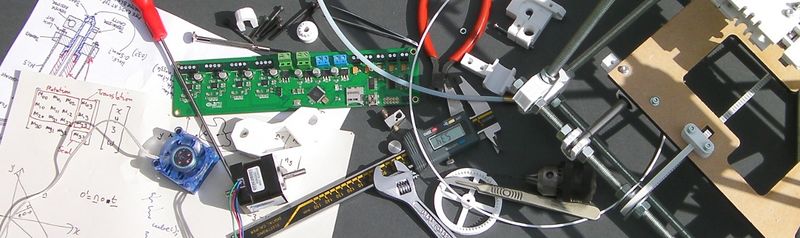

It is about taking back the control of the technology that runs our lives and use it to improve the world around us – whether that is through apps that allow us to monitor air quality or 3D printing our own wheelchair ramps without having to wait for the intervention of governing bodies (Jones, 2016)

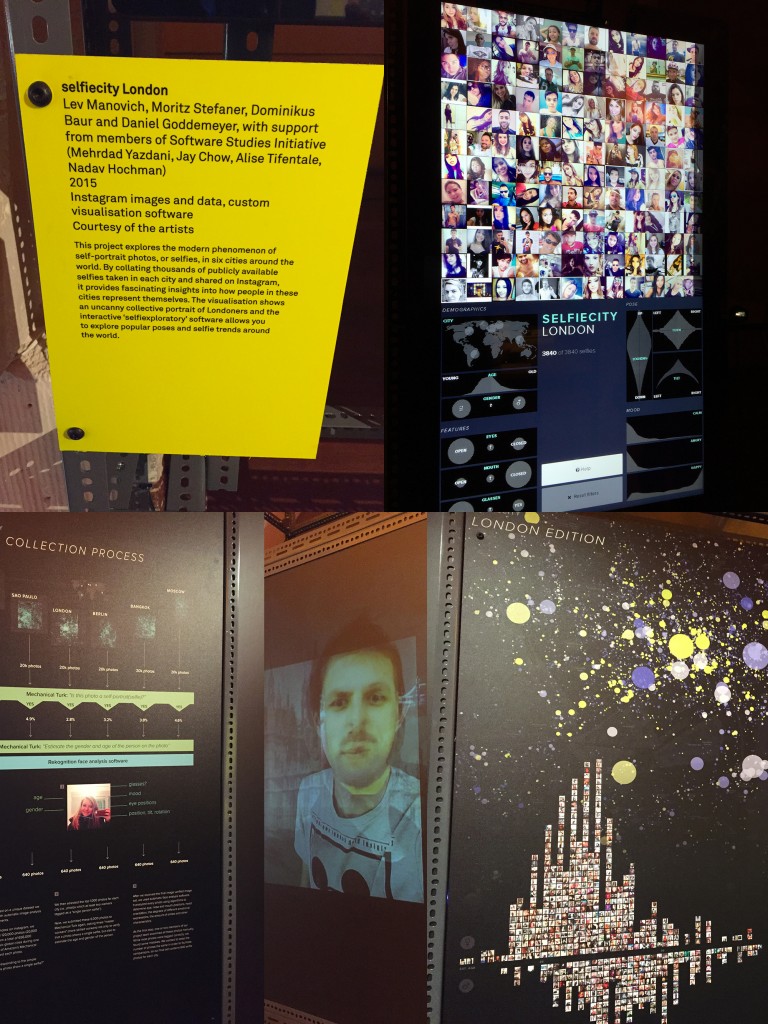

It is about becoming increasingly aware of how we interact with mass media and how much information we complain is being ‘stolen’ is actually being spoon-fed by us to massive companies like Google and Facebook through the guise of social media and fun apps – such as Foursquare and Instagram.

The digital lives that we lead are not necessarily bad, but these is still such a fascination when it comes to the ubiquitousness and ease of use of technology that we are increasingly less aware of our actions and their consequences not only as individuals, but as citizens, both digital and not. ‘Texting and driving’ was not a problem in 1970, and I’m quite sure Ballard or Huxley never mentioned the concept.

The technological possibilities are there for our cities to become increasingly digital in a way that leads us into a better future, but it’s on us now, and how we use those technologies to our advantage. If we want our Digital Cities to be a utopian and not a dystopian reality, we need to realise that the ball is in our court now. The technology we need is everywhere and it is becoming increasingly easier to use. We just need to take a moment, think, and start using it consciously instead of taking another selfie or blindly checking in at our local kebab place.

—

Ferguson, Juliet, Even Your Cat Can’t Hide, 28 February 2016. < https://blogs.brighton.ac.uk/digitalcities/2016/02/28/even-your-cat-cant-hide/ >

Jones, Janet, Ramp It Up!, 8 May 2016. < https://blogs.brighton.ac.uk/digitalcities/2016/05/08/ramp-it-up/ >

Formosa, Adolf, Bits to Atoms and Atoms to Bits, 10 May 2016. < https://blogs.brighton.ac.uk/digitalcities/2016/05/10/bits-to-atoms-and-atoms-to-bits/ >

Pena, Ines, From Grassroots to the Atmosphere, 3 May 2016. < https://blogs.brighton.ac.uk/digitalcities/2016/05/03/from-grassroots-to-the-atmosphere/ >