Items of interest

As I mentioned before, the documentation process allowed me to make note and plan for any more challenging issues that myself and Melissa Williams might come across during conservation and I thought I would share a few of those with you.

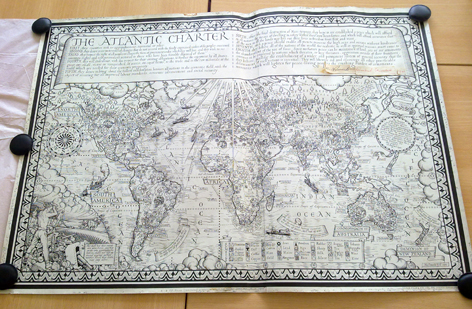

The first piece I’ll talk you through is the Atlantic Charter map from 1942. This item is a pen and ink original and has a variety of very interesting issues to bring up. The dimensions of the charter are 1100 x 775 mm and it has been constructed from two separate large pieces of paper stuck together. On the image above you can just see the slight bend on the surface where the two pieces are joined together. This off-middle joint consequently has a thicker feel to it compared to the rest of the paper.

Under the main banner of text there are three pieces of ink of paper attached – the date 1941 and two signatures. On the left is a signature of Franklin Roosevelt and on the right an original signature of Winston Churchill. All of these pieces have been adhered to the original artwork with what, at first inspection, appears to be an animal-based glue. These types of glues have the tendency to become very brittle and yellow in colour with age. The hardened residues of glues like this can be removed by scraping with care. These three additional pieces will need to be secured during conservation.

There is also an additional piece added to the original artwork at the bottom edge of the item. This appears to state the producer of the poster and will also need to be secured properly. The problem with these adhesives on any piece of art is that it they leave a permanent stain that does not really respond to washing treatments. The best that can be done is scraping away any residual adhesive and securing any such pieces to the original by using a wheat starch paste. This paste is used widely in paper conservation. It is easily reversible as it is soluble in water and it doesn’t leave any unwanted stains on the paper.

As I had mentioned before, this particular piece is a great example of showing something that isn’t intended to be in a ‘final piece’ and could, by some, considered to be unwanted markings. But as, after all, this is an original piece of artwork; Gill’s ink markings along the edges are beautiful little pieces of evidence of a work in progress.

Another piece that I thought I would use as an example is the draft watercolour from 1946 map designed to go aboard the Queen Mary ship. This item has the dimensions of 1600 x 806 mm. Before this piece was rolled up, it had been folded, as the fold creases run all across the object from left to right. It is not only an original draft watercolour, but also has ink handwriting in the top right corner area and below it, two photographs adhered to the paper.

The whole object is made up of segments of paper – there is one larger piece where the watercolour painting is that has been joined together with four smaller pieces of paper.

For whole objects that have been built up in this manner, any decision about aqueous treatments would need to be even more carefully considered than usual. When paper comes in contact with water, the fibres within it expand. If an artwork is made up of several sections and is not taken apart before washing, these sections can become separated. Once the pieces are separate, and wet, they would need to be left to dry before attaching them back together again. When paper dries, it contracts and if pieces are washed separately, or come apart during washing processes, the chances are that they will not fit together again as well as they did before wetting. The way in which paper acts and reacts has also to do with its grain direction and if joined pieces have grain direction running in separate directions, the piecing together will become even more difficult.

For the Gill material, there is a general understanding that no aqueous washing methods will be used in the conservation of these materials due to time and budgetary restrictions. However, some materials might need to be humidified before flattening if the heat press will be deemed unsuitable.