Salvage and Emergency Planning

Last week I had the fantastic opportunity to travel to Birmingham to attend a 3-day course/workshop organised by Historic England, in collaboration with the West Midlands Fire Service. The course was titled ‘Salvage and Emergency Planning’ and was made up of practical and desktop exercises, as well as lectures, on all things salvage from museums, historic houses and archives in case of a fire or flood. The course was taught by Charlie Harris (Fire Safety Adviser for Historic England), Beth Stanley (Senior Collections Conservator), Christine Murray (Preventive Conservation Adviser for the National Trust), Fiona Macalister (Independent Conservator) and Nick Hunt, Mark Ralston and Clive Williams (all from West Midlands Fire & Rescue Service).

The course was centred around the importance of developing a good relationship between a museum, archive or historic house and their regional Fire & Rescue Service in preparation for an emergency event taking place. This relationship should involve working with the Fire & Rescues Services to, in effect, make them aware of the salvage and emergency plans in place with a collection. Obviously great focus was also given to salvage procedures and the treatment of water damaged items in particular.

We started out with the fire side of things with Nick, Mark and Clive all giving us valuable ‘inside’ information about the way in which the Fire & Rescue Services operate. For example, different members of the team can be identified by their helmets. The hierarchy goes from Fire Fighter, Chief Commander, Watch Commander to Station Commander. We also had discussions and practices on more general (and often forgotten) health and safety procedures. I thought this was an excellent aspect of the course, as when an incident happens in an archive/museum/historic house situation, it is important for the salvage teams to have clarity on who they need to speak to and liaise with. Fire & Rescue Services’ first call is to save lives, but they will help with the salvage of historic and archival materials.

One of the most valuable and eye-opening exercise was to experience first-hand what fire fighters face when they enter any building. The house in which we did all our practical exercises had been set up as a historic house with various pieces of furniture, books, paintings, crockery and archival materials. We entered the practice house in groups, in the pitch black, with smoke (‘club smoke’ in this instance!) surrounding the place. We went up and down stairs with zero visibility to attempt to find the fire, which ended up being located on the top floor of the 3-storey training house. It was incredibly disorientating, confusing and scary – even in a practice situation. I had massive respect for the Fire & Rescue Services before, but this has increased tenfold after this ‘hands on’ experience.

And yes, we were kitted up with the gear…. Who says conservators don’t get to wear uniforms?

In our fire training instance, one person was unaccounted for, so saving a life became the priority for the Fire & Rescue Services. Thankfully, they were rescued unharmed… if a little floppy.

The other main aspect was going through and practising various flood, burst pipe and other water-related -scenarios – getting rather soaked in the process! The water exercises were an absolutely priceless training experience – using tarpaulins, various pipes and a massive selection of other materials to channel water away from the object(s) at risk. For example, working in teams to resolve the best way forward in a running-water-gushing-onto-your-priceless-historic-bookshelf -situation was very rewarding, but also very challenging. The panic sets in, and did so even in a training environment! The practice run also highlighted the importance of one person taking the lead, but while doing so involving all other members of the team in decision making and problem solving. Physically practicing emergency and salvage scenarios also can not be stressed enough!

Having the knowledge of the Fire & Rescue Services’ staff structures is helpful, but what is glaringly obvious is that the staff in an archive/museum/historic house needs to have their emergency staff stuctures clearly allocated if the worse was to happen. These usually include, in hierarchical order from ‘top’ to ‘bottom’: Incident Coordinator, Communications and Welfare Officer, Documentation and Inventory Officer, Quartermaster, Salvage Teams Coordinator, Recovery Teams Coordinator and Salvage Teams (wet and dry). These teams can usually also include Observers, who tend to be external people or people outside of the immediate work unit. Obviously with a smaller team this can become problematic, so this means engaging and training other colleagues and/or ‘external’ people in the specific salvage program and plan.

Every member of a salvage team should know – and practice, then practice again – the role they are responsible for in an emergency situation. However these roles can, and will, be fairly fluid. As you can imagine, it is very easy to panic, so team work and looking after your team members’ welfare, while not forgetting your own, becomes incredibly important. Its is essential to have clear plans on priority items (aka ‘grab plan’). This information should be printed and laminated, so it can also be passed on to the Fire & Rescue service on site. When items begin to come out of the secured premises at which the fire or flood has taken place, clear labelling on where they have come from, documentation on the Incident Coordinator’s exchanges of information with the Fire & Rescue Services and who enters and leaves the building and at what time are very important. We were told the Fire & Rescues Services, once a relationship has been created, are more than happy to be instructed on the correct handling of items too, so this should not be shied away from.

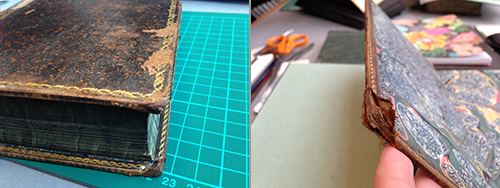

The response to a situation includes the emergency conservation and preservation procedures. The Salvage Teams, with direction from the Salvage Team Coordinator, lead on the wet and dry recovery of items, separating these as they come out. When items have become wet, the importance of being able to start to ‘deal with them’ quickly can not be stressed enough, as mould can very rapidly become an issue. We practiced hands-on techniques and were given tips and guidelines on how to deal with wet items varying from photography and books to taxidermy.

Wind tunnels were created for books to dry by using tarpaulins, plastic crates and fans, while other items such as rugs and cushions were left to air-dry.

There are so many things I learned on this course, but this blog post will have to end somewhere! I can’t recommend the course enough for anyone who works in an archive/museum/historic house: it is an incredibly eye-opening and very educational experience on so many levels. I am pretty sure my colleagues and friends now roll their eyes a little everytime I start a sentence with ‘when I was on the salvage course….’

PS In terms of fire prevention – test out whether your extension lead can handle all the equipment plugged into it with the socket overload calculator provided by Electrical Safety First online. Go ahead, give it a go! It can get a little terrifying though.