CDH Visiting Researcher 2019-20, Miya Itabashi (Hosei University, Japan), reports on research conducted during her time with the Centre in Brighton.

The Representation of Japan at the Brighton Museum and Local Collectors in the Early 20th Century

Miya Itabashi (Hosei University, Japan)

From April 2019 to March 2020, I was given a sabbatical year by my institution, Hosei University, Tokyo, and was fortunate enough to have the opportunity to do research as a visiting researcher at the Centre for Design History, University of Brighton. Thanks to the helpful staff at the CDH, I was able to gain useful support and feedback on my research while there. I would like to express my deepest appreciation for the help offered by the staff at the CDH. My research was mainly focused on Japonisme in book illustrations in late 19th and early 20th-century Britain. This was a new topic of research for me, but I had been eager to explore it in the last couple of years. While I was in the UK, I focused on gathering as many materials as possible in the libraries, archives and museums in Brighton and London. (In hindsight, it was my last chance to do this in the coming few years, as it is now extremely difficult for me to travel to the UK during the pandemic!) While I am now sorting out these treasured materials I gathered in the UK and am preparing to publish articles on this topic, I would like to introduce in this blog another topic I happened to find in Brighton: namely, the representation of Japan at the Brighton Museum and local collectors in the early 20th century, as I think this topic might be of some interest to the people of Brighton in particular.

As many of you might remember, the Brighton Museum & Art Gallery held an exhibition of ukiyo-e prints, Floating Worlds: Japanese Woodcuts, in the autumn and winter of 2019. [1.] I enjoyed visiting this exhibition, and, thanks to the help of Professor Jeremy Aynsley, I had the opportunity to talk with the curator of the exhibition, Fiona Story. After my meeting with her, she kindly showed me the catalogue of the exhibition of Japanese art held in the museum in 1918. [2.] This catalogue includes detailed descriptions of the Japanese exhibits and the names of their collectors. According to the catalogue, the total number of the items displayed was 411. While there were some scrolls and folding screens which were categorised as ‘paintings’ in the western sense of the term, the majority of the items were so-called ‘crafts’ and ‘prints.’ Laurence Binyon (1869–1943), the leading authority on Japanese art in early 20th-century Britain, mentioned in his introduction to the catalogue that the distinction between ‘painting’ and ‘craft’ was less clear in Japan than in the West and that the merger of these categories gave Japanese art unique charm. This was a discourse that was repeated again and again from the mid-19th century. The catalogue describes that the exhibits were lent by or had already been donated by fourteen collectors and indicates the name of the (former) owner of each object. As I did research on these collectors, Fiona Story, Dr. Alexandra Loske and Lucy Faithful at the Royal Pavilion and Museums, Brighton & Hove, kindly offered me useful information and advice during these difficult times. I sincerely appreciate their help. I will pick up and introduce some from these collectors below in order to show the ripples of Japonisme which reached Brighton in the early 20th century after the ‘great wave’ of Japonisme surged in London in the second half of the 19th century.

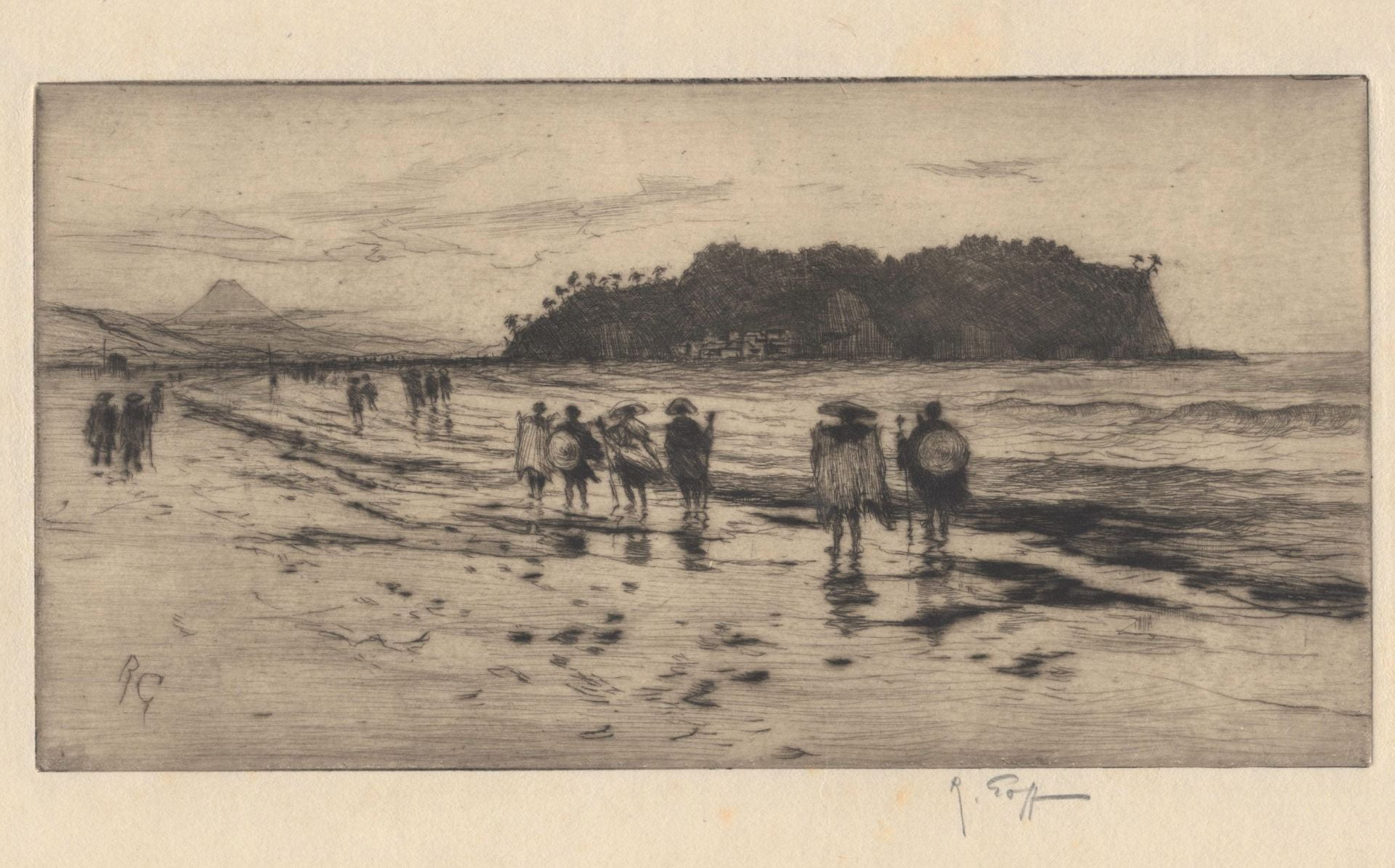

Among the 411 exhibits, as many as 144 were chosen from the collection of one artist, one Robert Charles Goff (1837–1922). Born in Ireland, Goff joined the British army and travelled around the world, including Japan, until he retired as an honorary Colonel in 1878. After his retirement, he devoted the rest of his life to being a painter and an etcher. He also continued travelling around Europe and North Africa but was especially attached to Sussex. He kept his house and studio in Hove for 33 years, [3.] which explains why he lent his collection to the Brighton Museum. Ceramics occupied the largest part of the exhibits from the Goff collection, amounting to 69 items, and covered a variety of periods and areas of Japan. It is not clear if he collected these objects during his stay in Japan as a soldier, but it may not have been very difficult to collect Japanese ceramics after he returned to Britain, as Japonisme was then at its height in Europe. As an artist, he drew and etched some landscapes of Japan, especially the seaside towns in Kanagawa (the prefecture to the south of Tokyo). Among these works, the one I found particularly interesting was an etching entitled Yenoshima, Japan (c. 1910) [image above]. It depicts travellers with Enoshima in the background. Enoshima is a small island connected to the seashore with a bridge and is now a popular weekend destination in Shonan (the seaside area of Kanagawa) for people from Tokyo. It is said that Oiso, the nearby Shonan town, was modelled on Brighton when it was developed as a seaside resort. [4.] It is intriguing to wonder if Goff saw some similarities between Enoshima and the Brighton pier, and between Shonan and Sussex. It has been argued that the British writers who wrote on Japan in the 19th century often depicted Seto Inland Sea (the calm inland sea between the main island and Shikoku island in Japan that has a relatively dry climate) as a parallel to the ancient Mediterranean Sea. In other words, they created illusionistic views on Japan, the remotest area from Britain, and on the era of ancient Greece, the remotest time from the present, in order to escape the dismal realities of their modern world. [5.] If Goff, who actually landed in Japan in the ‘Far East’, saw the familiar English Channel in the seascape of Shonan, that would give another dimension to the argument for the Greco-Japanese illusions in Victorian Britain.

William Giuseppi Gulland (1842–1906) was a well-known merchant in Singapore, and was appointed chairman of Paterson, Simons & Co. as well as a legislative council member of the government of Singapore. He was passionate about Chinese ceramics; his large collection was donated to the Victoria and Albert Museum before and after his death. [6.] He showed his deep knowledge of Chinese ceramics in his book, Chinese Porcelain, [7.] which was dedicated to Augustus Wollaston Franks (1826–1897), the leading figure in the development of the collections of Chinese and Japanese ceramics at the British Museum. After he retired from business and politics in Asia, Gulland seems to have spent the rest of his life at a seaside house in Brighton. [8.] Although he was best known as a collector of Chinese ceramics, he also collected Japanese ceramics and donated his Japanese collection to the Brighton Museum around 1902. It is also recorded that, when donating the Japanese ceramics, he had his collection catalogued by Tanosuke, the Japanese art dealer who will be featured later in this blog. [9.] Gulland was probably not as familiar with Japanese ceramics as with Chinese ceramics, which was why he called Tanosuke from London. For the 1918 exhibition in Brighton, 18 Japanese ceramics were chosen from the Gulland collection, including 11 Imari wares. The reason why Imari wares occupied the largest part of the Gulland collection might have been because of their strong connections with Chinese ceramics. Imari wares were the first porcelains to be produced in Japan and were modelled on Chinese porcelains. Their quality was largely enhanced by the ceramicists who fled from China during the transition from the Ming Dynasty to the Qing Dynasty. Exports of Imari wares to Europe increased dramatically while that of Chinese ceramics declined due to the turbulence during the transition between those dynasties. After the turbulence was settled, the so-called Chinese Imari wares were produced in China and modelled on the Imari wares which had already gained popularity in Europe. Another possible reason for the relatively large number of Imari wares among the Gulland collection was that, in 19th-century Singapore, it might have still been easy to find Imari wares that had been transported by the Dutch East India Company, the only European company that was allowed to trade with Japan during Japan’s seclusion policy, to the Dutch-ruled Malay Peninsula after the 1640s, when the export of Imari wares largely increased. In any case, it is interesting to wonder about the transcultural nature of Imari wares and how the long journey of these items, which had once been popular in the vogue of Chinoiserie in Europe, ended in Brighton in the late 19th or early 20th century in the vogue of Japonisme.

Henry Willett (1823–1905) may need no introduction for readers of this blog in Brighton. As the room of the Willet Collection of popular pottery at the Brighton Museum & Art Gallery shows, Willet donated a major collection of British pottery to the museum. His collection attracted the attention of Augustus Wollaston Franks, the above-mentioned authority on ceramics of various cultures, who encouraged Willet to donate his collection to the British Museum. Franks was one of the people to whom the first catalogue of the Willet collection of pottery, compiled in 1879, was dedicated. [10.] According to the catalogue of the 1918 exhibition, two Japanese ceramics were chosen from the Willet collection, which implies that he collected some Japanese ceramics, though in a small number, along with British ceramics. For the 1918 exhibition, 11 Japanese metalworks, including flower vases and incense burners, were also chosen to be displayed. It is possible to presume that Franks advised Willet to collect these Japanese objects, as Franks was a well-known collector of Japanese ceramics and metalworks. It is also possible to think that the above-mentioned Gulland was advised by Franks on Japanese ceramics. If this was the case, that would show the magnitude of influence of Franks on the collectors of ceramics in the late 19th century.

Leonard Lionel Bloomfiled (c.1858–1916) was a collector of antiquarian books and donated more than 13,000 books and prints to the Brighton Library in 1917. [11.] His collection is known for precious illuminated manuscripts and incunabula. As one of the themes of his collection was ‘costumes’, the Bloomfiled collection included Theatrum Mulierum (1643) by Wenceslas Hollar, Nuova raccolta di vari costumi di Roma (1844) by Wenceslas Hollar and fashion plates from the Regency to the Edwardian eras. It also included 100 ukiyo-e prints which depict Japanese women’s dress. Ukiyo-e prints were published in large quantities from the 17th to the 19th century as commodities for various purposes, such as souvenirs, advertisements, journalistic media and fashion plates. One of the popular subjects of ukiyo-e prints was beautiful women and were enjoyed by the people in Edo Japan who were keen to know the latest trends of kimono, accessories, hair styles and make-ups. These kinds of ukiyo-e prints must have fit the collecting principle of Bloomfiled. Bloomfiled may have never visited Japan, but it must have been easy to find and purchase ukiyo-e prints in Britain, as ukiyo-e prints were the most popular Japanese objects in the vogue of Japonisme and were exported in massive numbers to Europe and America from the mid-19th century onwards. 25 ukiyo-e prints were chosen from the Bloomfiled collection to be displayed at the 1918 exhibition.

Hosoi Tanosuke (1860–?), whose name was misprinted ‘Tonosuke’ in the exhibition catalogue, was not a local of Sussex but is worth mentioning, as he contributed greatly to the collection of Japanese objects at the Brighton Museum. He was born in Fukui, Japan, and was trained as a traditional Japanese sculptor. He went to London in order to demonstrate his skill as a sculptor at the Japanese Village produced by a Dutch entrepreneur, Tannaker Billingham Neville Buhicrosan, in 1885. He then turned dealer of Japanese arts and crafts and continued to live in London. As the diary of Minakata Kumagusu, the Japanese naturalist, biologist and folklorist who studied in London from 1892 to 1900, suggests, Tanosuke’s shop might have been near the British Museum. [12.] His surname was Hosoi or Ogawa (before he was adopted by the Hosoi family), and his first name Tanosuke. However, in Britain, Tanosuke was used as his surname and Hosoi or Ogawa as his first name. As mentioned above, Gulland called Tanosuke from London to catalogue his collection of Japanese ceramics which had been donated to the Brighton Museum around 1902. Tanosuke’s connection with the Brighton Museum must have started at that time. Tanosuke himself donated 44 ukiyo-e prints to the museum, [13.] which are still one of the major collections of ukiyo-e prints at the Brighton Museum & Art Gallery. In 1905, the descriptions on the labels of the Japanese and Chinese metalworks donated to the museum by Willett were produced with assistance of Tanosuke. [14.] The museum must have put trust in his knowledge of Japanese and Chinese art. It is reported that, in 1902, around the very time when Gulland introduced Tanosuke to the museum, Tanosuke attended a banquet held in the mansion house of Spencer Compton Cavendish, 8th Duke of Devonshire. [15.] Tanosuke might have made his acquaintance with Gulland at that time. In any case, it is intriguing to imagine how a young and resourceful Japanese man came to Britain along with other Japanese entertainers and acrobats for the show in London, rode on the tide of Japonisme, turned art dealer and, finally, developed his network not only among the Japanophiles in London but also among the luminaries around Sussex. For the 1918 exhibition, 25 prints were chosen from his collection.

Merton Russell-Cotes (1835–1921) was not a local of Sussex either, but was one of the major collectors of Japanese art in Britain. He was the owner of a hotel in Bournemouth. He visited Japan with his wife in 1885 on his travels around the world and retuned to Britain with more than 100 boxes of Japanese objects. These Japanese objects adorned a room in the hotel and gained a reputation. [16.] Russell-Cotes lent two objects from his collection for the 1918 exhibition in Brighton. These objects were described as ‘Silver and gold jewelled elephant, with children’s band and crystal ball. By Komai’ and ‘Plaque of malleable iron, heavily inlaid with gold, By Komai’, but the former is presumably the one that is now recognised as the work of Nakagawa Yoshizane. [17.] Although the number of the objects he lent was very small, Russell-Cotes seems to have chosen the finest works from his collection for the exhibition in Brighton.

The year that Russell-Cotes sailed to Japan, 1885, was the very year when the Japanese Village, for which Tanosuke sailed to Britain, opened in London. At the height of Japonisme in the late 19th century, the illusion of Japan was enhanced by people like these two who rode on the tide of Japonisme: one as a globe trotter enjoying the prosperity of the British Empire and the other as one of the entertainers who demonstrated the craftsmanship of Japan as a fairyland in the ‘Far East’. The ripples of this tide also reached Brighton in the early 20th century, when Japan was aiming to join the Great Powers in the world in reality. The objects displayed at the 1918 exhibition were offered by the people who came to have an interest in Japanese arts and crafts while travelling around Asia as well as those who never visited Japan but purchased Japanese objects in the vogue of Japonisme. The exhibition catalogue, which vividly depicts these objects, shows that, next to the Royal Pavilion as a legacy of the illusion of Chinoiserie, an illusion of Japonisme manifested itself in Brighton in 1918.

Notes:

1. Floating Worlds: Japanese Woodcuts (2019) < https://brightonmuseums.org.uk/brighton/exhibitions-displays/brighton-museum-past-exhibitions/past-exhibitions-2019/floating-worlds-japanese-woodcuts/> [Accessed 29 November 2020]

2. Public Art Galleries, Brighton, Catalogue of an Exhibition of Japanese Art, May and June 1918. Unless otherwise stated, the information about this exhibition mentioned in this blog derives from this catalogue.

3. Alexandra Loske, Robert Goff in Hove: Wick Studio, Holland Road (2012) < https://brightonmuseums.org.uk/discover/2012/02/06/robert-goff-in-hove-wick-studio-holland-road/> [Accessed 20 November 2020], Clarissa Goff – travel writer and benefactor of Brighton and Hove’s Fine Art collections (2020) < https://brightonmuseums.org.uk/discover/2020/07/29/clarissa-goff-travel-writer-and-benefactor-of-brighton-and-hoves-fine-art-collections/> [Accessed 19 November 2020].

4. Yamada Yukiko, ‘Oiso to Buraiton Dai 1 Sho “Kaisuiyoku” Gainen no Henkaku’ [Oiso and Brighton: Chapter 1: the Development of the Concept of ‘Sea Bathing’], Report: Oiso Kyodo Siryokan Dayori [Report: Newsletter of Oiso Municipal Museum], no. 29, 2009, pp. 4–6.

5. Tanita Hiroyuki, Yuibi Shugi to Japanizumu [Aestheticism and Japanism] (Nagoya: Nagoya Daigaku Shuppankai, 2004), pp. 104–108.

6. Victoria and Albert Museum, V&A Archive Research Guide: Donors, collectors and dealers associated with the Museum and the history of its collections < https://vanda-production-assets.s3.amazonaws.com/2019/05/02/14/01/30/203468f3-777f-48b1-8b7e-13551dc47462/Donors_collectors_research_guide.pdf> [Accessed 3 September 2020].

7. W. G. Gulland, Chinese Porcelain, 2 vols., third edition (London: Chapman & Hall, 1911).

8. County Borough of Brighton, Public Library, Museums and Art Galleries, Annual Report of the Chief Librarian and Curator, 1902-3, p. 26 shows his address, 30 Brunswick Terrace, Brighton.

9. Ibid., pp. 24–25.

10. Stella Beddoe, A Potted History: Henry Willett’s Ceramic Chronicle of Britain (Woodbridge: ACC Art Books, 2015), p.10.

11. Brighton & Hove Libraries Rare Books & Special Collections < https://ww3.brighton-hove.gov.uk/sites/brighton-hove.gov.uk/files/Rare%20Books%20and%20Special%20Collections%20-%20Guide.pdf> [Accessed 28 November 2020].

12. Koyama Noboru, Rondon Nihonjinmura o Tsukutta Otoko: Nazo no Kogyoshi Tanaka Buhikurosan [The Man Who Created a Japanese Village in London: Tannaker Buhicrosan, a Mysterious Impresario] (Tokyo: Fujiwara Shoten, 2015), pp. 281–284.

13. County Borough of Brighton, Public Library, Museums and Art Galleries, Annual Report of the Chief Librarian and Curator, 1902-3, pp. 24–25.

14. County Borough of Brighton, Public Library, Museums and Art Galleries, Annual Report of the Chief Librarian and Curator, 1905, p. 23.

15. Koyama, pp. 283–284.

16. Gregory Irvine, A Guide to Japanese Art Collections in the UK (Amsterdam: Hotei Publishing, 2004), pp. 24–27, Russell-Coates <https://russellcotes.com/> [Accessed 28 November 2020].

17. Irvine, pp. 25–26.

Leave a Reply