Climate. Over the past month or so I have attended a cornucopia of online lectures and events – there was the Institute of Conservation’s Book and Paper Group conference, the Archives and Records Association’s Conservation Lecture Week and The National… Continue Reading →

Let’s talk British Standards Institution and go for a bit of a version of a Throwback Thursday… Back in 2018, I had the opportunity to attend a one-day conference at the National Archives in Kew, organised by the National Conservation… Continue Reading →

So…. let’s talk news! None of us can deny that it has been a bit of a time for breaking news, ranging from the U.S. election to the COVID-19 vaccine trial success – and everything else in-between. I’ve returned to… Continue Reading →

For the past two weeks I have shifted my working-from-home to my native Finland, where I have been experiencing quarantine existence prior to being able to take some time off and see family and friends – within the restrictions in… Continue Reading →

It appears some time has passed since I last wrote anything on my beloved blog – and what a ride it’s been since the last post! A lot has changed in the Design Archives in the past two years, and… Continue Reading →

As I mentioned in my previous entry, I have a treat for you: the second guest entry on this blog! The text has been written by Textile Conservation student Emma Hartikka (also Finnish, so I get to promote Finnish know-how… Continue Reading →

At the end of January this year, we embarked upon an archival deep cleaning mission here in the Design Archives. Archival deep cleaning is not something to be taken on by one person alone but requires a minimum of two… Continue Reading →

Last week I had the fantastic opportunity to travel to Birmingham to attend a 3-day course/workshop organised by Historic England, in collaboration with the West Midlands Fire Service. The course was titled ‘Salvage and Emergency Planning’ and was made up… Continue Reading →

Within our collections, we have various books that are part of the archives we hold. Most notably FHK Henrion‘s library from his studio, which includes books in several languages on a variety of different subjects. Obviously books present a whole… Continue Reading →

As a third addition to the de Majo archive’s story, I thought I would write a post about the more non-conventional items the archive holds. In my previous post I mentioned some of these items that did not go through… Continue Reading →

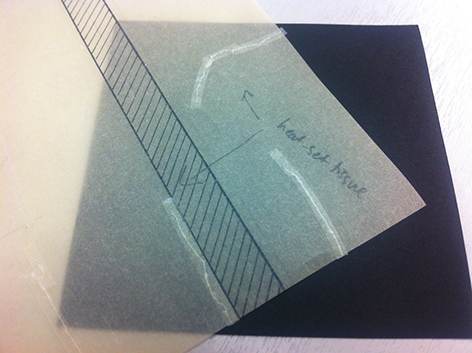

After the initial sort out of the de Majo archive in our external storage unit, the next step in the process was for all of the materials to be transported to The Keep for conservation. We have a good, collaborative… Continue Reading →

I’ve decided to take a trip back in time. This time last year I was in the middle of an undertaking to start planning the long term care of the Willy de Majo archive. Up to that point, some the… Continue Reading →

Where has all the time gone (she said for the 100th time since starting to write this blog)? Autumn is here, and what a beautiful autumn it has been so far too! I would go as far as saying that… Continue Reading →

Now felt like a good time to write a little post about some very recent goings on. The Design Archives’ Deputy Curator Dr Lesley Whitworth has curated an exhibition at the University’s Grand Parade Gallery. The exhibition is entitled ‘Design… Continue Reading →

Where do I start with this blog? Slightly nervous coming back to this after such a long absence… There have been several projects on the go after I last wrote anything, and there are always loose-ends-a-plenty hanging around to be… Continue Reading →

After a somewhat frantic effort yesterday of trying to place the mystery glass plate negatives I found, with help from various individuals we have got some results! My colleague Lucy Hermann, Sally England from Hackney Archives, Dr Andrew Jackson from… Continue Reading →

Anyone still out there…? I have not written a blog entry for a good five months, though the thought has been there on several occasions. I am attempting a come-back with a bit of a mystery to resolve – not… Continue Reading →

At the risk of stating the obvious, we are well and truly in the midst of the age of the internet – with its pros and its cons – to which the majority of people have access to and use… Continue Reading →

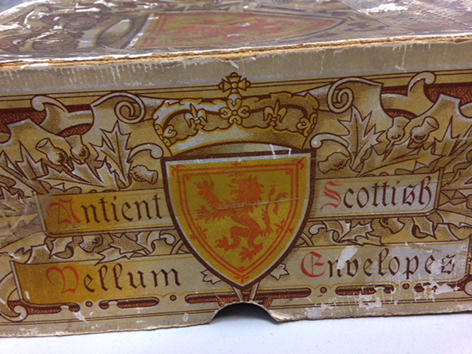

I had the chance to work with some of the oldest materials we have in our predominantly 20th Century collections – these gems originate from the 1880s/1890s and belong to the Vokins archive. This archive has a very local focus in… Continue Reading →

As my work over the past few years with the posters in the Icograda Archive is coming to an almost-but-not-quite-there-yet -end, I am starting to embark upon another long-term project working with the archive of James Gardner, who is best known for his… Continue Reading →