Social media marketing, such as on Twitter, can provide an excellent opportunity for companies to directly engage with their audience, and react quickly and strongly to changing market dynamics. However, in some cases, when not handled correctly, it provides a platform for a company’s audience to publicly lambast them, and bring a great deal of embarrassment and damage to a brand. In this blog post, we are going to explore the case of Protein World, and how they reacted to an overwhelmingly negative online conversation.

In the spring of 2015, Protein World (a supplier of workout supplements) unveiled their “Are You Beach Body Ready?” campaign, renting advertising space on billboards and trains, supplemented by postings on social media – most notably via Twitter. The campaign poster included a slender, toned, young woman donned in only a bikini, asking the audience a simple question – are you beach body ready?

The objective of the campaign was rather obvious – to inspire and encourage the audience to get in shape for the summer using their supplements. What they didn’t anticipate was the combined backlash from the recently emerging “fat-acceptance” movement (SBS, 2014), and the angry and vocal fourth-wave feminists of Twitter (Cochrane, 2013), accusing the company of objectifying and body-shaming women in a “sexist” campaign.

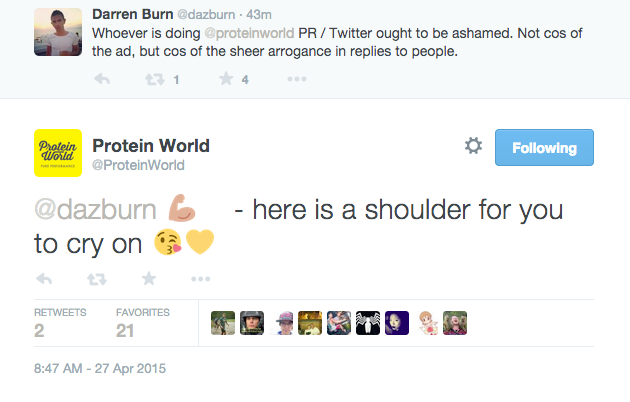

The responses to the campaign shown above beg the question, how on Earth do you respond to such a scathing backlash? Do you remain silent, or do you try to mitigate the damage through a friendly PR filter? After all, at this point the nation was watching, with the majority of major news outlets in the UK covering the story. Well, in a move that would make many marketers cringe, Protein World did neither and instead went full-force, taking to arguing with and directly insulting their critics publicly on Twitter.

This move served to contradictingly both comply with and completely subvert the findings outlined by Noort and Willemsen (2011), in which the key take-away was that companies can help to mitigate damage through responding quickly and directly to negative online conversations, while striving to “improve brand evaluations by showing that they take the problems of customers seriously”. But surprisingly, not taking customers seriously (but still taking the time to respond to them) appeared to work in their favour, with the company reportedly generating an additional £1 Million in sales as a result of the backlash (Brinded, 2015). But this raises a question difficult to answer – would they have been more successful if they hadn’t taken to insulting and marginalising a large section of the public?

To begin to answer that question, we must first ask what the KPIs of a social media campaign are. Blanchard (2011) makes the case that in a social media campaign, the performance indicators may differ depending on who is rating the campaign’s success. Marketers who focus on brand reputation may rate the success of a campaign through the amount of positive conversations in relation to the amount of negative ones, however, some marketing teams may take a numbers approach – the more shares, likes, and followers, the more successful the campaign is (Blanchard, 2011).

In relation to Protein World, if we are to take the latter approach and use a pure numbers perspective, using the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine (SocialBlade does not provide tracking for Protein World’s account) we are able to ascertain that between the 25th April 2015 when the controversy first hit, and the 28th April, the @ProteinWorld Twitter account gained an impressive 5,000 followers – increasing by another 5000 to a total of 70,000 by the beginning of June that year. In other words, in the 2 months following the campaign, they managed to increase their total number of Twitter followers by 13.24% – not too bad for what some would call a marketing blunder.

However, if we are to take the perspective of brand reputation in to account, the campaign could probably be described as an overwhelming disaster. With thousands, if not hundreds of thousands, of people insulted and distanced from the brand, with the combined might of the news media publishing scathing articles in relation to the controversy (Burrows, 2015), the campaign probably didn’t do Protein World’s reputation any good – yet the company is still operating, with more Twitter followers than ever before. So why is this the case?

This brings us to Hanna, Rohm, and Crittenden’s (2011) work. In their article, they provide 5 lessons in social media marketing – the final, and arguably most important, being “Be unique”. Their argument is that using authenticity and uniqueness gives consumers a reason to engage with the brand in the first place, which would explain why Protein World recieved the attention that they did, both positive and negative – but a least it was memorable. Would Protein World have been better off responding via Noort and Willemsen’s (2011) technique of “taking the problems of consumers seriously”, or implementing a more sensitive advertising campaign in the first place? We may never know, but it can certainly be said that the campaign made one hell of a memorable impact and helped make a name for a previously relatively obscure brand.

So did Protein World learn anything from the campaign? Did they ensure that their adverts were more sensitive and including of others? Well, no. They were back at it again with a new campaign the next year – featuring even more scantily-clad women than before (Cohen, 2016). But depending on who you ask, in an age where people are demanding more authenticity from public figures (Kanski, 2016), this type of PR may well continue to work in their favour.

For more on social media controversies, be sure to click here.

References:

Blanchard, O. (2011). Social media ROI. 1st ed. Indianapolis, Ind.: Que.

Brinded, L. (2015). Protein World makes £1 million immediately after the ‘Beach Body Ready’ campaign backlash. [online] Business Insider. Available at: http://uk.businessinsider.com/protein-world-makes-1-million-immediately-after-the-beach-body-ready-campaign-backlash-2015-4?r=US&IR=T [Accessed 28 Feb. 2017].

Burrows, T. (2015). ‘Beach body ready’ named as Britain’s WORST advert of 2015. [online] Mail Online. Available at: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3356137/The-festive-turkeys-no-one-s-buying-Beach-body-ready-named-Britain-s-WORST-advert-2015-Kelly-Brook-Ferne-McCann-s-terrible-acting-not-far-behind.html [Accessed 28 Feb. 2017].

Cochrane, K. (2013). The fourth wave of feminism: meet the rebel women. [online] The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2013/dec/10/fourth-wave-feminism-rebel-women [Accessed 28 Feb. 2017].

Cohen, C. (2016). Protein World is back with a new body shaming ad – and it’s more sexist than ever. [online] The Telegraph. Available at: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/women/life/protein-world-is-back-with-a-new-body-shaming-ad—and-its-more/ [Accessed 28 Feb. 2017].

Hanna, R., Rohm, A. and Crittenden, V. (2011). We’re all connected: The power of the social media ecosystem. Business Horizons, 54(3), pp.265-273.

Kanski, A. (2016). Change and authenticity: The messages that won over American voters. [online] Prweek.com. Available at: http://www.prweek.com/article/1415125/change-authenticity-messages-won-american-voters [Accessed 28 Feb. 2017].

Noort, G. and Willemsen, L. (2012). Online Damage Control: The Effects of Proactive Versus Reactive Webcare Interventions in Consumer-generated and Brand-generated Platforms. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 26(3), pp.131-140.

SBS. (2014). Fat pride: The growing movement of people looking for fat acceptance. [online] Available at: http://www.sbs.com.au/news/thefeed/story/fat-pride-growing-movement-people-looking-fat-acceptance [Accessed 28 Feb. 2017].