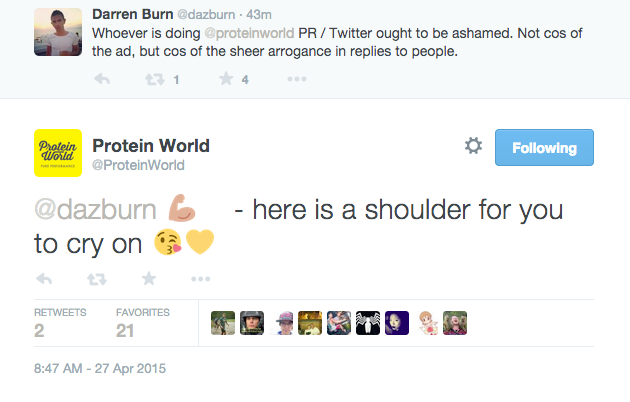

Over the past few posts, we’ve explored instances in which brands have failed to meet the mark, and struggled to resonate with much of their target audience, as was the case with Protein World’s ‘Beach Body Ready’ campaign and the ‘Boaty McBoatface’ fiasco. However, whilst it is indeed important to learn from these arguable failures, it is perhaps of greater importance to explore instances in which brands have succeeded in resonating with their target audience through social media.

The inherent openness that stems from social media platforms can present brands with a great opportunity to not only meet or exceed the expectations of a single customer, but also presents a further opportunity for the content to go viral – providing the brand with a cheap, quick, and effective way to reach a global audience. In this final post, we are going to explore the recent case of Wendy’s, and how an accidental marketing campaign broke Twitter records.

Wendy’s

Wendy’s, for those that don’t know, is a fast food chain operating within the United States. Therefore, you wouldn’t be blamed for assuming that their Twitter page would simply be a plain, boring platform, in which the posts largely revolve around publicising their latest sales promotions and answering customer support requests, akin to the likes of Pizza Hut (Pizza Hut, 2017) or Subway (Subway, 2017). Yet, whilst there are indeed some of the more ‘vanilla’ posts being made via Wendy’s Twitter account (Wendy’s, 2017), the person (or people) behind the account is no stranger to taking the opportunity to inject some personality in to their posts, quickly becoming a hit with the largely millennial demographic of Twitter (Ngo, N.d.).

Enter Carter Wilkerson (Wilkerson, 2017), a teenage Twitter used based in Reno, Nevada. Carter, seemingly eager for the opportunity to barter for some free chicken nuggets from Wendy’s, sent a tweet to their account requesting how many retweets would be required in order to bag a free year’s worth of nuggets from the fast food chain. In response, Wendy’s adopted their usual mischievous tone and set a seemingly impossible goal of 18 million retweets – a figure that would surpass the then most retweeted post of all-time (Smith, 2014) by around 500%.

Whilst a lot of people at this point would concede, Carter instead used this opportunity to launch a Twitter campaign of his own, supported by the #nuggsforcarter hashtag. And of course, the story quickly went viral across both Twitter and the news media, with a seemingly unending number of publications picking up the story and promoting his cause (Molloy, 2017; Independent, 2017) – even gaining the support of celebrities along the way:

The publicity machine was at this point churning at full speed, providing the ‘snowball effect’ (Goode, 2009) that helps spur content to become viral. Now, just one month later, Carter and Wendy’s have broken the record for the world’s most retweets (Stephenson, 2017), at over 3.55 million at the time of writing (Wilkerson, 2017).

Whilst Carter hasn’t quite met his target, Wendy’s were presumably very satisfied with this record-breaking result, giving the teen his much-deserved year’s supply of chicken nuggets, as well as donating $100,000 to The Dave Thomas Foundation, a charity that Carter supported throughout his campaign (Wendy’s, 2017).

The Metrics

After all this commotion, what does this actually mean for Wendy’s? Well, in a period of just one month, their Twitter account managed to gain over 240,000 followers during the span of the #nuggsforcarter campaign, increasing the number of followers by 15% to bring them to a total of 1.82 million from 1.58 million (Wendy’s, 2017).

Furthermore, Wendy’s continued support of Carter enabled them to generate thousands of likes and retweets across each of their posts that made reference to the campaign. As well as Wendy’s increasing their own amount of followers and helping to break Twitter records, they also benefited from the free publicity provided by the news media, with major news sites such as Forbes and the New York Times following the story until its conclusion (Stark, 2017; Victor, 2017) .

Lessons to be Learned

So why did this event resonate so well with their audience? Well, it is first important to establish just who Wendy’s Twitter audience are. A study from the Pew Research Center identified that the most likely demographic to use Twitter are indeed young adults, aged 18-29 (Duggan and Brenner, 2012), placing this audience closely within the millennial generation bracket. Now that this has been ascertained, we can begin to explore why they may have responded so well to this event.

Palfrey and Gasser (2011) describe millennials as being:

“Joined by a set of common practices, including the amount of time they spend using digital technologies, their tendency to multitask, their tendency to express themselves and relate to one another in ways mediated by digital technologies, and their patterns of using the technologies to access and use information and create new knowledge and art forms” (Palfrey and Gasser, 2011).

Furthermore, several studies have been conducted on millennial behaviour in both high school and college classes, with most concluding that millennials largely reject authority, relate well to humour and technical prowess, and possess a strong sense of community among their peers (Berenson, 2008; Price, 2010; Klice, 2010).

Wendy’s seemingly hit the mark on all the criteria, using humour and relatability to address their audience and promote Carter’s cause. Furthermore, the content and language of Wendy’s Twitter posts is largely indistinguishable from the audience themselves, and implies an-almost anti-authoritarian approach through breaking the preconceived notions of the content expected from a multi-billion dollar company. This helps to create a sense of irony, and could encourage the audience to accept the person running the account as one of their own, consequently becoming more willing to engage with the content.

Cases like this potentially signify a changing digital marketing landscape. Perhaps, in the future, there may be less reliance on a strong, planned, social campaign, and instead companies could begin to embrace user-created, organic campaigns in the hopes of increasing engagement and relatability with their audience. After all, what better way to create relatable content than having your audience create it themselves?

For more sassy corporate Twitter accounts, click here.

References:

Berenson, S. (2008). Educating Millennial Law Students for Public Obligation. 1st ed. [ebook] San Diego: Charlotte Law Review. Available at: https://poseidon01.ssrn.com/delivery.php?ID=399000101024080086090012092123017085052064046049049050078074022092000066004094116023037114102042000002119104002064020000082094021017027075017072083083095066125077048058010029019069121068094095023081096118127124026125095030107122094119070010020000121&EXT=pdf [Accessed 10 May 2017].

Duggan, M. and Brenner, J. (2012). The Demographics of Social Media Users – 2012. 1st ed. [ebook] Washington, DC: Pew Research Center’s Internet & American Life Project. Available at: http://www.nwnjsbdc.com/upload/PIP_SocialMediaUsers%20Demographics%202012.pdf [Accessed 10 May 2017].

Goode, L. (2009). Social news, citizen journalism and democracy. New Media & Society, 11(8), pp.1287-1305.

Independant (2017). A teenager’s request for chicken nuggets is going viral. [online] The Independent. Available at: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/nuggs-please-chicken-nugget-teenager-charlie-wilkerson-twitter-request-retweets-millions-a7678516.html [Accessed 10 May 2017].

Kice, B. (2010). Humorous Commercials, Millennial Students, and the Classroom. Texas Speech Communication Journal Online. [online] Available at: http://www.etsca.com/tscjonline/0810-commercials/ [Accessed 10 May 2017].

Molloy, M. (2017). Student makes ridiculous Twitter bet for free Wendy’s chicken nuggets. [online] The Telegraph. Available at: http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2017/04/08/student-makes-ridiculous-twitter-bet-free-wendys-chicken-nuggets/ [Accessed 10 May 2017].

Ngo, H. (n.d.). Wendy’s Is Roasting People On Twitter, And It’s Brutally Funny.. [online] LifeBuzz. Available at: http://www.lifebuzz.com/wendys-twitter/ [Accessed 10 May 2017].

Palfrey, J. and Gasser, U. (2011). Born Digital: Understanding the first generation of digital natives. 1st ed. Sydney: Read How You Want.

Pizza Hut (2017). Pizza Hut (@pizzahut) | Twitter. [online] Twitter.com. Available at: https://twitter.com/pizzahut [Accessed 10 May 2017].

Price, C. (2010). The New “R”s for Engaging Millennial Learners. Essays from E ‐ xcellence in Teaching, [online] 9, pp.29-31. Available at: https://teachpsych.org/Resources/Documents/ebooks/eit2009.pdf#page=29 [Accessed 10 May 2017].

Smith, C. (2014). Ellen DeGeneres’ Oscars selfie smashes Obama retweet record on Twitter. [online] the Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/film/2014/mar/03/ellen-degeneres-selfie-retweet-obama [Accessed 10 May 2017].

Stark, H. (2017). Carter Wilkerson: The Nuggets Guy Who Broke Twitter. [online] Forbes.com. Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/haroldstark/2017/05/03/carter-wilkerson-the-nuggets-guy-who-broke-twitter/#199846956ab4 [Accessed 10 May 2017].

Stephenson, K. (2017). Nuggs For Carter breaks Ellen’s Twitter retweets world record. [online] Guinness World Records. Available at: http://www.guinnessworldrecords.com/news/2017/5/nuggs-for-carter-breaks-ellens-selfie-world-record-471254 [Accessed 10 May 2017].

Subway (2017). SUBWAY® (@SUBWAY) | Twitter. [online] Twitter.com. Available at: https://twitter.com/subway [Accessed 10 May 2017].

Victor, D. (2017). Step Aside, Ellen DeGeneres: The New Retweet Champion Is a Nugget-Hungry Teenager. [online] Nytimes.com. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2017/05/09/technology/wendys-nuggets-twitter.html?_r=0 [Accessed 10 May 2017].

Wendy’s (2017). Wendy’s on Twitter. [online] Twitter. Available at: https://twitter.com/Wendys/status/861642615569223680 [Accessed 10 May 2017].

Wendy’s (2017). Wendy’s on Twitter. [online] Twitter. Available at: https://twitter.com/Wendys/status/861938018806095872 [Accessed 10 May 2017].

Wilkerson, C. (2017). Carter Wilkerson (@carterjwm) | Twitter. [online] Twitter.com. Available at: https://twitter.com/carterjwm [Accessed 10 May 2017].

Wilkerson, C. (2017). Carter Wilkerson on Twitter. [online] Twitter. Available at: https://twitter.com/carterjwm/status/849813577770778624 [Accessed 10 May 2017].