Tristram Hunt, author of a very readable and well researched biography of Engels, has written a timely piece on Friedrich Engels – ‘one of Britain’s greatest emigres’ – for the Observer – Engels comes of age: the socialist who wanted a joyous life for everyone – it is well worth a read in full – but some highlights are here:

This month marks the 200th anniversary of the birth of the Rhinelander turned reluctant Mancunian turned old Londoner. Always happy to play “second fiddle to so splendid a first violin” as Karl Marx (“How can anyone be envious of genius; it’s something so very special that we, who have not got it, know it to be unattainable right from the start?”), he deserves so much more than just being cast as history’s supporting man…

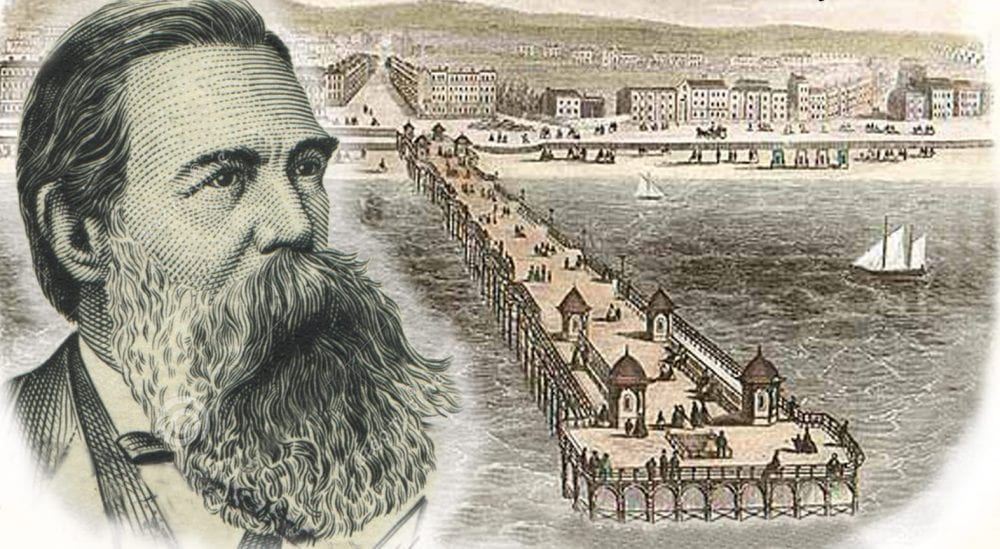

Born on 28 November 1820 in Barmen, along the Wupper Valley, in Prussia, Engels grew up as the scion of a strictly Calvinist, capitalist, and suffocatingly bourgeois family of textile merchants. His was a loving childhood of plentiful siblings, family wealth and communal cohesion in what was termed “the German Manchester”. But from an early age Engels found the human costs of his family’s prosperity hard to bear. Aged only 19, he wrote of the plight of factory workers “in low rooms where people breathe in more coal fumes and dust than oxygen”, and lamented the creation of “totally demoralised people, with no fixed abode or definite employment”.

After falling under the spell of the Young Hegelians at Berlin University it was 1840s Manchester that turned him towards socialism. Sent to work at the family mill in Salford in the epicentre of the industrial revolution, he saw how unregulated capitalism entailed sustained dehumanisation: “Women made unfit for childbearing, children deformed, men enfeebled, limbs crushed, whole generations wrecked, afflicted with disease and infirmity, purely to fill the purses of the bourgeoisie,” as he put it in his masterwork, The Condition of the Working Class in England (1845).

What Engels also brilliantly revealed in this book was how urban planning and regeneration were arenas for class conflict. He is the father of modern urban sociology, explaining in ways in which we are only now familiar how city space is always socially and economically constructed. Today’s commentators on the privatisation of public space or Mike Davis’s work on our Planet of Slums all exist in the shadow of Engels’ pioneering critique of industrial Manchester…

It was Engels’s popularisation of Marx’s central insights in his pamphlets Anti-Dühring and Socialism: Utopian and Scientific, that launched Marxism as a compelling global creed… After Marx’s death in 1883, Engels enjoyed the freedom of expanding Marx’s thinking in new directions. In his study of the history of family life, Engels laid the foundations for socialist feminism with his connection of capitalist exploitation to gender inequality. Similarly, Engels pioneered the Marxist vision of colonial liberation with his early analysis of imperialism as a core component of Western capitalism. From Vietnam to Ethiopia, China to Venezuela, Engels’s theory of emancipation was adopted by anti-imperial freedom fighters, even as the Soviet empire deployed him to expand across eastern Europe.

Engels was a figure of profound historical and philosophical significance. Yet what I discovered, as his biographer, was that his vision of socialism could also be richly uplifting: the grisly, corrupt, anti-intellectual egalitarian Marxism of the 20th century would have horrified him. “The concept of a socialist society as a realm of equality is a one-sided French concept,” he said. Instead, Engels believed in cascading the pleasures of life – food, sex, drink, culture, travel, even fox-hunting – across all classes. Socialism should not be a never-ending Labour party meeting, but a life of enjoyment. The real challenge of living in Manchester was that he could find no “single opportunity to make use of my acknowledged gift for mixing a lobster salad”…