Eastbourne has a wider and longer connection to radicalism than simply Friedrich Engels – and as part of our series on Radical Eastbourne we will begin to outline some of this rich ‘hidden history’.

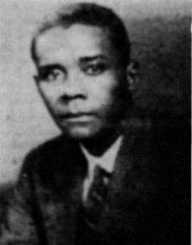

C.L.R. James visits Eastbourne to report on a critical cricket clash between Lancashire and Sussex

In August 1934, the black Trinidadian Marxist writer and historian C.L.R. James – later author of classic works such as The Black Jacobins (1938) about the Haitian Revolution (which was partly written up in Southwick) and Beyond a Boundary (1963) – about West Indian cricket – visited The Saffrons, Eastbourne in his capacity as a cricket reporter for the Manchester Guardian to cover the critical county cricket clash between Lancashire and Sussex, with both sides hopeful of winning the championship that season.

‘Before the match between Lancashire and Sussex could begin at Eastbourne the rain came down; luncheon was taken at one o’clock, and play started at two. During the delay many spectators walked to the centre of the ground, stood round the protecting ropes, and stared solemnly at the pitch for minutes on end. There was nothing to be seen on its virgin surface. What could there be? But this was a real championship match and had the championship atmosphere…’ James describes the clash between Sussex bowler Maurice Tate and Lancashire batsman Ernest Tyldesley ‘it was a day’s watching to see these two striving with one another, knowing that from the result of this duel a championship might be won or lost; Tate genial but deadly, Ernest graceful but dour, steel rasping against steel… ‘ (‘Lancashire in Difficulties’, Manchester Guardian, 23 August 1934)

With Lancashire making 196 in their first innings, on the second day, ‘during the interval the sun shone out nobly and the Sussex crowd came pouring in, so that when the game began again the ground was packed close with excited people, hoping that the wicket would improve and Sussex retrieve the position … when Tate came in last Sussex had scored only 106, but Tate at once stood back and with a back stroke than which nothing finer had been seen in the match forced Pollard past cover. He was rarely in any difficulty; he made easy strokes to suit the particular balls bowled. Then he lifted a no-ball from [Dick] Pollard to the screen, hooked the next ball for four, and lifted the next clean over the crowd at long-on for six. He stole a humorous single and pretended to steal another. To make Adam and Eve laugh, the elephant “wreathed his little proboscis,” the most that Milton could bring himself to say. The Sussex crowd, more easily amused, laughed uproariously at Tate’s elephantine gamboilings. Pollard had him unexpectedly leg-before-wicket, and Sussex ended 53 behind.’ (Lancashire’s first innings lead’, Manchester Guardian, 24 August 1934).

Lancashire then dug on for the draw on the final day, with good displays of batting again, and as James notes ‘a malicious observer might have thought that the gloom of the Sussex crowd during the early torpidity was due to the fact that Sussex were losing the championship. No such thing; when [Eddie] Paynter and Tyldesley were going in their reception by crowd and pavilion alike could not have been exceeded at Old Trafford. It was only a little cricket that the crowd wanted … [Peter] Eckersley declared with his score at 321 for eight, leaving Sussex 375 runs to get in a hundred and sixty five minutes, which is absurd. The afternoon ended in peace and tranquillity. That Lancashire should decide two hours before the end of the second day’s play to freeze out the match has met with a harsh reception. Their reputation in the South is already not good … tomorrow they go to the Oval, committed to do everything else except secure a finish; the prognostications of the nightmare of boredom are bitter and sincere. Still, a championship is a championship, but the only justification for this timidity will be success. Should Surrey defeat Lancashire, and Sussex beat Yorkshire, not only Sussex but the whole of the south coast will chuckle till next season’ (Lancashire’s cricket to arithmatic’, Manchester Guardian, 25 August 1934). In the event, Lancashire did hang on to successfully take the championship title in 1934.