MA History of Design and Material Culture graduate Sandy Jones reflects on the study stages and career steps that led to a curatorial role in the Design, Architecture and Digital Department at the Victoria and Albert Museum.

I had arrived early and wandered through the cast courts at the V&A. Passing time before the meeting with curators, I paused to take a photo of an intricate stonework frieze for a friend, texting it with the words, ’can’t believe it, working here’. The brief for the job was exciting: a three month curatorial research project to explore the design history of an everyday manufacturing material, working alongside another researcher who would, in parallel, identify the objects in the museum’s collection to tell the story. It also involved looking through an entirely different lens at a collection close to my heart, the Jobbing Printing collection of commercial print at the National Art Library, to find the contextual objects that would best illustrate the material’s cultural significance and use. This early stage scoping research was a proof of concept exercise: ‘what was the story, did the museum have the objects to narrate it and were there opportunities to reframe the way we think about this material?’ I reflected that my BA/MA study had, of course, enabled me to apply for this role yet there were other factors too: field specialisation, volunteering, the encouragement of tutors and colleagues, and right place/right time opportunities.

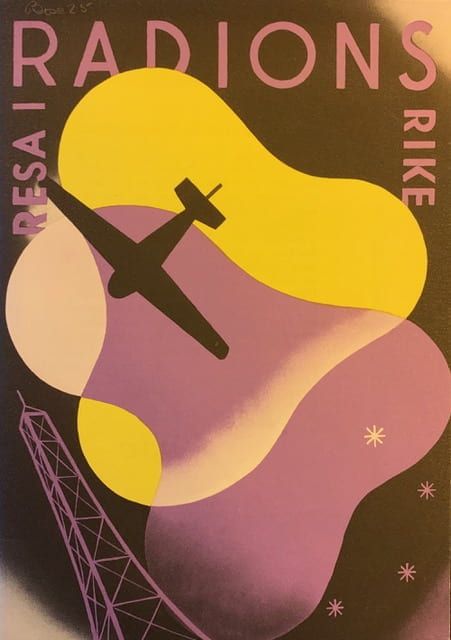

Fig. 2: Luxor Radio, Sweden, publicity material. 1930s. JP Box 25. V&A National Art Library Jobbing Printing Collection.

My interest in graphic design began when I worked in the design industry. As my Museum and Heritage Studies BA progressed I became particularly interested in design during the interwar period. Lectures such as Jonathan Woodham’s ‘American Design Between the Wars’ in 2012 (my notes to this lecture: ‘Streamlining. Speed whiskers. Aerodynamic corners. Faster, better’) brought into sharp focus how artists and designers were imagining this brave new material world. Commercial art, as it was called then, also underwent a radical transformation as modernist designers embraced new technologies such as photography and print production processes, and organisations began to recognise its value as a powerful tool for business and recovery following the Depression. An assignment to research an exhibition display from Britain Can Make It (V&A, 1946) extended my interest even further to the post war period and led me to discover the University of Brighton Design Archives. It was here that I found photographs recording the wartime exhibitions of emigré designer F. H. K. Henrion for the Ministry of Information and US Office of War Information, which became my dissertation topic.

Fig. 3: Aerobics at the De La Warr Pavilion. The People’s Pavilion: Our First 80 Years (2016). Photograph: Bexhill Observer, September 1983. Image: B2226/22. Courtesy: DLWP/Bexhill Museum.

I began volunteering early on in my BA to gain experience of working in the cultural sector and was briefly a gallery assistant at The Towner and a volunteer at the Design Museum, responsible for cleaning and packing objects for their move from Shad Thames to Kensington. I was also a regular volunteer at the iconic modernist building by the sea, the De La Warr Pavilion in Bexhill. Whilst there, I wrote the gallery guide for a Hayward Touring exhibition, helped out with admin and co-curated an exhibition, The People’s Pavilion: Our First 80 Years (2016).

Fast forward to the first term of my part-time History of Design and Material Culture MA when the DLWP asked me to undertake curatorial research for their exhibition, The New Line Works: from the Jobbing Printing Collection (2016/17). A collaboration with the V&A’s National Art Library (NAL), the exhibition showcased some of the treasures from this commercial art collection assembled by Keeper of the Library, Philip James, between 1936-39. On display were works by some of the most prominent international designers of the period, such as Edward Bawden, Barnett Friedmann, Edward McKnight Kauffer, Herbert Matter, László Moholy-Nagy and Serge Chermayeff, the joint architect of the Pavilion.

Fig. 4: Installation shot, ‘The New Line: Works from the Jobbing Printing Collection’ (2016/17). De La Warr Pavilion. Photographer: Nigel Green. Courtesy: dlwp.com.

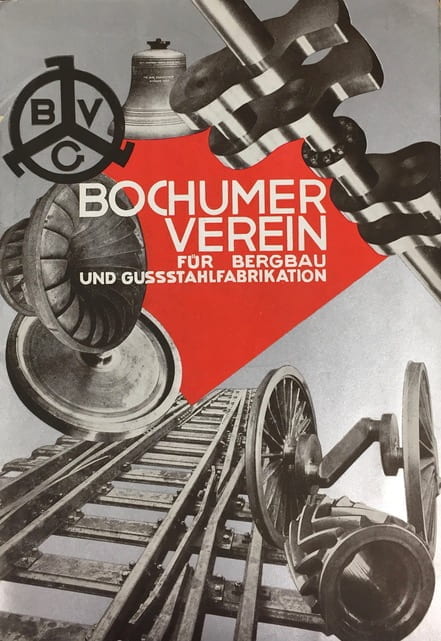

Once I’d completed this research, I knew I wanted to continue and hoped to make it my dissertation topic. I wrote to NAL curator Deborah Sutherland to ask whether there were aspects of the collection that would benefit from research. She generously invited me into the NAL to discuss three proposals. One in particular stood out, a collection within the collection containing rare Czech, German, Russian and Swiss works sold to the library by exiled German typographer and educator Jan Tschichold in 1937. It was significant as the only collection purchased for Jobbing Printing at a time when the museum did not actively collect Modernist material. I was also fortunate because Professor Jeremy Aynsley, my dissertation tutor, knew the collection well, having written about it in 1995 and exhibited works from it.

Fig. 5: Bochumer Verein publicity material, ca. 1925. Designer: Max Burchartz. JP Box 34 (a). Museum Number: 38041800366916. V&A National Art Library Jobbing Printing Collection.

In order to gain access to the objects I was sponsored by the NAL as a volunteer, this took a few weeks of paperwork relays and security checks. Even though I completed my MA dissertation in 2018, I have continued as a volunteer researcher whilst working part-time, cataloguing the works and contributing a blog post about one of its objects, a ticket to the party to inaugurate the Bauhaus school’s new buildings in Dessau, 1926. The collection continues to surprise us. Having shared a research presentation I gave at the Bard Graduate Center with the NAL team, a colleague discovered Philip James’ works list for his exhibition, Modern Commercial Typography (V&A, 1936/37), the catalyst for the Jan Tschichold purchase. This was such a find. Previously we had relied on press articles to tell us what he had displayed; finally we knew for certain.

The opportunity to work as a curatorial researcher for the Design, Architecture and Digital Department (DAD) at V&A was advertised in 2019. The role was a part-time job share and I was responsible for design history research and uncovering some of the more unusual stories. My research partner was John Williams, Collections Moves Officer who was seconded from the Blythe House Decant to identify the objects in the collection that would best illustrate this narrative. We met on Tuesdays in the research department and used WhatsApp to share images, research and snippets we had discovered. I used the online resources of the museum and accessed contemporary journals, images and texts in the NAL and St Peter’s House Library to understand the cultural context. We met regularly with senior curators Corinna Gardner and Johanna Agermann Ross, who provided direction and urged us to be critical. We visited specific exhibitions in order to analyse curatorial approaches and provoke questions about the different viewpoints we might take.

Fig. 6: Dunlop advertisement. The Illustrated London News, July 9, 1938. St Peter’s House Library, University of Brighton.

My deliverable was a timeline, report and slide presentation; John’s was a detailed object list containing images and descriptions. We shared our presentations with the team together with an online repository of our resources that John coordinated. What would I do differently next time? Set clearer parameters. With a subject so broad and endlessly fascinating, it was at times overwhelming. Working together remotely worked really well, although more face time would have perhaps produced a more unified final presentation.

I look forward to returning to the museum as an occasional volunteer when it re-opens, it will be great to see the team and Jobbing Printing. Having this project on my CV will be a great talking point as I continue to pursue other opportunities and personal research interests.

This post originally appeared on the UoB History of Art and Design blog: http://blogs.brighton.ac.uk/hoad/

Leave a Reply