Black Panther is a step in the right direction and a diverse audience is hungry for more inclusive roles and storylines

Alex Fitch, University of Brighton

From Doctor Strange: In the Multiverse of Madness to the recent She-Hulk: Attorney at Law, comics and their adaptations or spin-offs are big business. The just-released Black Panther: Wakanda Forever earned an astonishing US$330 million worldwide (£278 million) in its opening weekend.

US comics and graphic novels, meanwhile, made US$600 million in 2021 – 36% more than the previous year. And four of the most popular films of 2022 are based on comics – with the Black Panther sequel joining the top ten a week after release.

These days more and more comics are featuring a diverse range of performers and roles. In Marvel’s Loki, for example, the God of Mischief is bisexual, while the Black Panther films and the animated Spider-man movies have people of colour as their leads.

There’s also been the introduction of new characters to bridge the diversity gap, such as Ms Marvel, played by Kamala Khan and America Chavez played by Xochitl Gomez. Ms Marvel’s Muslim faith has been well received and seen as a “gamechanger” for depictions of the religion on screen.

Queering characters

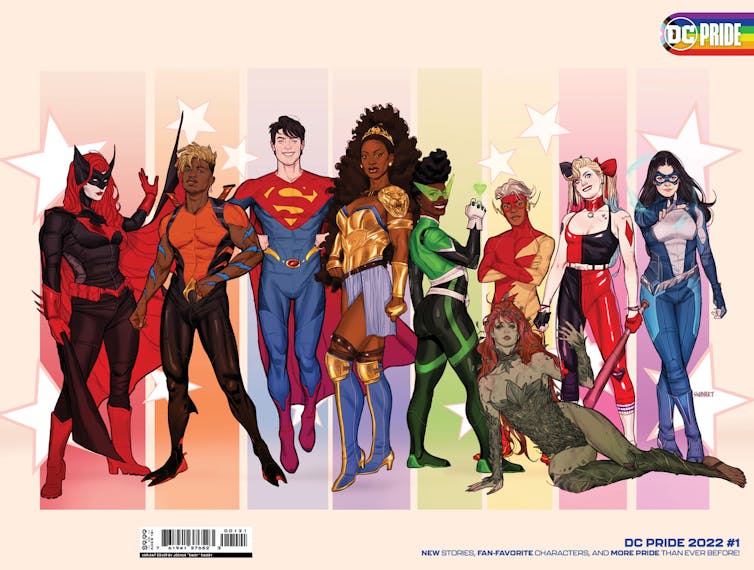

Both Marvel and DC have massively increased LGBTQ+ representation onscreen and in comics in recent times. Though a notable difference is that Marvel’s LGBTQ+ superheroes are mainly new characters, whereas DC has changed the sexuality of older characters.

Marvel’s Young Avengers, for example, has long featured a large number of LGBTQ+ characters. And DC recently created a bisexual narrative for Superman’s son, Jonathan Kent – though he is still presented as straight in the current TV adaptation.

DC also recently changed another previously straight character, the third male Robin, Tim Drake, to have him attracted to another man. Meanwhile Aquaman’s teen protege, Aqualad, was changed from a straight white teen to a gay black teen – first in an animated TV series and then in comics.

DC.com

Back in 2012, there was also the marriage of Northstar, a fairly minor member of the X-Men, to his non-white husband, which led to positive reviews. And in the same year, the original Green Lantern came out as gay.

Some fans criticised how this was handled – not only was it suggested he had been in the closet for years, but rather than giving him a life-affirming storyline, the third issue to feature a younger version of the Green Lantern character saw his boyfriend killed in a train crash.

What readers want

When it comes to diversity, Marvel has had mixed responses from some employees. In 2017 for example, David Gabriel, Marvel’s senior vice president of print, sales and marketing, said “people didn’t want any more diversity … (or more) female characters,” but later dialled back his comments, adding “we are proud and excited to … reflect new voices and new experiences.”

In terms of readers, it seems that while changes to existing characters are not so welcome,

diversity in newer storylines is seen as a positive thing.

Indeed, as academic, Jos van Waterschoot, puts it: “fandom gatekeepers may be hostile to newcomers”. Perhaps for some fans, a previously straight character feeling same-sex attraction is a step too far, even if belatedly coming out of the closet is hardly new.

DC.com

But while narrative changes to comics may lead to unwelcome criticism if long-lasting characters are killed off or have their characterisation changed, when done well it adds to the storyline – and is welcomed by fans.

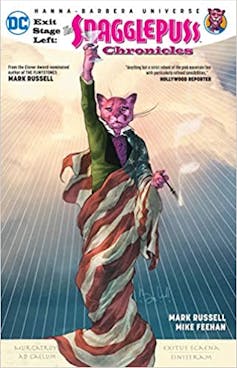

Writer, Mark Russell, for example, is noted for reviving cartoon characters in comics and giving them an LGBTQ+ twist. One of his celebrated creations, The Snagglepuss Chronicles, reimagines the Hanna-Barbera cartoon character, Snagglepuss, as a gay US playwright in the 1950s being victimised under McCarthyism.

DC.com

But more needed

At least the inclusion of new positive diverse characters seems to be leading to new readers picking up titles – with Australia’s ABC News noting a “thirst for more inclusive works”.

That said, comics have been accused of being a medium that gives the illusion of change, when often they are just trying out various combinations of the same characters in different roles – and so ultimately still end up resetting the status quo at the end of storylines.

Either way, even though LGBTQ+ and minority representation is improving on screen and in comics, there’s still a way to go in the push for diverse characters. Especially so given that straight, white men still feature strongly on the page and behind the scenes in terms of industry employees.

It’s great that many comics are now more representative of the people who actually read them, but with a recent study noting 13% of Marvel fans are Black and 18% Hispanic – and this not currently depicted on the page – it’s clear there’s room for more diversity when it comes to our superheroes.

![]()

Alex Fitch, Lecturer and PhD Candidate in Comics and Architecture, University of Brighton

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. Published: November 23, 2022 5.05pm GMT

Read Alex’s other articles in The Conversation:

Leave a Reply