In April Julian Caddy, Managing director of Brighton Fringe, caused what seemed to be a ‘local’ argument about Brighton’s Palace Pier by stating to the press that the pier ‘is a blot on the seafront that perpetuates a culture that brings Brighton down and entrenches its reputation as a cheap, out-of-date seaside destination’ (The Argus).

In April Julian Caddy, Managing director of Brighton Fringe, caused what seemed to be a ‘local’ argument about Brighton’s Palace Pier by stating to the press that the pier ‘is a blot on the seafront that perpetuates a culture that brings Brighton down and entrenches its reputation as a cheap, out-of-date seaside destination’ (The Argus).

The people of Brighton were of course quick to rebut these negative remarks about their pier and the Brighton Fringe director has come under a lot of criticism.

‘[Caddy’s] piece betrayed the dark side of gentrification when it sneered at the “parades” of people headed for the pier’s amusement arcades “via Sports Direct and Primark on their way back to their coaches”’ (Nick Norton, The Guardian).

What is clear from the ensuing debate is that it would be a mistake to underestimate the attachment communities have to their local pier (which Caddy clearly did…). The evidence of our emotional attachment to seaside piers can, for example, be found in the collected personal testimonials and anecdotes that visitors have written down on postcards at the Pierdom photography exhibitions (by Simon Roberts) around the country.

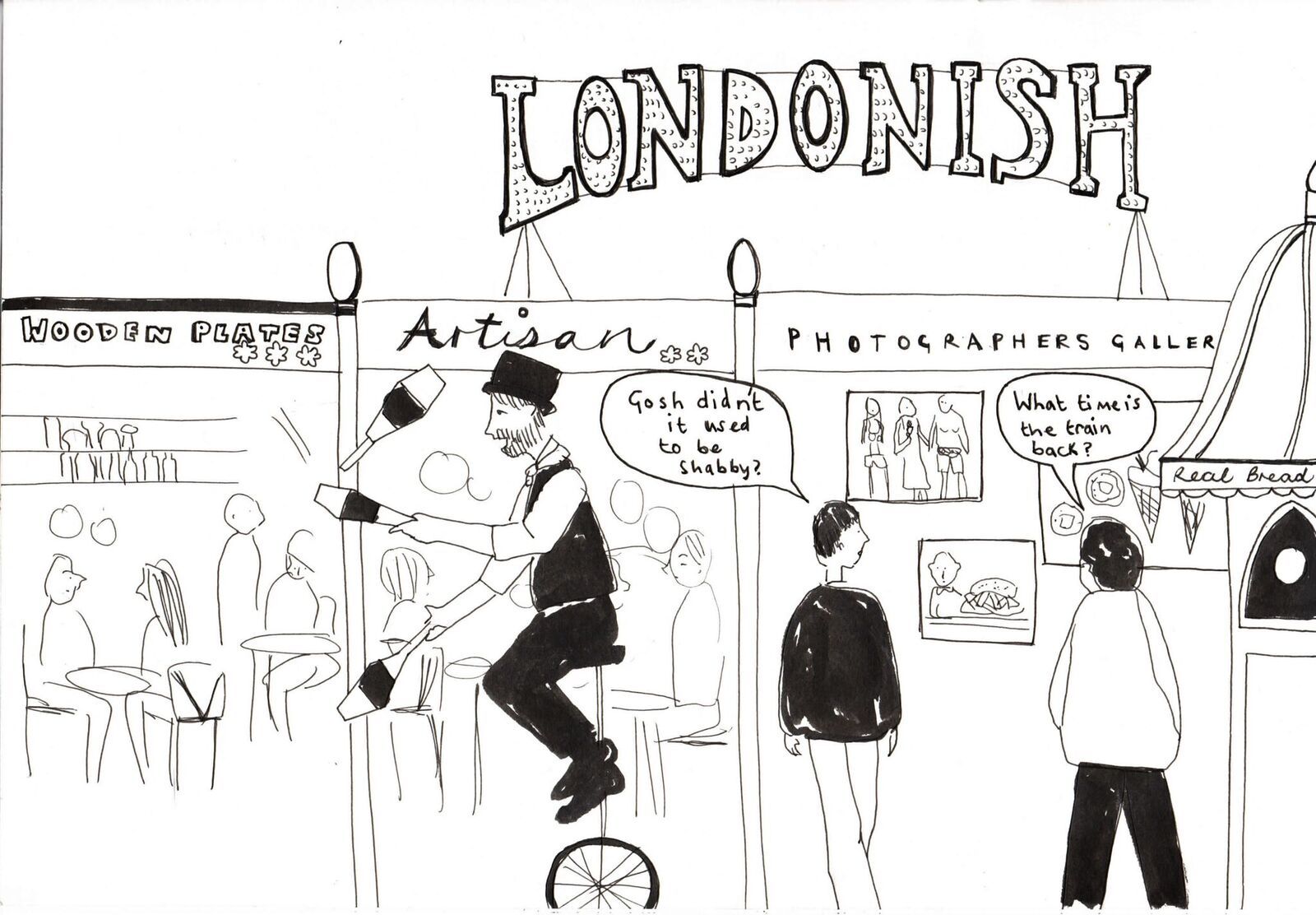

Caddy’s divisive remarks are interesting for several reasons. They typify, of course, pervasive class snobbery often expressed in terms of having or not having ‘good taste’. In his comments he paints a picture Brighton as tale of two cities: ‘the inland one of vibrant creative industries, modern restaurants and a dynamic population – and the seafront of tacky sideshows, fish and chips, rock and assorted paraphernalia.’ This not only illustrates how leisure consumption functions as a form of social stratification, in Bourdieu’s terms, but also speaks to the current issue of cultural regeneration of seaside towns that is fraught with class politics.

The people’s pier project investigates the pleasure pier as a potentially germane focus point for community engagement and cohesion, but also as a contested space. In the case of Hastings Pier our research has found plenty of indicators of the positives with a community pier – the community shareholders are central to this but the idea of the pier as a community asset and the attachment that people have with the pier may be even more important. However, community participation is a complex and shifting process. A venture like a community pier thus brings with it an array of ambiguous relationships and competing agendas that reflect ‘inequalities of resources and power’ (Cairns 2003).

Researchers critiquing arts led regeneration strategies (see Griffiths 1993:41) have concluded that such strategies are bye and large ‘congruent with the consumption preferences of the culturally dominant and politically influential’ middle class. Here ‘the people’s pier’ – as part of a wider costal town regeneration – clearly offers something of value to counter such hegemonies. Furthermore, heritage, it has been argued, can encourage participation in ‘cultural life’ and thus potentially counter or alleviate social exclusion initiatives (Newman & McLean 1998), but this raises new questions about what that cultural life in this sense might be. The popular culture heritage of pleasure piers offers a valuable and different take on the dominant notion of both ‘heritage’ and ‘cultural life’. This is why it is important that communities are given the opportunity to engage with this heritage.

The research project has also found examples of how locals resist the perceived gentrification of Hastings pier (expressed through concerns over how expensive everything on the new pier will be; a dislike of the modern architecture; and general concerns about re-purposing the pier), again demonstrating how leisure consumption relates to social stratification and how the pier is a culturally contested space.

But we can also see from discussions like these, when understood in light of comments such as those made by Julian Caddy about Brighton’s Palace Pier, that one’s investment in the local pier is about much more than just a nostalgia for ‘the good old days’ of British seaside culture, its about offering resistance to heavily classed politics of taste more broadly and about questioning regeneration trends that threaten to turn pockets of the seaside into palatable weekend destinations for the urban affluent.

- Baily, N. (2010) Understanding Community Empowerment in Urban Regeneration and Planning in England: Putting Policy and Practice in Context, Planning Practice & Research, 25(3), 317–332.

- The Community Shares Co (n.d.) URL: http://communityshares.co.uk/hastings-pier-charity/ [accessed 15.3.16]

- Griffiths, R. (1993) The politics of cultural policy in urban regeneration strategies. Policy and Politics, 21(1) (1993), 39-46.

- Miles, S & Paddison, R. (2005) Introduction: The Rise and Rise of Culture-led Urban Regeneration, Urban Studies, 42 (5/6), 833–839.

- Newman, A & McLean, F. (1998) Heritage builds communities: The application of heritage resources to the problems of social exclusion, International Journal of Heritage Studies, 4(3-4), 143-153.

- Roberts, L and cohen, S. (2014) ‘Unauthorising popular music heritage’. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 20(3), 241-261.

- Smith, M.K. (2004) Seeing a New Side to Seasides: Culturally Regenerating the English Seaside Town, Int. Journal of Tourism Research. 6, 17–28.